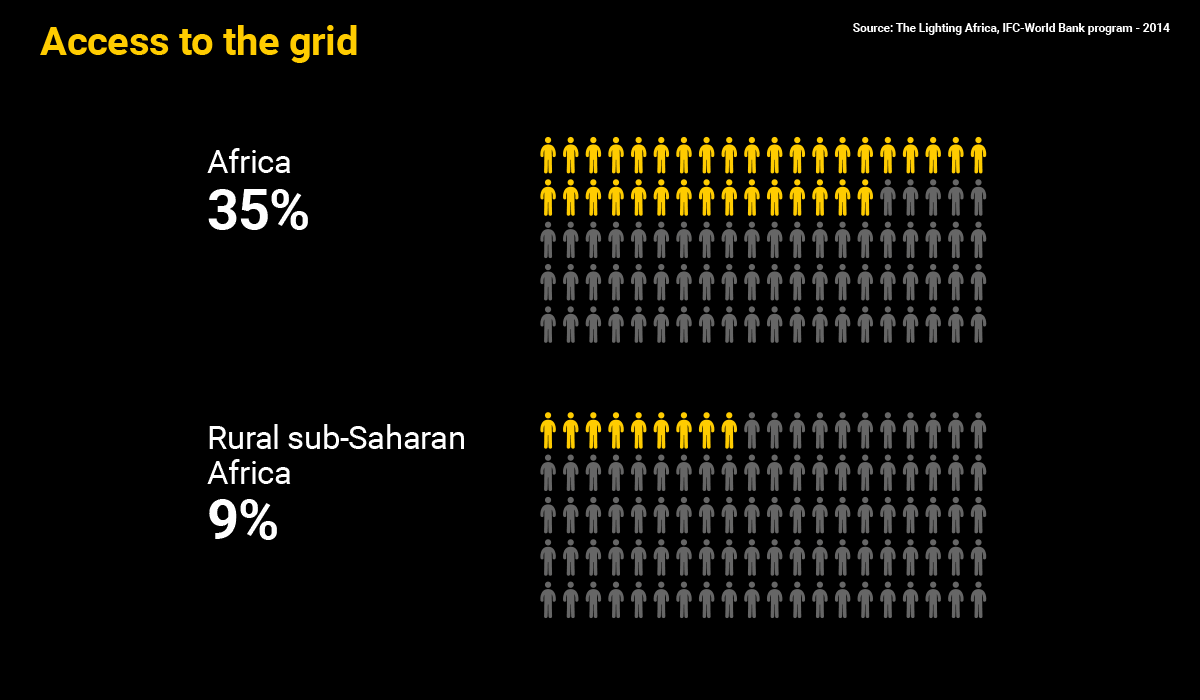

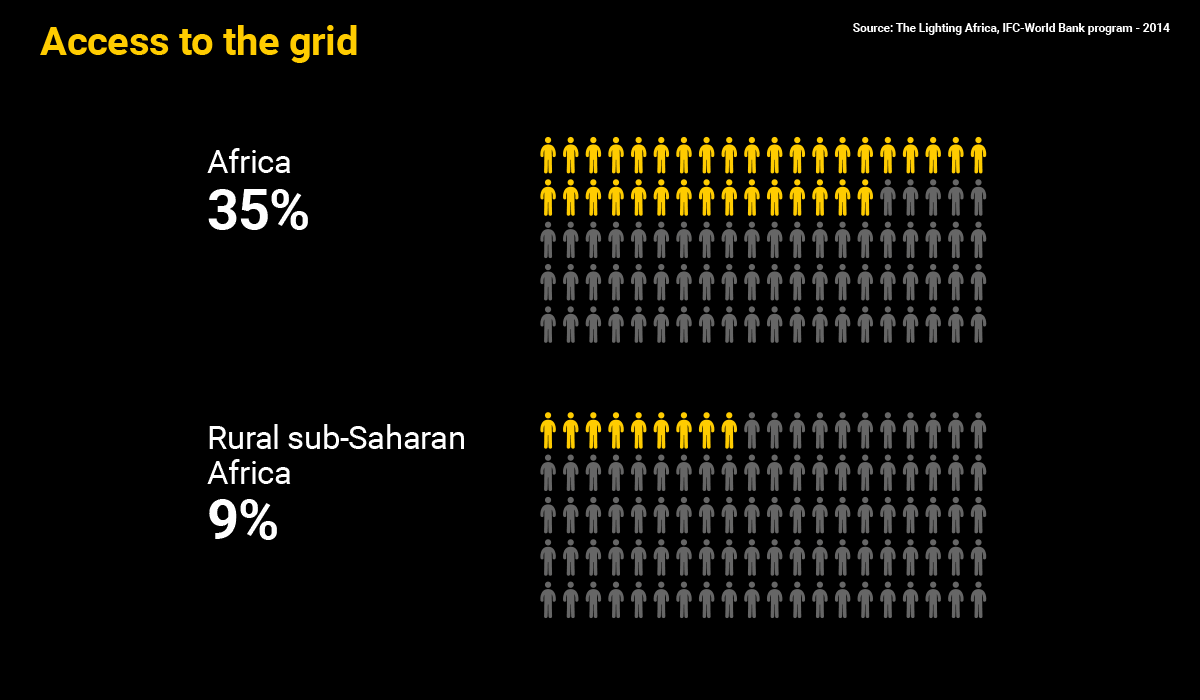

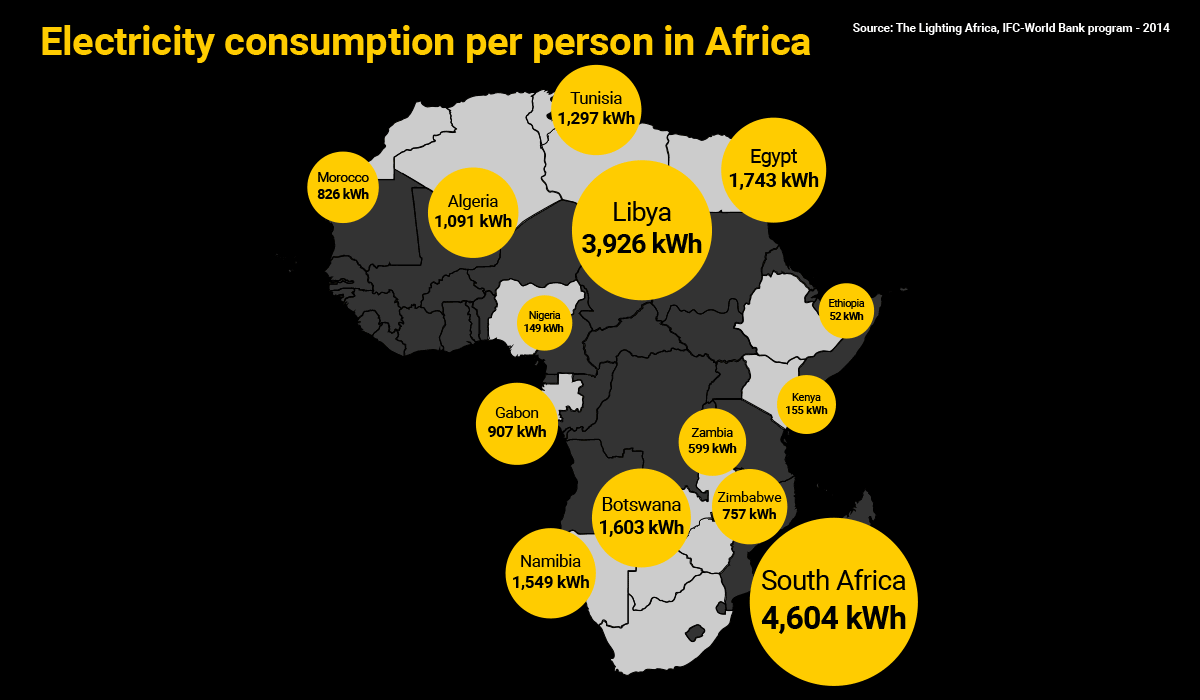

The lack of electricity is a key factor in Africa's social and economic underdevelopment. Production costs are higher in African countries than in other parts of the world, thus affecting their competitiveness in global markets. As a result, the region is the epicentre of the global energy crisis.

There is, however, one resource that Africa has in abundance: sunshine. Most of the sunniest places on the planet are found there and the average solar radiation levels in African countries are higher than in other continents.

This places solar energy at the centre of the debate, because it is a viable way to bring energy to almost any place without having to invest in big infrastructure.

An investigation began 10 years ago to take a serious look at the possibility of developing home solar energy systems. The Lighting Africa programme, sponsored by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the World Bank, began to encourage financial institutions to boost the use of solar energy by rural consumers.

In 2006, the price of a home solar energy system was about $500, an affordable solution for certain segments of the population, but still out of reach for those at the bottom of the ladder.

After the arrival of the first companies dedicated to the design and importation of solar energy systems, a search began for real solutions. First, battery capacity was reduced so that a smaller battery could be used without a converter.

The price of equipment was reduced in this way, meaning that poorer people could afford it. "We facilitate business between the market and manufacturers," explains Itotia Njagi, programme manager for Lighting Africa, an organisation that also works together with the governments of countries such as Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Rwanda and Uganda.

Itotia Njagi, Manager of Lighting Africa. Lighting Africa is a facilitator: it promotes business between markets and new manufacturers to integrate solar energy in isolated areas. In Africa, it collaborates with the private sector, but also with governments of different countries.

