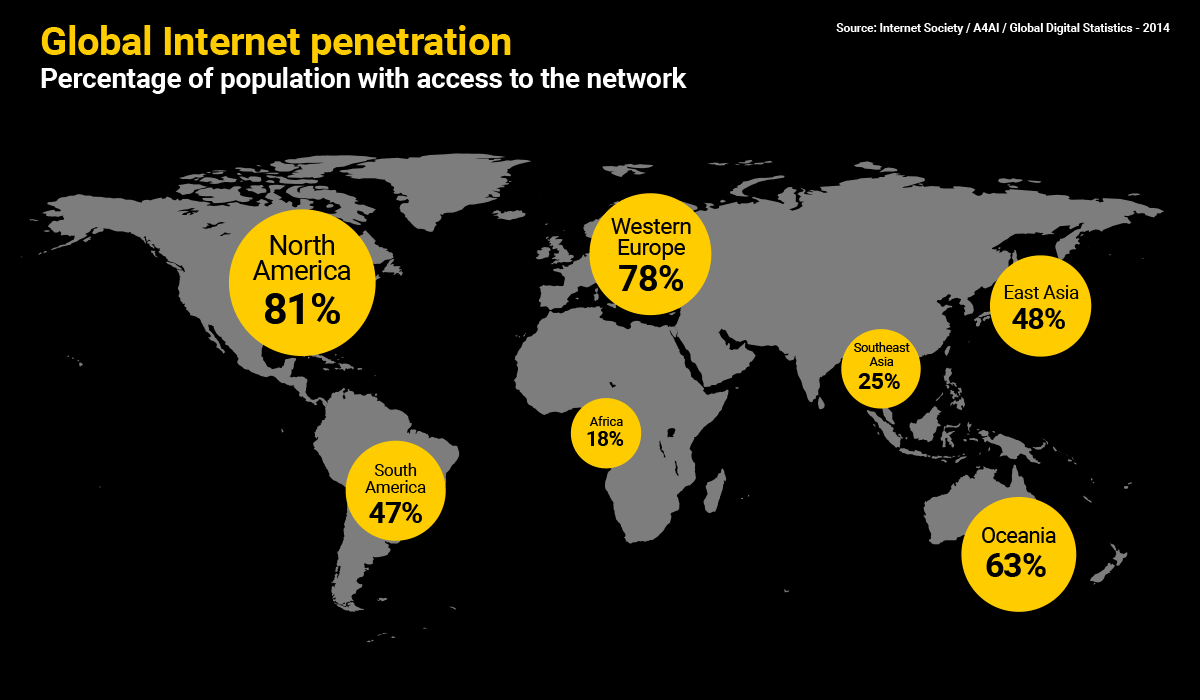

In sub-Saharan Africa, mobile technology has evolved rapidly, but this has not happened to internet access. With 170 million users, internet penetration in Africa is at 18 percent, which is significantly lower than the global average of 30 percent, and only one in 10 households is connected to the net.

Still, the number of connected users in the continent grew by seven times the global average between the years 2000 and 2012, according to Internet World Statistics.

"Africa has reached a penetration which has broken the barrier of 15 percent, and that's important," says Nii Quaynor, a scientist who has played an important role in the introduction and development of the internet throughout Africa. He is known as the "father of the internet" in the continent.

However, the ability to produce software, applications and tools is not developed enough because there's a lack of a critical mass that incorporates knowledge.

Most sub-Saharan countries produce very few professionals, and there are no technology investment strategies. "It is becoming increasingly difficult to help creating supplies, because the established companies are getting stronger and there may eventually be no space left," says Quaynor. The fact is that most countries focus on technology use and consumption, but not on production, which is what builds up the economy.

Nii Quaynor is the board chairman of the National Information Technology in Ghana, and director of the Internet Society in Ghana.

