By Khadija Patel and Azad Essa

photography by Ihsaan Haffejee

No place like home

Xenophobia in South Africa

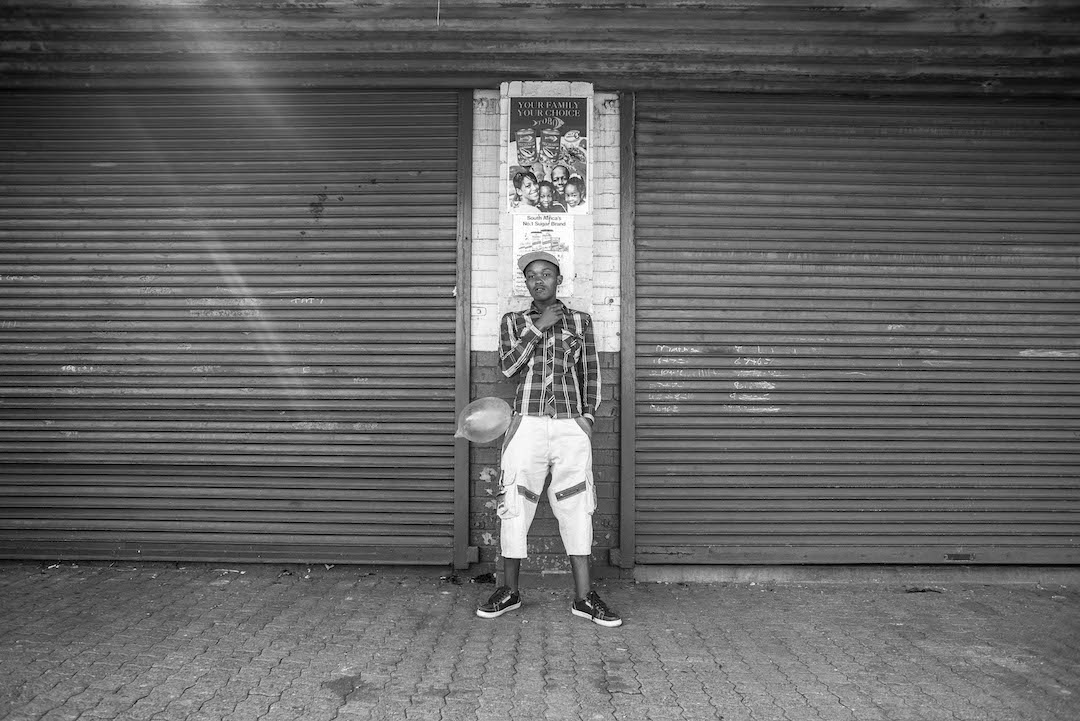

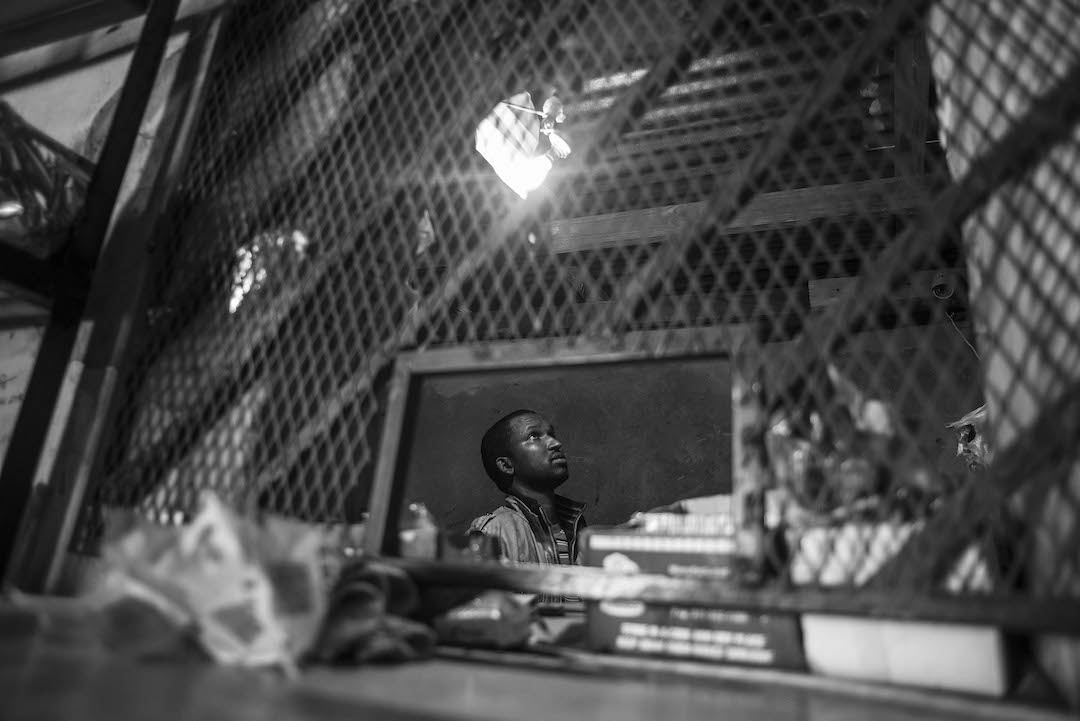

Running small convenience stores in the townships is a dangerous business for foreigners.

Often serving their customers through locked gates, they are accused of spreading disease, stealing jobs and sponging off basic government services like electricity, running water and healthcare.

But as violence against them continues, the South African government insists that criminality is behind it, not xenophobia.

The foreigners

Xenophobia in South Africa | Chapter 1

In a haze of violence in late January,

an angry mob approached a convenience store belonging to Abdikadir Ibrahim Danicha. They pried open its iron gates and looted everything inside. Even the large display refrigerators were carried away.

Danicha's life was upended.

"South African people don’t like us," Danicha, a 29-year-old Somali national, told Al Jazeera, while sitting on his bed in a small room he shared with three others in Mayfair, a suburb popular with foreign nationals in Johannesburg.

The violent outburst that led to the looting

of Danicha’s store began in Snake Park,

in the western reaches of Soweto, when

14-year-old Siphiwe Mahori was allegedly killed by another Somali shop owner, Alodixashi Sheik Yusuf.

Mofolo Central, Soweto

Mahori, a South African, was allegedly a part of a group of people who attempted to rob Yusuf’s store on January 19. His death sparked a week of mob justice, which appeared to be inflamed by xenophobia.