Initially, our goal was to encourage financial institutions to extend loans for solar products that ten years ago cost about $500. This was a solution for certain social segments, but it did not reach the base of the social pyramid. In 2006, some manufacturers with local experience started to arrive and they reduced the battery capacity, achieving a smaller battery that did not need a converter. This way, prices dropped and it was possible to reach the base of the pyramid.

Kenya is the fastest growing market and 21 out of 45 manufacturers, although produced in China or India, are based here. Kenya has become the regional hub. However, we are seeing strong growth across Africa because the technology prices are reducing. Five years ago, one watt cost two dollars. Now, a quality solar panel costs less than one. Battery technology is getting better, products last longer, and systems are becoming more efficient. Consumers are realizing they no longer need 200w systems; now, they can use some appliances with 30w.

The challenge in Africa isn't providing affordability, but providing a system that allows consumers to pay for products in small instalments, equivalent to the daily spending of kerosene over a period of time. The Pay-As-You-Go prepayment system has meant an innovation in funding and has managed to provide a product with an instalment similar to the daily cost of kerosene. I would say Pay-As-You-Go has addressed one of the major challenges regarding market development.

M-Kopa, born in Kenya, is not only a Pay-As-You-Go prepaid system, but also added the Plug-And-Play concept, based on simplicity of use: it does not need to be installed for a professional, or to set up devices. Once the system is connected, it starts to work. M-Kopa also reduced the size of the 200w battery to 10w, and created a 30W home solar system that costs $150, about the same amount a family pays for one year's kerosene supplies. It is an innovation that works via mobile phone platforms, but what we're seeing is only the tip of the iceberg. This just started.

The market is heterogeneous, it has different segments. M-Pesa is directed to an important part of the market that has no access to microfinance institutions. I would say that Mobile Money and Pay-As-You-Go system are not a prerequisite for solar energy, but since its introduction two years ago, we have seen a market growth of over 150%.

Solar energy is more widespread in the eastern countries thanks to the further development of Mobile Money and an attractive regulatory environment. In most eastern countries the sector does not pay taxes, while in the west taxes are between 22% and 33%. The silver lining is that western governments have realized that and countries assembled in the ECOWAS, 16 in total, ar in the process of reducing taxes, which will eventually open the market. Financially speaking, microfinance institutions in east Africa are quite sophisticated and have extensive rural penetration, unlike western countries.

We are not debating about which system is better. Obviously, grid power provides much more power than solar panels. However, expansion of the network is very slow, so millions of people would have to wait 20 or 30 years to be connected. Even if the connection was made in the next few years, solar energy could reduce the gap during this period. We do not know how solar technology and appliances will be in 20 years. Maybe 30w or 40w systems, will be capable to provide the same amount of energy than regular networks. Solar efficiency is currently between 19% and 23%, but even up to 40% of solar energy received by the panels could turn into electricity. In 20 years, people may be still connected to the network or maybe solar energy will catch up. Our goal is to provide a better system in the present.

While lower prices and greater efficiency has played a key role, the main consolidator of solar energy access in economic terms has been the introduction of an innovative business model. Pay-as-you-go technology, based on prepaid top ups using a mobile money service, has provided a solution for microloan payments.

Pay-As-You-Go is a cheap, efficient and financeable service. But to ensure accessibility one thing is needed: simplicity. The Plug-and-play concept when using a product is based on simplicity as it doesn't need any configuration or a technician to install it.

The device is plugged in and begins to work. In the case of solar power systems, a panel goes on the roof and is connected to a battery via a cable. Lights or phones are then connected directly into the battery.

Although it might not seem that important, Njagi explains that "10 years ago there were not enough technicians to carry out these installations in Africa". Plug-and-play therefore was the last piece in the puzzle for solar energy systems to really take off in Africa.

Since 2009, the use of home solar systems has grown dramatically, with an annual sales growth of between 90 and 95 percent. Today, market penetration of solar lighting products has risen to four percent and the market is rapidly developing, thanks to the arrival of new manufacturers and suppliers.

Multinational companies like M-Kopa and Mobisol have intensified competition and are generating greater market coverage.

M-Kopa owes its success to the combination of several innovations. They reduced battery size from 200 watts to 30 watts, and thus brought the cost of a system down to $150, which is equivalent to a family's annual kerosene bill. In a nutshell, M-Kopa lets its customers pay in instalments for a system while it is being used. And all this is done through a simple SMS message.

Once established, the system was replicated by companies such as Mobisol, based in Tanzania, another country where mobile money usage is high. According to Robert Zeidler, the company's African head, the key to success hinges on the efficiency not only of their products, but the appliances used as well. "We promote the use of devices that work with DC [direct current] so that people make the most of electricity," he says.

