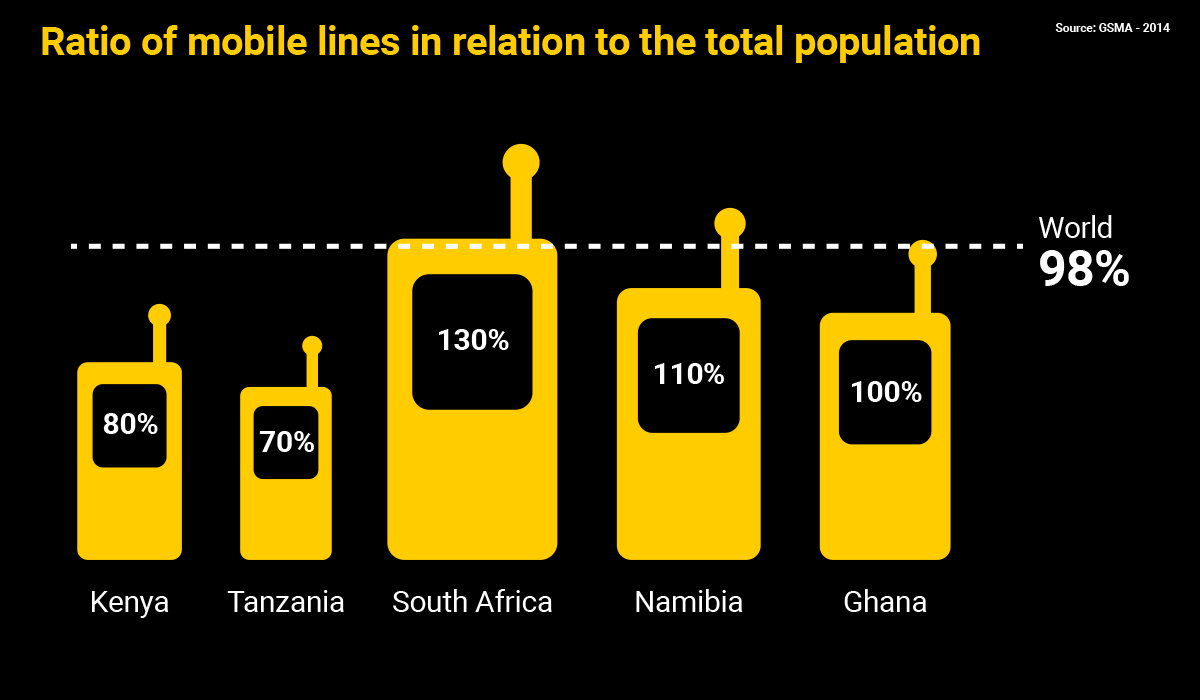

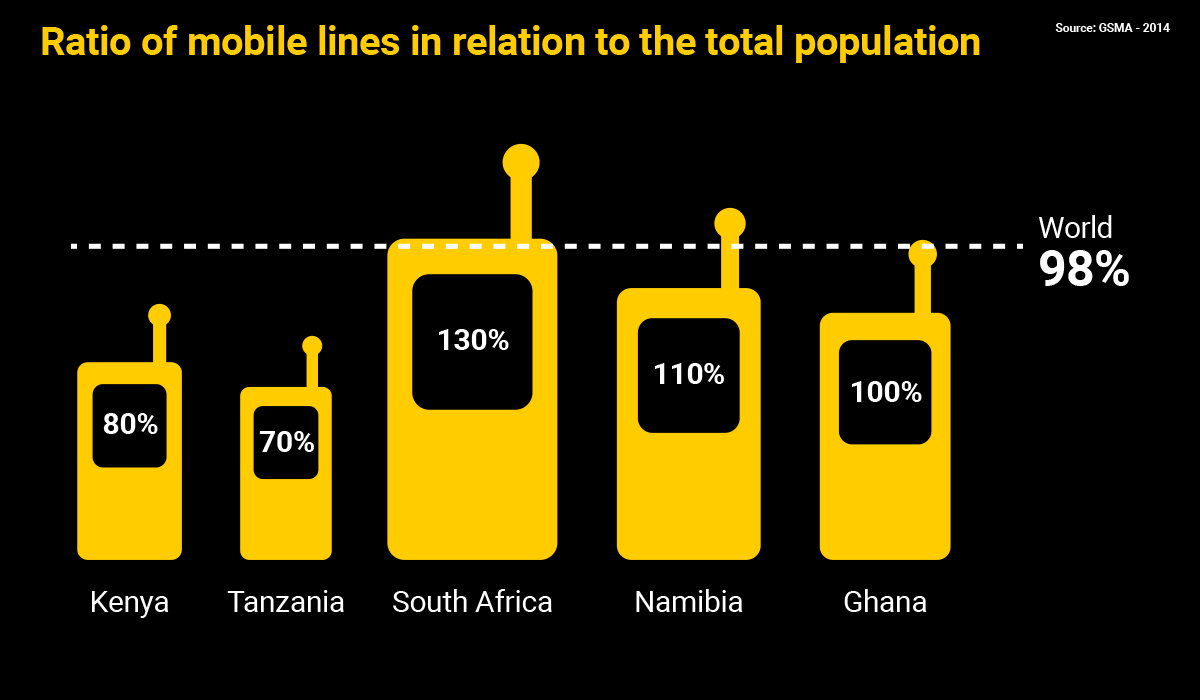

In Africa, many people lack access to electricity and running water but do own mobile phones. With more than 330 million unique subscribers, the mobile penetration rate in Africa is around 38 percent.

The number of new subscribers has grown at an annual rate of 18 percent in the last five years, while costs have gone down, reflecting greater competitiveness and affordability. However, the penetration rate in sub-Saharan Africa remains the lowest in the world, according to GSMA, the association of mobile operators worldwide. Technology's impact on the region, however, is undisputed.

A Q&A with Michael Nique, director of innovation at GSMA, the association of mobile operators worldwide.

We try to determine how mobile technologies, services and infrastructure could be used to improve access to basic services such as energy, water or sanitation. In Africa, specially in the east, mobile payments are de facto becoming a way to send money or to pay bills, and everyday more people depend on mobile technologies to pay for basic services. However, although mobile phones are widely used in cities and also in rural areas, most people don't have access to electricity or water.

The combination of M2M (machine-to-machine connectivity) and Mobile Money has allowed for the development of the Pay-As-You-Go payment system, which is based on pre-payment via recharges. This way, customers can pay for any services from the most remote areas with their phone. Therefore, M2M technology is being integrated to solar equipments or water pumps, and allows real-time information about those systems, such as the amount of solar energy reaching the batteries. With this, mobile phones transcend calls and texts messages and allow access to basic services.

Exponential growth of mobile phones, as well as the growth of Mobile Money services, is changing the economy in many markets. A large number of new jobs are being created in many countries where, once again, people lack basic infrastructure. This provides economic opportunities, because people can now access energy by using mobile technologies. At present, many people are benefiting from access to new basic services such as energy, but it could also be education, mobile banking or mobile agriculture.

We are witnessing a change, and now people are coming to Africa for different reasons than before. In the past, it was more about NGOs getting funds from developed countries and coming here to provide charity services. This distorts the market, since people don't appreciate it as much as if they are paying for services or products. The expansion of mobile phones and mobile payments are generating interest by the developed countries, because they realize they can create businesses in different parts of Africa and make profits. M-Kopa, for example, launched its business in 2012 in east Africa and has so far sold more than 120,000 solar home systems. This is a great financial and social impact.

It is a complex business, because this market is very difficult to reach in terms of distribution and perception, but there's also a real opportunity for those markets. I think it will change slowly. There are a lot of innovations in the large cities of Africa, so the question is how to take advantage of this talent and encourage growth of these start-ups. All in all, it's about having access to one's mobile phone and making the most of it. It's about understanding how these services and devices could have a higher penetration or impact.

