DROWNING MEGACITIES

Text and Media by

Lasse Wamsler, Sune Gudmundsson and Sven Johannesen

Design by

Mohsin Ali

1

on the front lines of the African climate battle

The world is getting warmer, the rain is growing heavier and the oceans are rising. At the same time, the world’s rural inhabitants are migrating to its cities on a massive scale.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the part of the world most affected by the dual pressure of climate change and the rapid, uncontrolled transformation of its cities into megacities.

The extreme speed and scale of urbanisation has swallowed up many former peasants, incorporating them into the vast slums of sprawling megacities.

In these unplanned, hostile urban environments, where infrastructure is at a minimum, they are exposed to the dangers posed by rising seas and heavy rains - forces that wreak havoc and cause deaths every year.

But, from Lagos in the west to Dar es Salaam in the east, slum-dwellers, the middle class, and the elite alike are fighting back against the waters.

This is a visit to the front line of their battle: to Africa’s drowning megacities.

The African megacities are under dual pressure from uncontrolled urbanisation and floods worsened by climate change. The result is a catastrophe that is unravelling in slow motion and threatening the livelihoods of millions of people.

Karogoli Elias awoke to the exact same sound he had fallen asleep to: the monotonous drumming of heavy rain on the tin roof of the shack he shares with his wife and children in the Jangwani slum.

In drought-affected areas, it is a sound that carries with it the promise of survival. But, in Jangwani, it spelled disaster.

The millions of tiny droplets turned into puddles, which then turned into streams and lakes. Within a few hours, the drops were transformed into a sea that began to disfigure the fragile, makeshift slum dwellings.

At first, the residents of Jangwani fought to keep the water from flooding their shops and houses. But soon, they had no option but to surrender and flee the rising waters.

“If I had known that Jangwani would be flooded I would never have settled here in the first place,” says Elias.

Karogoli Elias

DAR ES SALAAM, TANZANIA

Urbanisation

Located at the base of one of Dar es Salaam’s many valleys, Jangwani was one of the areas hit the hardest by the massive protracted floods that killed more than 40 people and displaced another 10,000 at the beginning of 2012.

Elias, his wife and their six children were one of 650 families resettled by the authorities on a hilltop on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city. More than three years later, the family still lives in the same tent that was meant to provide only temporary shelter. If the many ragged grey tents on the hill are anything to go by, Elias’ family is far from alone in its plight.

When the torrential rain hit Jangwani, it not only ravaged Elias’ home, but also destroyed his livelihood. In 1998, the tall Tanzanian had moved from the country’s rural west to eastern Dar es Salaam in search of a job. He eventually found employment as a security guard in the inner city. However, the resettlement meant he had to relocate more than 30km away. The cost of transportation alone exceeded his entire salary, so he had to quit his job.

Karogoli Elias is just one among millions of Africans who travel every year from the countryside to urban areas in search of a brighter future. As the least urbanised continent, Africa is currently experiencing a mass rural-urban migration. Combined with the fact that Africa is host to the world’s greatest population growth, the population of African cities is expected to triple from around 400 million today to 1.2 billion by 2050.

The population of Dar es Salaam alone is projected to increase more than fivefold by 2050 – from four million to 21 million people.

At the same time, on the west coast, the population of the biggest city in Sub-Saharan Africa, Lagos, is expected to explode from 21 million to 39 million inhabitants.

To put this in context by way of a comparison: During the last century, the population of New York has grown by a mere four million people.

This mass migration from the clay huts of the countryside to the tin-roofed shacks in the urban centre is happening so rapidly that it is impossible for the urban infrastructure to keep pace with it. Consequently, most newcomers end up in urban slums like Jangwani, with minimal protection against the effects of climate change.

Many of the slums are located in low-lying areas, with no drainage or sewage systems in place. This makes them vulnerable to tropical rain, which of late – due to the effects of climate change – is falling harder and for a longer duration than ever before. Eating away at the shoreline, the rising sea level represents yet another challenge for coastal cities.

Uncontrolled urban growth, combined with the effects of climate change, has left coastal African cities exposed to a slow-motion disaster. The scope of this disaster depends on the ability of the world community to mitigate global warming, and also on the ability of megacities to build resilience against a more extreme and unpredictable future climate.

While the world’s heads of state will gather in Paris in December to negotiate a common path to a more climate-friendly future, exposed coastal cities are already undertaking various ambitious experiments. Megacities, like Lagos and Dar es Salaam, have long ago initiated a counter-offensive against the water that attacks them from both sky and sea.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), climate change will cause a sea-level rise of up to one metre before the year 2100. For a megacity like Lagos, which lies partly at sea level and is partly built on a swamp, even a small rise in the Atlantic Ocean can trigger severe floods.