In the late 80s, when I returned from the United States, I began to see how to build networks for businesses, but with time the internet began to mature. In Ghana, there were no technical skills and I established a computer science department at the university. Between 1979 and 1988, I trained a lot of people and then formed a company to start mobilising the city engineers. The main challenge was to prepare the environment. Politics, businesses, economy, everything was new. At that time, the environment was not prepared. It yet isn't, but it has significantly improved.

Because we don't have a critical mass that incorporates knowledge. Most of the regulations are to encourage investment, but not development and growth. We have not had the opportunity to develop professional ethics; and if you look at the production of graduates, most countries produce very few. The base is to teach programming, but we are not properly teaching this in college or schools. In short, there are many challenges because it is a new discipline. So far, most of Africa focuses on technology use and consumption, but not on production, which is what builds an economy.

If you have a market that asks for supplies and produces absolutely nothing, your economy could be directed from outside. The immediate effect is that you do not decide your future in terms of knowledge to survive as an economy. In the rush to acquire knowledge and technology, we have focused on the aspect of use and not on building supplies, and this will become increasingly difficult, because the established companies will become stronger every day. And in the end, we may not find our space. So let's focus on supplies, because there may be things with which Africa can contribute to the world.

I've seen encouraging things in my experience of introducing internet here. The industry is changing but not quickly enough, because investments are going to other places instead of coming to Africa. We are making progress considering how we were two decades ago, but globally, the world is moving faster and the digital divide is increasing. But there are also encouraging things. In Ghana, the concept of openly providing information has been introduced, which is useful to create research and education networks. Now, universities can share facilities, laboratories, and libraries. We must take full advantage of the internet with the few resources we have, towards maximum development.

Many governments are behind infrastructure investments. This is something new. Before, governments wanted the private sector to take charge of it. But the mix between the private sector and the public is the winning bet. In some places, the private sector created the infrastructure and the government only used it, but the fact that the government is creating infrastructures itself is something that will help the entire industry. It is going in the right direction, with the commitment of both private and public sectors. There is a greater political commitment than before.

Africa has reached a level of internet penetration that has broken the barrier of 10 to 20 percent. When you get to 20 or 30 percent you're fine. I think the future will depend on the skills we are developing. Our ability to produce software, applications and tools is still undeveloped, and we cannot lose the opportunity to create them ourselves. The market is not mature enough yet, but I think that in the future, governments will have a greater role.

When you don't have enough opportunities, your vision becomes shortsighted and blurred, and interest in collaborating is practically nonexistent. The commitment of companies with internet is very limited in Africa, so we have to create a political environment that helps them focus on what is important to us, which is development. However, I believe very constructive things will come in the next five years.

Internet development in Africa has made great progress since the mid-1990s, and especially in the 2000s following changes in policies and regulations. Such changes have been achieved thanks to the effort of leaders like Nii Quaynor.

"The main challenge was to prepare the environment. Policies, business, economy, everything was new," says Quaynor.

Until 2009, the only way to connect to the world from sub-Saharan Africa were through satellite connections, which are very expensive and low in capacity. The new submarine connections led to a remarkable increase in data transmission capacity and drastically reduced the transmission time and cost.

Today, there are 16 submarine cables connecting Africa to America, Europe and Asia, and international connectivity is no longer a significant issue. This has allowed countries to share information, both within the continent and to the world, in a more direct way. It has created more space for innovation, research and education.

"Networks have ended the isolation of African scientists and researchers. You now have access to information from the more developed countries, and this is changing the way people think," says Meoli Kashorda, director of KENET (Kenya Education Network).

Meoli Kashorda, executive director of the National Research and Kenya Education Network (KENET), which aims to provide broadband connectivity between institutions of higher education and provide international broadband internet.

Until 2009, the only way to connect was via satellite, so for many years we were connected with the rest of the world in a very limited and very expensive way. Finally, in 2009, the first submarine cable was installed. Now, optical fiber submarine cables connect the countries that lie along the coast, both east and west. There are at least two cables from Djibouti to South Africa, and on the Atlantic there are wires that reach Europe. So the countries that lie along the coast are easy to interconnect.