Like in the rest of the world, the mobile phone emerged in Africa as a way to communicate via phone calls and text messages. But over time, the mobile phone became a technology platform that allowed the development of other services, thanks to cellular technology.

This is how Mobile Money, the greatest authentically African technological revolution, came into existence. Within less than a decade, this service has transformed the way people think about finance in Kenya, where it was created, and it continues to expand into other countries in Africa and elsewhere.

Instead of paying with cash, cheques or credit cards, customers can use their mobile phones to pay for any type of service. Mobile payments, especially in east Africa, are becoming the de facto form of payment, and growing numbers of people have come to depend on it.

This system has turned out to be particularly useful in countries where the majority of the population work in cities and send money back home to their families living in rural areas. Mobile payment is saving them time and money.

Johan de Lange, former executive vice president at Clickatell, a leading company in technological innovation and communication industry through the mobile.

When Safaricom launched M-Pesa in 2007, the cost per money remittance was very high and the lack of regulation had allowed experimentation. Operators, especially Safaricom, which virtually had the monopoly of the market, had to be linked to a bank to attract deposits, but there was no regulation. Kenya was an unregulated market, so the same market was who moulded the product. That was the reason for its success. However, what generated the service launching was the electoral violence in 2007, since the phones were the only way to send money to certain parts of the population. Thus, the need for an easier way to get money was created, and that accelerated the development of Mobile Money.