The war is fought on very different front lines: from slum-dwellers hoisting their furniture up towards the ceiling when water floods their living rooms, to billionaires constructing a brand-new peninsula from the ocean floor to protect the megacity from the attacking waves.

Yet, a large group are left as bystanders to the changing habits of the weather. Karogoli Elias used to have a job, but now his family depends on charity for survival while facing an uncertain future on a hilltop on the periphery of Dar es Salaam.

"The only good thing to say about my new home is that we are free from the floods," he says.

Invisible SLUMS

2

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Salim Mtepetallah has sent his wife and newborn daughter to safety outside the city, away from their home in the slums of Tandale. During the rainy season, Tandale is not a safe place for infants.

“When the rain stops, diseases emerge, and even though our house is spared from flooding, it has great consequences for my relatives and neighbours,” says Mtepetallah.

Three weeks after the last drop of water fell from the sky, large parts of the slum remain flooded. Hundreds of newly-hatched mosquitoes hover over the calm water, forming a living membrane. These mosquitoes are not only a buzzing inconvenience; they are carriers of malaria.

Faced with the problem of floods and the devastation and death likely to follow, Mtepetallah and other residents of his neighbourhood are fighting the water with a surprising choice of weapon: a simple GPS.

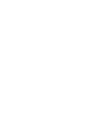

Even though Tandale has around 55,000 inhabitants, hundreds of stores and an ingenious system of paths and roads, the ward only exists as contour lines on official maps of Dar es Salaam. Like most of the city, Tandale has not been built based on a meticulous plan, but has come about haphazardly.

The neighbourhood is built on both sides of a river in a low-lying part of the city. Due to the lack of urban planning, Tandale has no sufficient drainage. The non-existence of refuse collection ensures that the river is clogged with rubbish, which prevents water from flowing during the rainy seasons. As a result, Tandale suffers from floods.

Houses and valuables are destroyed, and local business is in a state of paralysis. The rainwater mixes with sewage from the overflowing latrines, bringing a germ-infested fluid into homes and shops. When the water level finally subsides, residents are left to deal with diseases and infections.

Armed with a GPS, a pencil and a clipboard, Mtepetallah and other residents walk through their neighbourhood to record the exact locations of the roads, schools, shops, and houses built by the slum-dwellers. They also make a record of the locations most greatly impacted by the floods. By using drones to measure the topography of the area, the mappers can also predict where the water will accumulate when there is heavy rain.

The project is called Ramani Huria and the work on the ground is carried out by the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team with the help from locals and university students.The purpose of the project, which is organised and supported by the World Bank, is to map the Dar es Salaam neighbourhoods most vulnerable to flooding

Never before has the city been mapped with such precision. And these maps will constitute the foundation for the city’s emergency plan for future floods. In theory, these maps should enable predictions to be made about which areas will be most severely impacted by flash-flooding and when to warn and evacuate citizens. The end goal is to address and alter the situation of ruined habitations and fatalities caused by recurrent floods.

While the people of Tandale wait for improvements, individual households are preparing for the next rainfall. In the absence of central planning, the slum-dwellers are reliant on home-fashioned remedies to protect their homes from the water.

This has led the community into an arms race of sorts, where the residents compete by building their shacks on the tallest foundations possible - in effect, forwarding the water to their neighbours. Mohamed Issa Mbwana invested his savings thus, in order to be able to stay dry in his house when the rain falls.

Another Tandale resident – Ali Kijaji Ramadhani – is applying a DIY system, aiming to use a rope to hoist up and suspend his furniture near the ceiling when the water comes pouring into his living room.

However, what remains to be seen is whether the map that Salim Mtepetallah is struggling to finish will lead to a safer future for the slum. Ultimately, this will depend on whether the municipality uses the new detailed maps to provide the community with much-needed drainage by way of renovation and sewage systems.

Mtepetallah is optimistic about the future and is looking forward to the end of the rainy season and the return of his wife and baby.

“In five years, Tandale will no longer be flooded,” he says.

A large part of Dar es Salaam’s rapidly expanding slums do not exist on official maps. This makes it difficult to provide help when extreme amounts of water wreak havoc during the rainy seasons. As a first step towards a safer future, slum-dwellers are now mapping their neighbourhoods.

Dar es Salaam

Salim Mtepetallah

maps

Map Comparison

Salim's Map

Google Maps

Map showing parts of Dar es Salaam from a drone perspective.

Dar es Salaam is one of Africa’s fastest growing cities.

• The city has about 4 million inhabitants, a number that is expected to skyrocket to 21 million within 40 years.

• 7 out of 10 people in Dar es Salaam live in slums.