Scores of people were injured and hundreds of stores were looted. As the violence spread to nearby Kagiso, a South African baby was trampled to death.

For the foreign nationals affected by the violence, the actions of the mob were inexplicable.

"I don’t even have clothes … I lost all my things," said Masrat Eliso an Ethiopian national, four days after his shop in Protea Glen, a suburb of Soweto, was looted.

"

I don't have money.

I don't have anything

and I'm scared for my life"

MASRAT ELISO

Calm was eventually restored and most foreign-owned stores reopened. Shelves were restocked and customers returned, poking their arms through the closed metal gates

of the stores to buy a loaf of bread. Groups

of children clamoured to buy lollipops, while tired looking men eyed the fridges for energy drinks.

It appeared to be business as usual, but to the foreign nationals who returned to their stores in Soweto, there was a shared fear

that they may soon be the subject of another attack.

Danicha returned to his shop in Mofolo, another suburb of Soweto, three weeks after the violence subsided.

"I don’t feel safe," he said in early March, outside his partially restocked shop.

He is one of a few hundred thousand Somali refugees in South Africa who have found some measure of success in operating small stores in townships around the country. He is also one among thousands of foreign nationals here who report multiple incidents of persecution.

"

I came to South Africa in 2012 and

I thought life would be easy."

ABDIKADIR IBRAHIM DANICHA

But Danicha's life in South Africa has been filled with hardship. And the scars, which run across the entire left side of his body, act as

a stark reminder.

In June 2014, he and a friend were running

a small store in the Johannesburg suburb of Denver, selling groceries and basic cosmetics when their store was set upon by an angry mob.

"The first day, a group of people came to the shop. They wanted to loot us. We closed the doors but then they started stoning us," he said. "Then, on the second day, they just came and threw a petrol bomb at the shop.

I was inside the shop."

Danicha was one of four people who sustained severe burns in Denver on that day.

Somalia

Abdikadir Ibrahim Danicha

"Everywhere, everywhere I am burned,"

he said. "I was in hospital for three months."

After being treated at the Charlotte Maxeke public hospital, Danicha was then forced to rely on the Somali community in Johannesburg for assistance.

“A brother of mine helped me out by giving me a share in a shop in Soweto.”

Two months later, another mob attacked

his store.

"Unless I have the capital to start another shop, I don’t know what I can do."

Estimates suggest that more than 50,000 Somalis have fled to South Africa since their home country erupted into civil war in 1991.

Many of them have settled in townships across the country, operating small businesses among the poorest South Africans.

While the store in Mofolo has reopened, and Danicha helps his co-owners periodically, he has not been able to contribute to the capital needed to get the store sufficiently restocked.

It is very difficult

to start again

and again"

"

ABDIKADIR

IBRAHIM DANICHA

From Soweto and Kagiso the violence in January spread to Sebokeng in the Vaal delta, Eden Park in Ekurhuleni and Alexandra, in northern Johannesburg.

As researchers begin to unpack the stories

of yet another bout of violence against foreign nationals in urban South Africa,

many of the victims are beginning to feel

that the pain caused was not just the loss

of goods, earnings and trading days.

“We came to South Africa because we needed to save our lives,” Mohamed Rashad, an Ethiopian national from the Oromo community says. He runs a store in Snake Park and is angered by the lack of justice in cases involving foreign nationals.

“The law is forgetting us so soon we will also forget the law,” he warned.

Back at the store in Mofolo, Danicha watches as his co-owners serve customers through

a gate. He is not sure what the future holds for him.

“At first I had a plan but the plan has been destroyed two times now,” he said.

With Somalia still reeling from conflict, he has nowhere else to go.

Despite the ongoing violence, South Africa

is home.

Voices

Somalia

Muhammed Hukun Galle Hassan

I came from Somalia in 2009. And the South African government is good, they let us work for ourselves. I say the government thank you very much and I was working myself and I was looking my food and to trade.

READ THE REST OF MUHAMMED'S STORY

This is how I started, I worked and got together some money, and

I put this money together with other people. Then I acted like a supervisor.

I would go to a place and see the owner of the property where I think

we can make a shop and I say can you give us the lease I’m going to

work in the building here. Then when we make money I don’t take it

all, we are sharing. So if it is, 18, 19, 20 thousand rands ($2,000)

profits, it is shared between five people. That is how we work. When

we make this money here we working hard.

In Somalia there is no peace there. When I ran away from there, I was

not the only guy. And I run because from Somalia there was no

government and I came here where I can stay and make a life in peace.

I got the family there but I don’t have the choice to go back. That

time if I stayed in my country there was no law and order, I was

scared. That one time they shoot me inside the leg, they come here

they help us that time my father passed away. This is the problem in

Somalia.

I want to ask government to look after our safety. We are businessmen.

We are not attacking anybody by coming here. I really really like the

government in South Africa because they allow us to stay here but we

need safety. They must do something about these people who are attacking our business and take everything. I think other people are

jealous.

My shop was closed for 10 days after the attack.

After my shop was looted, we came back, and we fixed it. We bought a

new fridge, we made a new gate and we put new shelves. So now people

think we have a lot of money here, we don’t have the money because

they took everything. Because we also have to buy food, we have

families to feed. But even when I came back, I was told I could not

open my shop.

I went to the police station and complained and told them that some

people have given me this paper that says I must close my shop or they

will kill me.

They give this letter to all the shops. They told us not to open, to

go back to where we come from. They asked me why I am coming here. I

said I live here. They said close your business, go back to where you

come from. They are fighting us.

We called in the police. The police did not care. They did not listen,

they did nothing. They said, “Voetsek!”

We are not feeling safe right now. It’s the police who are supposed

to look after our safety but they say they don’t care.

They listen to other people only. If someone attacks us they don’t care.

But we are feeling scared still. We don’t know what we can do, where

we can go, but we stay. We will see if we die or what.

It’s happening because: We don’t know, they say we don’t want any

foreigners coming here.

I did not have the problem before and I have the the shop for 5 years.

The people here around my shop know me. They know who I am. We are

friends, they know us, we are staying here for a long time. they all

know the area and you can speak we are business people. We are the

good people because we are living nicely. You can see, there is the

good people and the bad people, they are taking our customer away, how you see this people.

There have been crooks who come and steal. We saw like that before.

But not like this, where they come and break the shops and taking

everything that wasn’t sold.