Robert Zeidler, Regional Manager in Africa for Mobisol, a company that provides solar systems that can be paid with a mobile phone via Mobile Money.

Microfinance allows customers to purchase the system in monthly, weekly or daily instalments to pay off the solar system. Therefore, customers do not pay for energy but for the equipment. Once paid, the system belongs to the customer and the energy is free.

Yes, of course. There are two countries, Kenya and Tanzania, where M-Pesa is everywhere. We chose the eastern African market to start because this is where Mobile banking is really developed and everybody just uses it. In the Lighting Africa conference in Tanzania in 2010 we found our current local partner and decided to settle in the country. Currently, we have over 10,000 customers. In 2013, the first year, we sold 2,500 systems; in 2014, over 7200; and this year we expect to sell 30,000. Tanzania's average is 4.8 persons per family, so we have reached 50,000.

I think it is not possible to launch a company like Mobisol without a Mobile Money system, simply because it is not possible to collect the cash. In the case of Tanzania, and because of its size, it would be very difficult to collect, so the use of mobile banking is a huge savings. We are therefore focused on the market in east Africa, at the moment Tanzania, and with a pilot in Kenya. Rwanda is one of the new large markets, and even the government is taking Mobisol as an option for rural areas. We are also looking at countries such as Uganda or Zambia, where M-Pesa already exists, and others where Mobile Money is being introduced. It depends on the banking environment, but in the future we can think of them.

We don't want to sell systems that just provide lighting and mobile charging because we know energy demand will rise. When we offer the product, the first thing people ask is whether you can connect a TV. There is much more demand for energy, including rural households, so systems must provide more energy. We also want to promote the use of appliances that run on direct current (DC) so that people can benefit much more from the energy. And one of the problems is that people still have appliances that run on alternating current (AC), and this would require the use of converters. So we're trying to replace the AC with the DC and in some of our plans we are including a TV that works with DC as a gift.

We have added a service for businesses development. For example, a unit that can charge up to ten mobile phones at a time. In addition, we have developed a system for solar hairdressers through a hair-cutting device that works with DC current, for barbers in villages where there is no electrical connection. Therefore, you can buy a device for energy, but you can also use it to generate business.

Mobile banking is changing markets and we do not know where will it go. Expansion of service sales via Mobile Money is what we began to see, and it will keep on growing. Many businesses are already making a profit out of it, because they can secure their cash, while people can pay through mobile banking and increase market and business flexibility. I think this has greatly improved the business environment in general. The solar sector is well advanced, a well-known concept, and there is a natural use of mobile banking.

As well as supplying dwellings, Mobisol has launched products that generate new businesses, such as a DC hair clipper for hairdressers in areas without electricity. Mobisol's growth boils down to its knowledge of local needs.

This is exactly why solar power is more developed in East Africa than in West Africa or the centre of the continent. Until mobile money takes root in other African countries, it will be very difficult for firms like M-Kopa or Mobisol to flourish.

In addition, as is the case with mobile money, the solar energy sector also needs a competitive market. And though the sector is not taxed in most East African countries, the tax rate stands at between 22 and 33 percent in West Africa.

Meanwhile, West African businesses must deal with excessive costs that push up retail prices and have difficulties collecting fees without a consolidated mobile money payment service. One example of these companies is PEG in Ghana, which replicates the technology and the business model of M-KOPA and aims to reach 20,000 households in 2015 and 100,000 in 2016.

There is a small group of countries in southern Africa with other characteristics, due to the influence of South Africa, the economic powerhouse on the continent. Although very depopulated, countries such as Namibia or Botswana have significantly more robust economies, meaning that technological development is also governed by different rules.

In Namibia, for example, access to home solar energy systems does not depend on microloans granted by companies. "It is the state that provides loans for the purchase of solar energy systems," says Zivayi Chivugare, director of the Namibia Energy Institute.

Namibia has an electricity connection rate of 35 percent, close to the sub-Saharan average, but with a huge extension of territory containing only two million inhabitants. The government therefore also finances the electrification of public institutions such as schools, police stations and clinics, and installs mini-networks and power plants that supply communities from 1,000 to 2,000 people.

In this context, foundations such as Kayec or Young Africa train young people in how to install solar energy systems. These are more powerful and complex systems than those offered by companies such as M-Kopa, Mobisol or PEG Ghana, but have the same goal: supplying electricity to those without access to the network.

Solar energy is a real solution to the energy crisis in Africa. And even though the electricity network provides much more energy than what solar can generate with current technology, it could take 20 or 30 years to connect hundreds of millions of people to the grid.

"It is not about choosing a system," says Itotia Njagi. "Even if people were connected to the grid in the next two years, solar energy could reduce the gap right now." And the fact remains that despite the development seen in recent years, today, two out of three Africans will use kerosene.