• The coastal city struggles with severe flash floods in rainy seasons. Some scientists predict climate change likely will bring increased and heavier rainfall to Dar es Salaam. Moreover, Dar es Salaam has been identified as one of the largest coastal cities in Africa highly at risk of sea-level rise and storm surges.

Dar es Salaam

Lagos, Nigeria

A bustling Nollywood industry and its whopping number of dollar millionaires have made the Nigerian powerhouse, Lagos, well-known. What is less well-known is that few other places are as heavily affected by the combination of rapid urbanisation and the effects of climate change. These days, the megacity is confronted by a dilemma: whether to defend itself from the ocean's surge and heavy rain, or to see the water as an integral part of the city.

Lagos spreads over some small islands, sandbanks and mangrove swamps around a lagoon along the Atlantic coast. Three-thousand people migrate into the city every day, while heavy rains and rising seas eat into the coastline, leaving roads and buildings flooded.

At the moment, Nigerian tycoons are busy building an artificial peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean - one that will protect a cosmopolitan elite from the unruly waters. But a few kilometres away, in Nigeria’s oldest slum, Makoko, people live as they always have: with the water.

Often called the ‘Venice of slums’, Makoko is a city-on-stilts in the belly of the murky Lagos lagoon. Twenty-three-year-old Gabriel Ayorinde was born here. Instead of playing football, he learned early on how to paddle a canoe, a favourite form of local transport that is also used as a taxi service and for floating DJing.

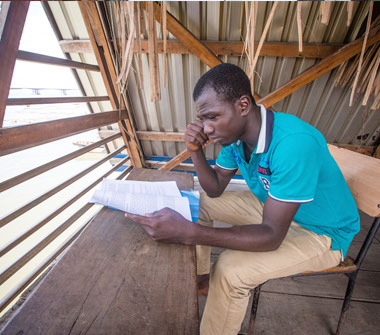

Sitting placidly on the second floor of the Makoko Floating School, Gabriel Ayorinde is preparing to attend university outside the slum.

“I come here to unwind from the noise and disturbances at home,” he says.

While poor Lagosians live on the water in Makoko, the ‘Venice of slums’, the Lagosian elite is constructing an exclusive new peninsula, rising from the Atlantic Ocean like a veritable reverse Atlantis. Eko Atlantic City aims to keep out both the water and the poor. It is, say critics, a form of ‘climate apartheid.

When Ayorinde momentarily lifts his eyes from his books, he can contemplate the lagoon, where a labyrinthine town of dilapidated wooden shacks sits on stilts around him. It is home to roughly 100,000 residents.

It is a maritime slum village, encircled by modern-day Lagos. The Third Mainland Bridge, the longest in Africa, rises 10 metres above the lagoon. Above the highway bridge hang high-tension power lines, piercing through the smog that feeds on the fumes seeping from Makoko’s countless fish-smoking furnaces. The power lines run right above it, but the community remains off the grid.

Electricity is rare within the community, as are other basic amenities, like clean water and sanitation. The lagoon works as both a refuse chute and a latrine - the grimy brown water full of plastic waste and a source of vector-borne diseases, such as malaria.

Regarding the community as a germ-laden hindrance to modernisation atop a monetisable waterfront site, the Lagos authorities have tried to evict residents on more than one occasion. Three years ago, they managed to forcibly evict 3,000 of the neighbourhood’s residents. During the eviction, the police killed a local chief.

Around the time a Nigerian-Dutch architectural firm constructed the Makoko Floating School, political sentiment has turned in favour of the over-water slum. The school is a triangular wooden structure rising from the foul-smelling waters as an example of modern, resilient design made of cheap materials, even as it embodies respect and deference for the community’s 100 years of adaptation to a life on water.

In recent years, the Lagos authorities have begun stressing conservation rather than eviction, perhaps because the Makoko Floating School has gained international recognition at exhibitions around the world. The school provides a welcoming refuge in which Gabriel Ayorinde can do his homework. Today, with the whole floor at his disposal, he feels pleased with life in the neighbourhood, despite its tarnished reputation - particularly because Makoko has managed to avoid the flooding and sea-level rise exacerbated by climate change and repeatedly affecting the rest of Lagos.

“It is only the residents inside the city who get flooded,” he explains, pointing at the high-rise buildings towering above central Lagos.

Despite being stricken by poverty and disease, the intricate water world of Makoko can still inspire megacities around the world as an example of in-built urban resilience, claims Swizz architect Fabienne Hoelzel. She is cooperating with Makoko residents to construct a refuse-driven power station in the area.