Despite promises of help, the situation on the ground is disastrous and rebuilding almost non-existent.

With help hardly getting through, and so many in need, building materials are scarce and flats for rent even scarcer - and expensive too.

Somalia

Ismail Adam Hassen

Some people come to South Africa by plane. Others come with taxis and busses.

But I took a very long route to South Africa.

I came to South Africa in 2010 and it took me three months to get here.

READ THE REST OF ISMAIL'S STORY

From Juba province in Somalia, I went to Mombasa in Kenya. I spent some time in Mombasa. But things in Mombasa are not good for Somali people.

And one day the police came and they were arresting all the Somalis but they left me because I was very, very thin then. So I heard them say,

“Leave him, he’s too small.” And then from Kenya I went to Tanzania.

Then I went Malawi. From there I went to Mozambique. And from

Mozambique, I went to Zimbabwe and then I came to South Africa.

My family is all dead. I am the only one left.

My shop is open again. With the little goods I saved from the looting

I started again but the shop is still not 100%. We are trying. I am

trying to get credit from the Somali-owned cash n carry to buy more

goods. I don’t feel safe, but what can we do? It’s life.

On the day that my shop was looted, I was sleeping. Snake Park, where

all the trouble started, is not far from my shop. So these boys, many

boys, came to our shop. I was sleeping. And my “brother” saw these boys coming to the shop. He woke me. These guys took our money, our clothes, everything.

We ran away through the back entrance. They took everything. And then the police came past there. And the police looked at these boys taking the things from our shop and they did nothing. I saw the police giving bread to a mama.

I asked the police why they are giving our stock like this. And they

told me to keep quiet or they will give more. Other police I saw

coming into the shop and they took airtime, Grandpas (headache

tablets) and other things. If I had a camera at that time I could take

the photos of the police. It was almost five cars of the police.

The police were asking us for our guns, saying, “Where is your gun?”

But we don’t have a gun.

I remember, when when we were leaving, the police told us, to give

them a “cold drink” if we want them to help us. When I told the police that we don’t have money, we are suffering, the police said,

“You are living here in our place and you are foreigners.”

So we gave the police R200 ($20). So then the police helped us, and I

saved a little goods but most of it was already damaged. I did not

even have clothes. I came to Mayfair with just my little stock.

South African people don’t like us. The government allow us to stay

but the people don’t like us.

They call us names. And I believe this looting and things will happen

again at any time. We don’t have power to stop this. Only the

government has power. We don’t do anything criminal. We are serving

the community. We keep our shops open till late so that people who

come home late after work can come to our shop and buy things. It’s

only government that can stop this trouble.

Somalia

Salat Abdullahi

We can be attacked anytime here in the shop.

It is like an ambush attack. We are not safe here.

We can’t even say that we will sleep peacefully tonight because we don’t know what we will face tomorrow.

READ THE REST OF SALAT'S STORY

The South African government is not bad. But the people… they really don’t like us. Even when they come to the shop, we are giving them big discounts because we sell everything very cheap. But they are abusing us.

Even the police when they come to help you they first take money

from you.

There is nobody that helped us to get so far in South Africa.

We did by ourselves. I am here for almost two years but I can’t leave

South Africa.

We have problems in South Africa but it is still better than Somalia.

I am from Kismayo. If my country has peace I want to go back to my

country. It is my country. I love my country.

Family? (His face creases with deep emotion) I don’t think I have any family any more.

They have all passed away. You see, the problem in Somalia is if you

want to be safe you have to join Al Shabaab, or else they will kill

you. And I can’t join Al Shabaab. They kill innocent people. I’ve seen

this.

There is no law.

What we need is more security from government. We just want to be safe.

Bangladesh

Nasser Abu

I am in South Africa as an asylum seeker.

You see, in my country, Bangladesh, there are political problems. We are suffering. So we’ve come here honestly. We’re not robbing anybody. We are not doing any crime. We just come here

to do business. And we hope to help South African people also.

READ THE REST OF NASSER'S STORY

As a Bangladeshi in Soweto, I don’t know of any Bangladeshi who has made problems in Soweto. We have never fought with anybody and we have never shot anybody. From our side, nobody can complain about us.

This shop wasn’t affected by looting. The shop across the road was

looted but we managed to close our shop before the looters got here.

Right now it’s okay but I have three, four other shops in other places

in Soweto that were looted. So now I’ve joined a group called Township

Business Development South Africa (TBDSA), who have been speaking to

government in Pretoria so now we are hoping to fix the problems with

the local people here.

We do not want to complain about anybody. We just want to open our

shops and do business. I’ve never been affected by violence in my

businesses like this before. I’ve been robbed a few times. Just the other day my uncle was robbed of R20,000 ($2,000) on his way out of Soweto.

We stay here, we have to have a good relationship with the people who come to our shops.

But we need more protection from the police. I’ve been in South Africa

for seven years.

If, in future, government says we have to pay taxes, I will pay tax

but government must give us safety. My business has been registered

already.

I’ve never had a bad experience with the South African police. The

Diepkloof police have been honest with us, they don’t take money and

things from us.

I don’t hire South Africans in my business because they steal, or

others work for a day and ask for goods from the shop, saying they

don’t have food at home and then I don’t see them again.

When we have hired South African people they do wrong things with us. If government says I have to hire South Africans then I will, but I don’t think it will work. But I won’t complain. I think I could hire two South Africans.

I will never shoot a tsotsi (thief) stealing from my shop. Look, say a

tsotsi steals a can of Red Bull from my shop. That Red Bull costs R18.

I must shoot him for R18? No, nobody’s life is worth that.

Analysis

Ebrahim Khalil-Hassen,

Public Policy Analyst in Johannesburg

Al Jazeera:

Is it hard to do business in South Africa?

READ HASSEN'S RESPONSE

I wouldn’t say there are many obstacles starting up an informal

business, particularly if you’re just going be trading. You are buying

stuff and then selling it; there are no real obstacles. You just wonder why more people don’t do it.

The ease of starting up a business in a township depends largely on

how legal you want your business to be. There actually is not much

that needs to get sorted out. My understanding is that, procedures

like securing premises, particularly in townships, are not at all difficult. I think the key thing there is that the businesses are not all in busy areas, they’re all over. Some businesses are even run from people’s homes.