We are also getting interconnection within Africa. However, countries that have no coast have more difficulties to connect, as they depend on other countries for access to fiber optic. Due to these difficulties, a connection from Kenya to Nigeria is still faster across London. But we hope that in the next two or three years we will have direct links between almost all African countries, as the fiber will be available to all.

Internet price in Africa has been high, in part because you have to connect through Europe. But when we began to interconnect between African countries and traffic began to flow, what happened was that prices fell. So we hope that in the future innovation, research and education increase. What the network has done is to stop the isolation of African scientists and researchers. Now we can get resources that are in Europe, USA, or Asia, from wherever we are in Africa, and this is changing the way we think.

Once international connectivity was resolved, connection prices fell; however, prices within the countries did not and remain very high, because we still need to build the infrastructure. Another big problem is energy stability, because for the connections to work properly you need to have clean energy, and the electricity in Africa is not stable.

It is up to governments and regional economic communities to implement policies that allow inland countries to benefit from the international connectivity. According to Kashorda, it will take a few years to achieve direct connection between all African countries.

The connection of Africa to the world is progressing, and so is the connection between African countries. There is, however, one final goal to meet, perhaps the most difficult: the interior connection within a country.

International connectivity deceased the cost of the internet. However, the lack of infrastructure in rural areas has not allowed for the same price reduction inside the countries. It seems that, in Africa, companies have a very limited commitment to the internet.

"When there aren't enough opportunities, vision is blurry and short sighted, and interest in collaborating is practically non-existent," explains internet expert Quaynor. "We must create a political environment which helps these multinational corporations to focus on what is important: region development."

In sub-Saharan Africa, governments have traditionally left infrastructure in the hands of the private sector. Recently, however, there seems to be a greater political commitment to this issue, and some governments are creating infrastructure, either on their own or in partnership with the private sector.