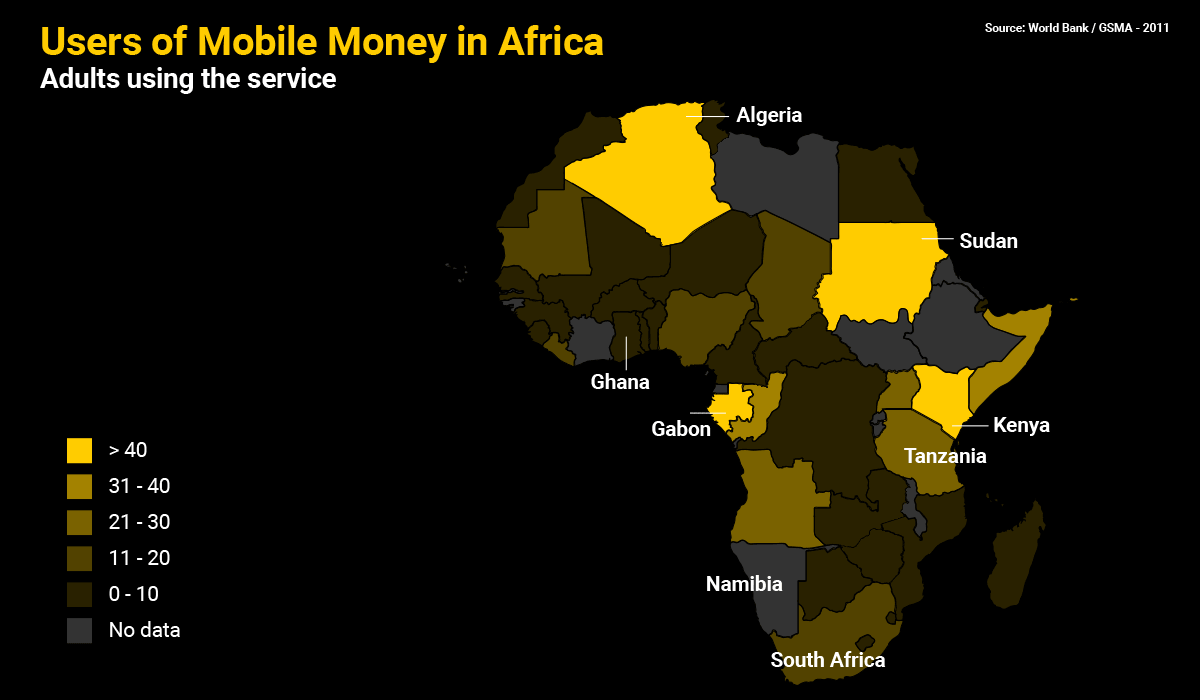

There are up to 40 million Mobile Money users in Africa, and 38 million of them are in the east, mostly in Kenia. Mobile Money has unique characteristics in east Africa. In the west, the process was more formal and central banks took control from the beginning, reducing the popularity of the product in some markets. This resulted in a much lower development of Mobile Money. In Nigeria, for example, when the Central Bank made its regulations in 2010-2011, it stated that banks would lead Mobile Money initiatives. Operators saw themselves relegated by banks.

You have to understand that the culture of banks is very different, very formal; it is an institution that was built around salaried and people with a certain purchasing power. But the goal of Mobile Money are people who only need a phone, regardless of their earnings. In fact, after introducing prepaid plans the service spread even more, and people quickly learned to reach others.

But traditionally, banks have not had an interest in this kind of clients, and the problem now is that southern and western countries depend on central banks. I think bank accounts are a too expensive service for this kind of people, since most Nigerians, for example, earn less than ten dollars per month. Is this attractive enough for a bank? I think the model has to be collaborative, between banks and operators.

It has changed over the last four years. I think this year we will see a larger expansion than in previous years, regarding Mobile Money initiatives. Banks will partner with operators and will therefore be more effective than in the past. But for now, mobile money operates around a bank and its customers to send money to the unbanked. It is mainly used by bank clients for remote payments, so it is basically to satisfy existing bank customers. We have to start building this together and get both parts to understand that they can both achieve their goals by working together. It is not a competition, this is not how it works.

M-Pesa, the fusion of the words "mobile" and "pesa", the Swahili word for money, is the biggest success story of the African technology industry. This innovation has provided financial services to millions of unbanked citizens, boosted economic growth and moved the equivalent of 25 percent of Kenya's GDP.

Created in 2007 by Vodafone for Safaricom, the largest mobile operator in Kenya, M-Pesa allows users to deposit money into an account stored in their phones. Once the money is deposited in cash at one of 40,000 agents, the customer can make transfers by SMS to other users or vendors.

Why did it start in Kenya? Because of the high cost of money transfers, the Safaricom monopoly and experimentation. "When M-Pesa was launched, Kenya's market was unregulated, meaning that the product was shaped by the same market. That is how it got to be so successful," says Johan de Lange, president of Mobile Transactional Services.

Unlike east Africa, the process in west Africa was much more formal because the central banks took control before the services emerged. This led to weaker development of mobile money. "For the time being, the east is spearheading innovation in Africa. The regulationist approach in the west will slowly change, however," says de Lange.

De Lange believes that banks will increasingly enter into partnerships with telecom companies to make the process more effective.

A good example of this development is the mobile money service provided by MTN telecom in Ghana, in collaboration with a number of banks. The service operates through authorised dealers who provide services on behalf of partner banks.

On top of technology like mobile money and SMS, one can find new innovations such as M2M, a system that lets you transfer data between machines. The combination of all three has resulted in the development of the Pay-as-you-go option which involves making pre-payments by topping up credit. In this way, it is now possible to pay for any type of service from the most remote areas with just a mobile phone, thanks to mobile money.

In the past two years, a large number of companies have been integrating M2M technology into their domestic solar energy systems and water pumps. Companies like M-KOPA and Mobisol owe their existence to mobile money payment systems. Their solutions enable people who lack access to electrical grids to pay for solar energy in small daily instalments.

This technological revolution is now also helping people working in agriculture.

M-Agriculture collects data such as market prices, farming techniques or weather conditions and sends them to farmers by text or voice messages. The start-up aims to combat the lack of information available to farmers when negotiating prices with intermediaries, a situation which causes huge losses to rural communities.