The success of foreign owned stores in the townships is owed to the business models that a lot of the foreigners bring through to their

businesses. Collective buying is one trick. But if you look at the innovation that has been used in a lot of these foreign owned

businesses, it’s the small things but make a huge difference in terms

of running a successful business. So you don’t sell half a kilo of salt, you sell one hundred grams of salt, in poorer communities that’s

particularly the case - single serving.

The other issue is around

credit, most foreign owned businesses do provide credit and they don’t

charge interest, so that assists low earning households.

The

history

Xenophobia in South Africa | Chapter 2

In May 2008, 62 people were killed in a wave of xenophobic attacks across townships.

Foreign nationals, mostly migrants from Somalia and Ethiopia, were dragged through the streets of Alexandra, barely a few kilometers from Johannesburg’s plush Sandton suburb, and “necklaced” -

a throwback to the summary execution tactic used in the Apartheid days.

A rubber tyre, filled with petrol, is forced around a victim's chest and arms, and set alight.

In an instant, the story of South Africa’s much-touted rainbow nation of black, white and brown people happily living together, fizzled away in an outburst of vengeance.

Tens of thousands of people were displaced, forced to seek refuge in churches, mosques and even police stations. In the end, it took military intervention to quell the violence.

South Africa is a nation of multiple ethnicities, languages and nationalities.

From the Zulu and Xhosa, to the Dutch and the British. Somali and Tutsi to Indian Tamil and Gujarati, Chinese and Zimbabwean.

However divided, unequal, and structurally flawed, South Africa is home to a very diverse population of people. A country with deep pockets, it remains attractive as a home for migrants, some of them seeking greener economic pastures, others safety and security.

The economy relies heavily on migrants, be it to make up for a massive skills shortage or as cheap labour in farms and mines.

Despite the violence meted out to foreign nationals, tens of thousands continue to seek asylum there, as many as 60,000 to 80,000 per year.

According to the UNHCR, there were almost 310,000 refugees and asylum seekers in the country as of July 2014. By the end of 2015, this number is expected to top 330,000.

Xenophobia in South Africa is not new.

Some, like Michael Neocosmos, Director of Global Movements Research at the University of South Africa (UNISA), recall anti-migrant sentiment in the early nineties, when the new government was in the midst of planning new economic policies and politicians of all stripes began drumming up anti-immigrant sentiment.

“It is important to recognise that xenophobia can exist without violence. And it’s not sufficient to simply recognise it when people start killing each other,” he said.

A survey in 1997 showed that just six percent of South Africans were tolerant to immigration. In another survey cited by Danso and McDonald in 2001, 75 percent of South Africans held negative perceptions about black African foreigners.

In a most painful of ironies, many South Africans associate foreign black Africans with disease, genocide and dictatorships.

The ills of Apartheid: skin colour, complexion and passes, in this case citizenship, are still the determinants of a better life, or discrimination.

Little illuminates this disparity more than the infamous Lindela Repatriation Centre, built in 1996 for undocumented foreign nationals entering the country. Lindela, outside Johannesburg, has been a scene of abuse, corruption and incessant overcrowding. But the undocumented are also held at police stations, even army bases.

“There is evidence that even in 1994, the records have shown that foreigners were thrown out moving trains because they are killed of bringing diseases, taking jobs, the same rhetoric we hear today,” Jean Pierre Misago, a researcher at the African Centre for Migration and Society at the University of Witwatersrand, said.

“It didn’t start or end in 2008. It had been building up,” he said.

And build up it did. In 1998, three

foreign-nationals were killed on a train, between Johannesburg and Pretoria. In 2000, a Sudanese refugee was thrown from a train on a similar route. The reasons were all the same: blaming foreigners for a lack of jobs,

or economic opportunity. In 2007, a shop in the eastern Cape was set alight by a mob.

The violence that escalated in 2008, was distinctive and decisive. It affected black, African foreign nationals; poor and disenfranchised South Africans; in the townships, but there is no evidence to suggest white Europeans were attacked,

or those from the Indian subcontinent.

A very particular demographic paid the

price, but researchers remind us that at least one third of the victims were actually

South African. Xenophobia is not a problem unique to South Africa.

With so many economies battling recession for the better part of the past decade, the deadly triad of competition-survival-blame has seen fear of the foreigner rise across the globe.

“Xenophobia is experienced in the north and the south, in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) regions and other countries. It’s a worldwide phenomenon,” Misago said.

But, contrary to popular belief, xenophobia in South Africa is not just a problem of the poor.

A national survey of the attitudes of the South African population towards foreign nationals in the country by the South African Migration Project in 2006 found xenophobia to be widespread: South Africans do not want it to be easier for foreign nationals to trade informally with South Africa (59 percent opposed), to start small businesses in South Africa (61 percent opposed) or to obtain South African citizenship (68 percent opposed).

The violence of 2008 was still shocking.

The country fell into mourning; South Africans understood that the innocence of democratic transition, purposefully packaged in cotton and celebrated with confetti, had finally

been taken. The mask had fallen.

This was a country now reverberating under the internal schisms of rising dissent and desperation. The South African government, for its part, refused to label the violence as ‘xenophobic’.

Then President Thabo Mbeki, at the very end of his second term in office, said those who wanted to use the term were “trying to explain naked criminality by cloaking it in the garb of xenophobia”.

When I heard some accuse my people of xenophobia, of hatred of foreigners, I wondered what the accusers knew about my people, which

I did not know ... and in spite of this reality, I will not hesitate to assert

that my people are not diseased by the terrible affliction of xenophobia which has, in the past,

led to the commission

of the heinous crime

of genocide."

"

FMR. PRESIDENT THABO MBEKI

The government attempted to reduce the perception of the terror meted out on foreign nationals as benign, unexceptional acts of criminality. If they were orchestrated attacks, they said, ‘a third force’ was behind the violence, apartheid parlance for acts perpetrated by outside forces, or intelligence agencies.

“Of course violence against foreign nationals is criminal. But it can be criminal and xenophobic, it doesn’t have to be either or,” Misago said.

And even before the onset of the latest wave of violence in 2015, there was more to come.

In early 2013, a young Mozambican man named Mido Macia was tied to a police van and dragged through a street close to Johannesburg by officers. He had parked his taxi on the wrong side of the road.

The violence was captured on video

and spread across social media. Resounding condemnation from the middle classes in South Africa and the international community followed. President Zuma himself condemned the incident, but there was still no acknowledgement that these incidents constituted ‘hate crimes’.