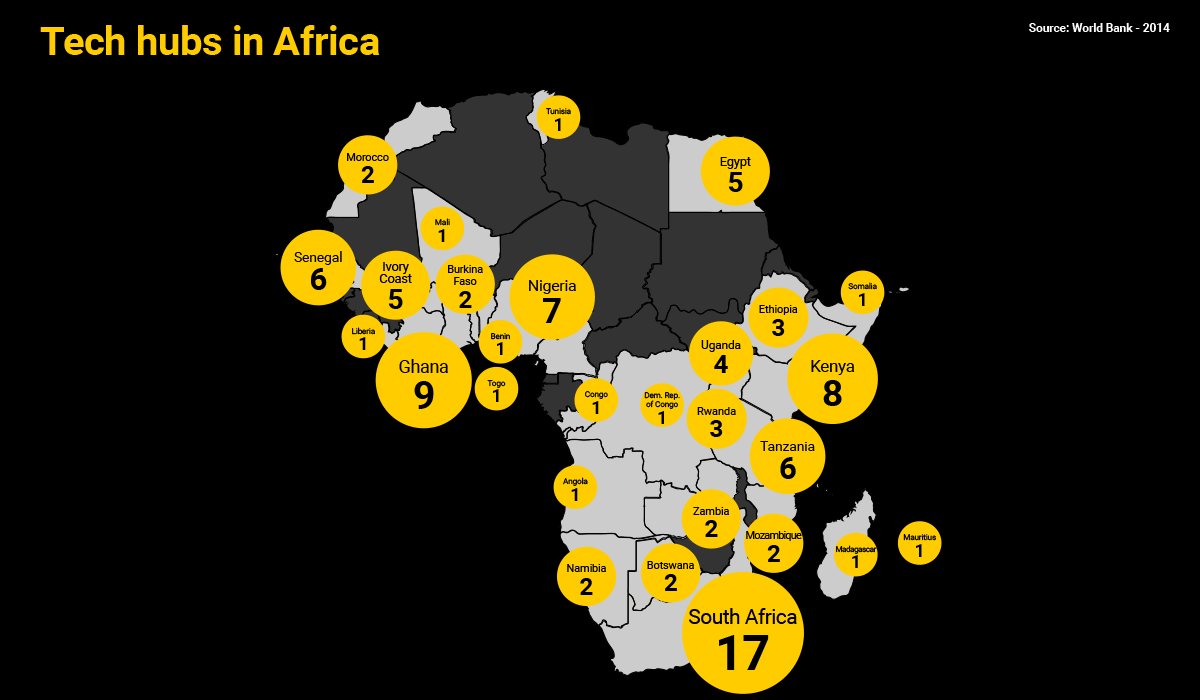

There is a real Pan-African movement of technological centres that is encouraging community building and empowering young developers to create innovative products and companies. There are now about 100 technological laboratories in 28 countries across Africa

Boubakar Barry, CEO of Wacren (West and Central African Research and Education Network).

It has improved since the mid-90s, but the greatest progress was in the 2000s, with the changes in regulations. Of course, we still have many challenges ahead, because penetration has occurred mainly in urban areas and in large cities but there are many areas that still do not have any access. International connectivity has increased in recent years and there are already many submarine cables. The problem now is the internal distribution of countries and connectivity of inland countries, which have no coast. Here's a great task for policymakers and regional communities, to implement regulations that allow inland, and not just coastal countries, to benefit from internet.

There is a direct relationship between internet penetration and development. And there will be a greater impact if educational institutions' connectivity improves. Access to internet resources is essential and it means economic development for countries. That is why we focus on how to improve connectivity in educational and research institutions. I think politicians are well aware of the importance of access to the network for socio-economic development, and an example is what is happening in the world of mobile phones in Africa. There are applications for communities and farmers who, through information, can draw maximum benefit by selling what they produce. Another example is Mobile Money; these are technologies developed in Africa to be used by people living in remote locations.

There are more and more young Africans developing applications according to local needs. Each new application or innovation is something extraordinary, and it looks like normal. It is development, evolution. This tendency exists and I do not expect it to backtrack. I am quite optimistic.

In the late 90's or early 2000s very few people had access to the network. But today Internet is in Africa. Although people do not have permanent connection, they are connected to each other via their mobile devices; it has become normal and necessary for their work and leisure, also in remote areas. Despite all this, the level of use is different than in developed countries, obviously due to price differentials, because it is still very expensive here. Prices are dropping, they will continue to drop, and internet consumption will increase. However, a lot still has to happen, to reach the level of development of other regions.

This trend is expanding at the speed of a new "hub" every two weeks. DTBI in Tanzania, CcHUb in Nigeria, RLab in South Africa or iHub in Kenya, are some of the most popular centres in Africa.

The great growth of these incubators throughout the continent is a consequence of internet development, which acts as an irrigation hose. Wherever the optical fibre cables are, new hubs grow like weeds and start to modify local ecosystems. But in those places they haven't reached, the land remains dry and does not produce anything.

In order to bring technology to low connectivity areas, several projects are being undertaken in different parts of the continent. One of them is Citizen Connect, created by the MyDigitalBridge Foundation, with support from Microsoft and the Communications Regulatory Authority of Namibia.

Citizen Connect seeks to provide the infrastructure needed to offer connectivity and services to citizens, regardless of their location and income or the existent infrastructure.

One pilot project is being carried out in Oshakati, a small town in northern Namibia. It uses a technology known as White Space, an innovation based on the use of blank spaces, or the non-use of the frequencies assigned to broadcasting services, to offer affordable high-speed internet connection in remote areas.

Africa is progressing towards greater connectivity, prices are falling slightly and internet use is increasing. Nonetheless, there are still some obstacles to expand access to mobile internet, such as affordability and investment in network coverage expansion. And while internet is already common in sub-Saharan urban centres, more than 70 percent of the population live in rural areas.