Farmerline offers services to fish farmers on the outskirts of Kumasi, Ghana's second-largest city. Over the last year and a half, the startup provided daily information on how much feed to give fish.

"This has allowed for more fishing and larger catches increasing their income," says Alloysius Attah, CEO of Farmerline. Although M-Agriculture is an emerging concept, the experience of companies like Farmerline or Esoko suggests that these applications can transform rural areas in the long term.

Despite the benefits of technological innovation, introducing a new product or service into rural areas with high rates of illiteracy is very difficult. In the rural communities of Ghana, 60 percent of people have mobiles, but only 10 percent use text. Voice is still the most widely used form of communication. New services therefore have to be very easy to use.

El galés Mark Davies, owner and director of the Esoko M-Agriculture Company is one of the leading technology entrepreneurs in Ghana.

Esoko is a communication platform for small farmers in Africa, which aims to help them increase their yields and profits. We specifically do two things: on one hand, we provide information such as weather forecasts or market prices, and on the other hand we offer a software platform to companies or foundations that hire our services, so that they can send their own messages to small farmers. The services operates through a platform that includes automatic and customized SMS alerts.

Agricultural industry is really complex, and all actors intervening in the value chain try to control the information. Africa, however, is one of the information products' frontiers. Although in large cities there is access to smartphones and the net, in rural areas there is a significant lack of technology. If, to this, we add illiteracy, it becomes extremely hard to bring information to this communities. This is why our business is based on extending mobile technology across Africa.

Mobile phones are still a product and a voice service in rural communities in Africa. In Ghana, I believe 60% of small farmers have mobile phones, but only 10% of them send text messages. Therefore, introducing a product, service or technology is complicated. Communities have many needs, but we must try to really understand them, one has to be more of a sociologist rather than a technologist. If we are going to implement innovations in a rather conservative community, we have to do it alongside its members. One must know who their leaders are and how are they using technology. One must focus on the community's needs.

Generally farmers are at a disadvantage: there is an asymmetry of information between uninformed producers and intermediaries, who are aware of the prices and usually have more power. Indeed, some producers specifically require written messages, so they can use them as evidence. We have recorded a 15% improvement on the farmers' annual income. However, we have stories of farmers who sell up to 500% more by choosing a different market or operator.

We are currently in seven countries, but in the coming years we will reach 14. Our direct customers are organizations representing farmers. We have about 40 partnerships, projects or businesses that work with us and represent about 50,000 or 60,000 farmers in Ghana. If we take into account all the countries where we are located, we assist up to 400,000 farmers. We think there will be a turning point regarding product domain, so we expect to reach three million farmers by 2020. We are a private company with a monetary target, yet we also aim to generate change on Africa's agricultural market development.

It's fantastic, there are many opportunities in terms of development. Still, the ICT industry in Africa is still very young for technology entrepreneurship, the level of expertise is low and there is almost no competition. Ghana, for example, has a very small IT community, it is a no man's land, and one of the reasons for that is the lack of venture capital to allow entrepreneurs to pursue their projects. Still, the emergence of new technologies and services from previous innovations is exponentially multiplying the number of business opportunities.

This is turning Africa into an attractive continent and, in recent years, many investors from developed countries are coming here to innovate. What is exceptional about Africa is that here, innovation generates a much greater impact.The difference can be a family being finally able to send their children to school.

Africa remains the poorest region in the world and the ICT industry is still very young, with little experience and competence. "Ghana has a very small IT community. It is no man's land," says Mark Davies, director of Esoko. However, the emergence of new technologies is multiplying the number of business opportunities.

Africa is becoming an attractive continent and in recent years a lot of investors are coming to develop new ventures.

Enterprises seek to create new services, but on one condition: they have to be developed for mobile, the only device most Africans have access to. Despite progress in the industry in recent years, the greatest impact is yet to come. Two-thirds of the population still do not have mobiles.