When the riots broke out in Soweto in January 2015, it surprised no one.

Analysis

Jean Pierre Misago

Researcher at the African Centre for

Migration and Society at the University of Witwatersrand

Al Jazeera:

Does South Africa have a history of violence against foreign nationals?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

What’s happening now is not new. It’s happened long before 2008, but

it peaked in 2008 when so many people died and many people were

displaced. It never stopped since then.

So that we are seeing violence

again in different areas of the country is no surprise to us. The way

we see it is that government has always tried to call it criminality,

insisting that there is no xenophobia behind it but from a research

point of view that’s not correct.

Because, of course violence against

foreign nationals is criminal. But it can be criminal and xenophobic,

it doesn’t have to be either or.

Al Jazeera:

How is it xenophobic?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

What’s happening now is not new. It’s happened long before 2008, but

it peaked in 2008 when so many people died and many people were

displaced. It never stopped since then.

So that we are seeing violence

again in different areas of the country is no surprise to us. The way

we see it is that government has always tried to call it criminality,

insisting that there is no xenophobia behind it but from a research

point of view that’s not correct.

Because, of course violence against

foreign nationals is criminal. But it can be criminal and xenophobic,

it doesn’t have to be either or.

Al Jazeera:

Do we know how it was created culturally? And what’s currently feeding it?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

There are different accounts and scholarly accounts on what’s causing xenophobia. And one thing I can say is that xenophobia is not unique to South Africa. It is experienced everywhere, in rich and poor countries, in the north and the south, in the SADC regions and other

countries. It’s a worldwide phenomenon. Migrants, especially poor migrants are affected by these kinds of feelings and sentiments.

One account is that xeno or the tendency to fear the stranger is

inherent in human nature. Some scholars give the example that when

you go to visit family and you touch a kid and the kid doesn’t know

you the reaction is what? To cry, as in “to put away, and I want to go

back to my mum”. By this theory, the feeling is natural. But the other theory says that it is actually a social construction. So, this suggest that yes, even if there might be initial fear of the norm, after a while the kid is going to warm up to you once realizing you are not a danger.

It becomes a problem when there is something that perpetuates that

fear, the feeling that this person is bad. And that’s where the social

construction comes in. And from that perspective in South Africa, we

see the legacy of the past, for instance where the movement of people was perceived as a threat to residents and their livelihoods.

People were told to stay where they are: this is where you live, this

is where you get your livelihood. Don’t move. The current dispensation has not been able to shake off that legacy. Movement is seen as a problem, as a threat to peoples’ lives, and we have to remember it’s not just about foreigners.

And so in South Africa the main explanations are the legacy of

segregation; this legacy has not been addressed. And even the current leadership keeps using that kind of rhetoric: but calling immigrants or outsiders as criminals as bringing diseases, and blaming them for all sorts of socio-economic ills we face. From the national level to local level where local leaders blame the presence of foreigners for

the shortcomings of service delivery. "We can’t deliver because so

many people keep flocking here". "Hospitals can’t cope because we are too many Zimbabweans coming in". "Not enough housing because too many foreigners". "Not enough jobs because foreigners are stealing them".

That kind of rhetoric forces that feeling that foreigners are here to

take what is ours, what we deserve, and what supposed to be ours. And

we don't have what we want, "because of the presence of outsiders".

Michael Neocosmos

Professor and Director UHURU

Unit for the Humanities at Rhodes University

Al Jazeera:

How different is South African xenophobia different to what we see in

Europe, for example?

READ NEOCOSMOS' RESPONSE

It’s not all that different in what was happening in other countries

in Europe where those in power have been creating precisely an

exclusionary understanding of who the nation is. People who migrate

from elsewhere are outsiders who come here to steal…including

apparently stealing our democracy. It’s within that context that we

have to understand this rise of xenophobic violence and attitudes more generally. The violence couldn’t take place if the attitudes are not

there, and we have to insist on

the fact that xenophobia is not

a problem of the poor.`

Al Jazeera:

Who in SA is xenophobic?

READ NEOCOSMOS' RESPONSE

You can see from various survey, attitude surveys taken through the

years, that in fact xenophobia is widespread throughout all racial

and ethnic groups, all gender groups, all political party groups- supporters throughout the country. In other words, xenophobic attitudes are prevalent irrespective of who you

are talking to.

And there is also a culture.

When various individual politicians

speak, they don’t just simply speak and then everyone forgets about

it. It creates a culture. It creates

a culture in the same way as the

people in the media create a culture by repeating discourses over and

over again . And in the media, there was a systematic targeting of

immigrants, has calmed down, except for one or two well known cases. But in the 1990’s even supposedly serious newspapers were going on and on about Nigerians all being drug dealers. This creates a culture.

The

mob

Xenophobia in South Africa | Chapter 3

On a busy Monday morning in mid-March in Soweto, Mphuti Mphuti, the acting head of the South African Spaza and Tuckshop Association, appeared on national TV, waving his South African identity document.

“Your government is saying this document means nothing. They are saying foreigners are equal to you,” Mphuti said.

In the weeks following a wave of attacks against foreign-owned businesses in Soweto earlier this year, groups similar to this association and claiming to represent some 3,000 businesses, have been particularly vocal about the presence of foreign nationals in the townships.

“There is tension, there is anger, especially amongst those who fear competition from the so-called foreigners,” said William Veli Sithole a 56-year-old food vendor in Dobsonville.

However, business owners in the country are not likely to be found hurling petrol bombs, or rocks, at foreign owned shops. Often it is a mob, made up of the township mainstay of unemployed youth that form the front lines of service delivery protests, vigilante justice, and repeated attacks against foreign nationals.

“At the time of looting the mob rule takes over, you do not have time to reason; you (only) have time to do what others are doing,” Sipho Mamize, a representative of the NGO Afrika Tikkun's Wings of Life Centre, in Diepsloot, told the national broadcaster.

But while the gall of the mob shocks other South Africans, their activities have also managed to escape censure.

Mphuti, however, said that at the heart of these township battles is the dereliction of government’s duty to its people that has spurred the resentment of foreign nationals here, culminating in the violent looting of foreign owned stores in January.

The people expect a lot from the government, he said.

For others, like Cynthia Khanyile, a street vendor in Jabulani, the blame lies elsewhere.

“I hate foreigners. I really don’t like them. They take business away from us. We work hard, but then the foreigners come and take our business and our jobs,” she said.