“For years, city authorities have discussed strategies to guard cities from the water. But now, people are starting to work on how to cope with water,” posits Hoelzel. “In Makoko, residents have lived with the water for many years, and I do believe many people can learn from their experience when discussing how to adapt to the effects of climate change.”

Makoko Floating School

Though an example of resilience for some, Makoko represents just a tiny sliver of Lagos, a megacity bordering a rising and ever more aggressive Atlantic Ocean that is causing erosion and flooding along its coast. Threats from tidal changes have led investors to set up a bold plan: the erection of a new peninsula, Eko Atlantic City, emerging from the Atlantic Ocean like a reverse Atlantis. The biggest building project in Africa, it is planned as an exclusive city and financial hub catering to the international and local elite.

In 2008, investors started constructing the peninsula out of millions of tonnes of sand dredged from the Atlantic seabed. The following year, construction commenced on The Great Seawall of Lagos, an eight kilometre-long seawall intended to protect Eko Atlantic City and the up-market Lagos district of Victoria Island from the frothing ocean. Today, workers busily lay the foundation for the skyscrapers that will fill up the peninsula in years to come.

“Eko Atlantic City provides safety for those that can afford it, but it does not remove the problem with erosion. Instead it transmits the problem down the coast to communities like Alpha Beach, whose homes and infrastructure get flooded over by the sea. It is a catastrophe,” argues Nnimmo Bassey, a renowned Nigerian environmental activist, author and director of the think-tank Health of Mother Earth Foundation.

Eko Atlantic City rejects the claim that the unusual entrepreneurial project has increased erosion and flooding in neighbouring communities. The investor group refers to the fact that the project has gone through a series of legal environmental studies and has been approved by the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Environment.

Today, humming activity fills the four-square-mile artificial peninsula as the first phase in the erection of the new city gets under way. In front of noisy cranes and construction machines stands Ibiene Ogolo. She is the developer of the Eko Atlantic City’s new marina.

The construction of Eko Atlantic City follows international best practice with its own sewage system and power supply, she explains.

And an important element of the sales pitch is the fact that the city will protect its new inhabitants from ocean surges, which are expected to increase as a consequence of climate change. The long seawall will allegedly withstand even the most extreme waves, and enormous drains will lead the rainwater away. The end goal is to create a city “made for the 21st century” in which cosmopolitan jet-setters can “work, play, live and invest”.

“Some people compare Eko Atlantic City to Dubai because of our marina. Others compare us to the Champs-Élysées in Paris because of our wide boulevards. Yet, others compare us to Manhattan or downtown Los Angeles because of their financial districts,” says Ogolo.

Supporters of the new city stress that it has the potential to become a hub for growth, creating much-needed jobs and revenue, and thus benefitting greater Lagos. However, in a city where seven out of every 10 people live in slums, it has inevitably sparked controversy. Since the city is essentially built to shield a small number of elites from the coming years of climate change, some critics have coined the term "climate apartheid" to describe it.

“Eko Atlantic City will not even be for the ordinary rich, but for the 'super rich'. It is going be a gated community that poor people can only visit as workers or cleaning ladies. From a social perspective, that is climate apartheid,” says Nnimmo Bassey.

CLIMATE APARTHEID

3

• With an estimated 21 million people, Lagos is the largest urban agglomeration in Sub-Saharan Africa and one of the fastest-growing cities in the world.

• The low-lying and coastal position of the city renders it vulnerable to sea-level rise, erosion, and heavy rains.

• An estimated 3,000 citizens migrate from the countryside to Lagos every day.

Gabriel Ayorinde

At a time when not only Sub-Saharan Africa’s, but also the rest of the world’s coastal cities are experiencing a massive population explosion, Lagos presents two strikingly contrasting possibilities. Bassey hopes that the world’s leaders will find the solution to the future challenge of building climate-resilient cities, not in the exclusive Eko Atlantic City but in the twisted canal systems of Makoko.

“The Makoko Floating School is the perfect example of how coastal cities can respond to global warming,” Bassey says. “It shows that cities are capable of developing in different directions. They do not have to be in a straitjacket where the only solution is concrete, more concrete, and more cement.”

Lagos

Drowning Megacities

back TO TOP

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Mokoko

Makoko

<

>

10 - 10

Drowning Megacities is a web documentary by

Lasse Wamsler, Sune Gudmundsson and Sven Johannesen

Developed with the support of the Innovation in Development Reporting Grant programme of the European Journalism Centre (EJC), funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Photography: Daniel Hayduk (Dar es Salaam) and Tom Saater (Lagos)

Video editing: Journalistbureauet TANK

Drone images: Chris Morgan

Design: Mohsin Ali

Music: Esben ‘Es’ Thornhal

@ajlabs production

© AL JAZEERA MEDIA NETWORK, 2015.