According to 2015 figures released by Statistics South Africa, 21.7 percent of all South Africans live in extreme poverty. At least 53.8 percent survive on less than $75

a month.

It is the politics of survival.

The close knit structures of migrant communities which foster micro-lending and bulk buying schemes popular among Somalis, for example, has only served to disempowerment among locals. The upward mobility of those “from the outside” amidst local inertia is frustrating.

“As South Africans, we still cannot speak about the fruits of this democracy,” Mphuti said.

Sociologist Devan Pillay said that despite the redistributive rhetoric of the ruling-party, the new South Africa has “unleashed a socio-economic system of market violence against the majority of the population.”

Here, the perpetrators of xenophobic acts are victims of the violence meted out by the market.

“Whereas in other instances this might have taken a gendered form, or an ethnic form, in this instance, the convenient scapegoats were easily recognisable foreign nationals,” Pilay writes in “Go Home or Die Here”.

South African townships are a scene of daily pandemonium with residents protesting against poor service delivery, low levels of development or improvement to their lives. Twenty years on, the majority of South Africans continue to live on the margins.

It is this desperate level of inequality, social scientists have warned, that continues to drive resentment and instability.

The attacks on foreigners do not happen in

a vacuum, nor can they be explained simply by hatred of all things foreign. This, after all, is a country still searching for social and economic reconciliation.

We have seen very little government intervention and upliftment of small businesses in the township,"

"

MPHUTI MPHUTI

“And that’s why we are saying before government can say we are equal with foreign nationals, government must empower small South African businesses. But the critical thing is, South Africans must in the interest

of people who carry the ID book, the green ID book is our license to get preferential treatment from government.”

Days later, a formal agreement between foreign traders and South African business leaders was eventually reached.

The drama of Mphuti’s TV soliloquy was perhaps necessary to assert the will of

a subdued population. He understands the discontents in Soweto, and he also knows how those discontents spill out onto the streets.

Voices

Dobsonville

Kwanele Godfrey Gumede

The trouble started in Snake Park and the violence spread everywhere. We were here in the city, and each and every shop is owned by the Somalians. You see what started this, we don't want these people here.

READ THE REST OF KWANELE'S STORY

Because when we see lots of shops owned by this people and when we see the shops that was owned by our peoples have been closed.

Each and every shops that was owned by our people has closed. Our brothers our sisters had shops, but when these people come, nobody was buying from our shops, for example: you can sell less price, our people will seek products that's high cost prices, so we feel it's not fair.

I looted their shops, I took the stuff from the shop. We were many, many people, young people, older people, men and women, everybody was

angry. There was no leader, it was just us fighting them. We broke

their shops and took everything. We were all over Soweto. We went this

side, and then go another side, finish that side and go another side.

We were busy looting all over the place.

I didn’t get caught by the police but some of my friends were locked

up. Then the police released them after two, or three days.

But now the Somalians are all back and we feel angry, angry, angry, we

feel the law is failing the citizen. Because all of them they do

business, and we know for sure they don't pay taxes, because they pay

taxes to the police. The police they come here and they demand

cold-drinks, biscuits, snacks, sweets, and cigarettes from them. The

police are involved in everything, because the police they come here

and they demand.

I was working before but this year I don't have a job.

In this township there are a lot of young guys who have a matric

certificate but no jobs. I don't have a matric, but when I see my

friends, there are many people living here who are not employed. So

I’m staying here, each and every day I can see things are not the

same. All of my life I was staying here in Soweto. There are a lot a

lot of people without work, I can't say that they don't want to work,

but many of them they are trying, but, there is no change. I can't see

change.

I can say even if one shop, they hire maybe two, or three people, it

will make a big change in our country, I can't say in our country in

our city. Because in our city there is full of them.

Yes, when I can see our people they don't have enough strength to open

their shops again because everyone buys from the Somalians shops. Yes,

I also still buy bread, milk and airtime from the Somalians’ shops.

I can buy the bread from South Africans shops for R12, for example,

but the bread by the Somalian people is R11. Everyone will go to

Somalian people, because of what, one rand. That's it.

Orlando East

Jameel Buhle Gobile

I was born in Soweto, I know what is going on here. There is a way of dealing with this problem. I don’t want to blame government but people are hungry. Me too, I’m hungry. And people will do anything when they are hungry.

READ THE REST OF JAMEEL'S STORY

People have listening to many false promises from people to employ

them, or to create employment. And then on the other side the foreigners are trading and they are successful here among people who are hungry.

And then when there are problems it is usually sparked by service

delivery because when protests against service delivery happens,

people begin to take advantage of foreign owned shops and then they

drink. If you look into it, after the looting has taken place, two

days later, that service delivery protest also dies down because

there’s nothing left to loot, nothing to burn, no property to damage, or ransack. What we saw happening in January, we saw young and old,

carrying things from foreign shops like they have just gone shopping.

You see, people are hungry and they are unemployed.

For me the solution lies in foreign nationals, who are large in number, to hire a South African in each shop they run. So now, if we estimate, there are 5,000 foreign owned shops on the East Rand, then 5,000 South Africans can be employed there.

People wait for an excuse to raise their issues, like we see what

happened here in Soweto after the child was killed in Snake Park. One

child was killed by one foreigner but all foreigners were affected. So

you see, people wait for an excuse to express their frustration against foreigners.

But you see, if we say the foreigners must go, but if we do that, I think we are bringing economic sanctions to our our country. We depend on foreigners and on imported goods also.

Dobsonville

William Veli Sithole

In January, it started when they said a schoolchild was killed by foreigners. Anger boiled, and then it sort of took over even some

criminal elements who saw a way of destabilizing the shop owners.

READ THE REST OF WILLIAM'S STORY

My community was drastically affected because in the aftermath of the attacks and looting, people suffered. They were forced to go to

faraway places like Shoprite and other shops to go buy food.

We have gotten used to foreigners, they supply most of the things that

we use in our houses and they are not far from us. But now there is a

criminal element you must know of. The drug addicts, they are the ones

who are being used by certain local shop owners who fear competition

from the foreigners.

I don’t fear competition. The foreign shopkeepers are like my brothers. Why should I fear them? They are as human as I am.

I tell you what though, the government and the governments of those foreign nationals struck a deal of which we know nothing of, to have these people, to be brought in, because one morning we woke up they were here, hiring buildings, making shops in people’s houses, even though the rents are exorbitant but they are paying. It’s their own

deal the shop owner and the owner of the house.

Foreigners are also trying to make a living for themselves, even

though somewhere, somehow they don’t pay tax, while it’s a government

issue to handle, its not for me to question how the government goes

about their own stuff regarding taxes.

Our government also knows, the State Security people, know who the

perpetrators of the violence are, and they looking the other way

sometimes. And mostly, it’s because of power hungry people that cause all those conflicts that only if they could, they should sit around the table and resolve their differences for the sake of peace.

But our government, must address poverty. It is poverty that makes

people lose their minds.

We are a peace loving nation. And we accommodate people from outside.

We need to work together to keep things running smoothly for the sake

of peace because no parent would like to see their child perish in a

war.

Analysis

Jean Pierre Misago

Researcher at the African Centre for

Migration and Society at the University of Witwatersrand

Al Jazeera:

Who is responsible for the violence? Individuals or groups?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

It’s a group of people coming together and deciding to attack. Most of the time violence happens after a general public meeting, organised by the community leaders, where foreigners are discussed, and then a decision is taken to remove them from the community. In those

meetings, it a matter of taking charge: "this is the situation, we

can’t continue like this", or "there is nobody else to take care of this issue," or "It’s now us who has to deal with it".

So there is clear evidence that violence happens after local leaders,

and they don't have to be local government leaders, meet and decide. And this is another issue: often local resident groups are more

powerful than the local government.

Local council members are often reminded there are other powerful

groups calling the shots, and those are the ones they listen to, and

in some instances, these informal leaders or groups have specific

incentives in the removal of foreign nationals because it consolidates

their power and their power comes with economic benefits.

We tend to think that community leadership is a voluntary kind of

business, but it’s not. It’s paid, it’s a form of income generation,

because community leaders charge you for a service. If you have a

problem, they don’t hear the problem before you give them something.

They locate space for big sharks; they locate land, they resolve

conflicts and for that everybody pays. So the more legitimacy, the

more clients, and the more economic avenues they have. So that’s why we often conclude that the violence we see is politics of other means because it has political and economic motives behind it.

Even if the general communities say we have no problem with foreign

nationals because actually we benefit from their presence, their voice gets drowned out. And the police and everybody doesn’t do anything about it. And the problem is, those are not the amongst those

arrested. Only those caught in looting and taking things from the

shops. But the true perpetrators who are behind the violence are not

touched and they continue to influence the next…whenever they feel it

suits their interest. That’s why we have seen some areas have become

scenes of repeated violence because the perpetrators are still there, the investigators are still there…there didn’t do anything about the focus…

Al Jazeera:

Who are behind the looters?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

We haven’t seen any investigation beyond the looters to look at who is

behind the violence; who organised and who reaps the benefits. So

people get caught looting, they are released after a few days but the

instigators are still on the streets. The same will happen in Soweto.

So generally speaking, there hasn’t been any systematic sustained will

from government, the political leadership and the police to fix this.

And it sends out a very bad message. And when there is no political will, there is noone you can call for protection. So what do you do? You try many many things, and that’s where we are now.

Al Jazeera:

Does the larger community never ever

intervene?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

In some instances, very few, but in very interesting cases, community

members have resisted saying that we cannot attack foreigners because we been living with them for a long time. They actually protected them. Even Landlords organising to protect the people who are renting.

But in some of these cases, foreigners have also been forced to agree to certain conditions. Like not selling goods cheaper than the locals, or not opening a certain number of shops.

The

officials

Xenophobia in South Africa | Chapter 4

Mxolisi Eric Xayiya, an aide to Gauteng Premier David Makhura, took photos of the fridges and assortment of goods covered in thick plastic at a Somali-owned wholesaler in Mayfair.

He was being ushered through the area west of the Johannesburg city skyline days after foreign traders were attacked in Soweto some 20 minutes away. Foreign owned stores were looted, foreigners were attacked and their lives threatened.

There, the parking lot of Awash Cash & Carry appeared to be overrun with the salvaged remains of foreign-owned stores.

“We only saw the foreigners leaving but we didn’t know where they were going,” Xayiya said in late January.

At the time, police were still battling to contain the violence and more than 100 alleged looters had been arrested. The violence threatened to spread even further.

And in an impassioned address to more than 500 affected migrants that day, Makhura condemned the violence, but insisted that it should not be seen as anything other than an act of criminality.

“What we have seen happening, ladies and gentlemen, is not xenophobia, it’s criminality,” Makhura told the crowd. “We have gone out to the community to talk, telling our community members that nobody in our communities must try to defend criminality.”

As Makhura continued to condemn the violence, he also commended the police for moving migrants out of what he called “difficult areas”.

A day after Makhura addressed migrant traders, flanked by senior police officials, the City Press made a shocking allegation.

The Johannesburg-based Sunday broadsheet said that people arrested in connection with looting foreign owned stores in Soweto that week claimed local police had spurred them on.

“Cops told us to loot,” the headline said.

Ten Soweto residents in various parts of the township, who had admitted to looting, told the paper that the police had either join in the looting, or looked on while they helped themselves to goods and fridges from foreign-owned stores, while victims raised allegations of police complicity, corruption and neglect.

Two days later, speaking on SAFM, a talk radio station owned by the public broadcaster, Lieutenant General Solomon Makgale, spokesperson for the South African Police Services vehemently rejected City Press’ claims. He said all allegations had to be registered as complaints to be investigated.

However, Makgale admitted that one particular police officer who had been caught looting toilet paper in a widely disseminated video had been identified and action had been taken against him.

“Unlike previous administrations, we don’t brush things under the carpet,” he said. “Any complaints of misconduct by police officers will be investigated without prejudice.”

The South African Human Rights Commission said its research has shown that “negative perceptions of and attitudes to justice and the rule of law abound at the level of affected communities”.

This then points to a “poor relationship between communities and the police and wider judicial system”.

Attacks against foreigners have continued. Researchers say recent bouts of violence against foreign nationals have already outstripped the carnage of 2008. Still no official mention of ‘hate’, or ‘xenophobia’; the language carefully coiled.

In fact, language goes to the heart of the problem, with South Africa conflating rights with nation-state citizenship, despite the promises of the Constitution, to protect all. When the South African government speaks of justice, rights or solutions, the emphasis on citizenship is marked. In so doing, Zuma’s administration, time and time again descend to the very games engendered to create outrage on the street.

In February, following January’s attacks, President Zuma spoke of a “need to support local entrepreneurs and eliminate possibilities for criminal elements to exploit local frustrations.”

And even as Minister of Small Business Development Lindiwe Zulu, recently established a Task Team to look at the underlying causes of the violence against foreign-owned businesses, her point of departure left observers beleaguered. Zulu was reported to the Human Rights Commission for inferring that foreign-business owners in South Africa’s townships could not expect to co-exist peacefully with local business owners unless they shared their trade secrets.

“Foreigners need to understand that they are here as a courtesy and our priority is to the people of this country first and foremost,” she was quoted as saying.

Minister Zulu later clarified her remarks, but the damage it seems, had already been done.

Analysis

Jean Pierre Misago

Researcher at the African Centre for

Migration and Society at the University of Witwatersrand

Al Jazeera:

Is there a vacuum of governance that contributes to the problem?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

Even before these actions are instigated, organisers weigh up the

costs to the benefits. And if the benefits outweigh the costs it is

because governance in that specific locality allows it. So there is no

accountability, nobody is held accountable, the police do not

intervene, the local councillors are not going to help the police and

this and that.

The socio-economic and legal controls are in favour of the instigators. In literature they say this happens when social controls are weak. But this is not always the case. Sometimes we see strong leadership is actually behind the violence, using the same social controls to actually mobilize communities toward violence.

The point here is that: violence doesn’t happen if the governance of that area does not allow it. And when I say governance I refer to what is what is broadly defined: moral, legal, social, police, everything

combined. So that kind of governance allows for what is known as a political important structure for violence to take place.

Al Jazeera:

Where do we see violence?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

We see violence in areas where… the

“official” leadership- from government is either directly involved, as in they’re the ones telling communities to attack foreigners, or complicit with the organisers.

The leadership does not want the state to stand in its way because they, the fear of losing their political positions. That’s the second.

The third scenario is when the

leadership is completely weak and has been taken over by those other

informal groups who see the use of violence as benefiting them, or

responding to their socio-economic interests.

That’s why we see violence not happening in all localities where we

see the similar conditions- you have poverty, inequality, poor service

delivery in many areas, but we don’t see violence in all areas.

The activists

Xenophobia in South Africa | Chapter 5

Addressing a group of around 300 migrant traders in early March, Amir Sheikh, the chairperson of the Somali Community Board in South Africa, appeared confident. Weeks after violence against foreign nationals erupted in Soweto, he was relating news of progress.

"We have had three meetings with the Minister of Small Business Development and we have given her a briefing of the challenges you face in the township, and what we think is the cause and the solution," Sheikh said.

We know that things are much better now but we don’t want this to happen again."

"

AMIR SHEIKH

Most of the displaced foreigners had been restored to their stores and a fragile calm had been negotiated. Representatives from both the community and the South African business community in Soweto continued to meet with government to negotiate sustainable conditions for foreigners and South Africans to coexist. Sheikh told the assembled migrants that a cohort of lawyers had offered to take up the case of traders who were affected by the violence in Soweto earlier this year.

The victims of the Soweto violence certainly have a case.

The South African Constitution, along with various international treaties ratified by the South African government, ensures the protection of all persons who reside within the country from violations to the right to liberty and security of person.

And when it comes to cases of violence against foreigners, the state is particularly obliged to protect the victims from individuals who perpetrate the violence.

This time, however, legal redress is not being sought.

Sheik said its the safer, more practical option. He said that two years ago, Ethiopians, Somalis and Bangladeshis were attacked in Duduza in Nigel (east of Johannesburg).

“They actually interdicted the councillors, and the chairperson (of ANC Youth League), and these people were even all detained for up to one week .… But today you go to Duduza and and there is not even a single shop belonging to us there.”

Foreign nationals are reluctant to seek legal redress because of the consequences court cases often inspire. After all, how does justice protect the returning migrant looking to reintegrate into a society already hostile to foreigners?

Lessons learned, leaders of the migrant communities are now determined to prevent a mass exodus of foreign traders from Soweto. With more than 1000 foreign-owned shops in the township, Sheik says: “As long as we can co-exist and agree on certain terms, we don’t want to go the legal route.”

A South African Human Rights Commission report in 2010 (pdf below)

found that “the judicial outcomes for cases arising from the 2008 violence have limited the attainment of justice for victims of the attacks and have allowed for significant levels of impunity for perpetrators”.

About 180 people were arrested in connection with the looting and violence in January. It’s unlikely any of these will result in convictions.

Neocosmos says that the lack of convictions in cases of violence against foreign nationals in South Africa strips the government’s approach through the criminal justice system of any efficacy.

“I know one person was convicted for throwing a guy off a balcony in Durban. How many people are in prison now as a result of those murders? These are murders that were committed on camera in front of everyone. How many people have been convicted?”

The best known case of xenophobic violence in 2008 is of “The Burning Man”, Mozambican national, Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, who was burned alive in the Ramaphosa settlement in full view of the world’s media.

The case was closed in October 2010 with the conclusion that there were no witnesses and no suspects. According to the Sunday Times newspaper, a single sheet of paper indicates detective Sipho Ndybane's investigation:

"Suspects still unknown and no witnesses.” The lack of political will screamed through the short conclusion.

Just over a month after January’s violence against foreigners in Soweto, reports emerge of a petrol bomb thrown at a foreign-owned store in Doornkop. This time, it’s an Ethiopian national that has incurred severe burns. Police say they arrested nine people in connection with the incident.

Two months later this man is still in hospital. No word about his belongings or livelihood. The work of ‘a mob.’

Meanwhile, Abdikadir Ibrahim Danicha,the Somali national who was burned after his shop was petrol bombed in Johannesburg last year, is determined to have his case solved in court.

“I’ve been to court six times already for the one case about public violence and damage to property,” he said. “But the other case, about me burning, I’ve not yet been called to court about it.”

Danicha was one of the traders in the crowd that was addressed by Sheikh and the leaders of the newly-established “Township Business Development-South Africa” group. He is confident that the route chosen by the leadership, the choice of negotiations with government and Soweto business leaders is the right option.

“We have to try to work together,” he said. “Because there is nowhere else we can go.”

Voices

Marc Gbaffou

CHAIRPERSON, AFRICAN DIASPORA FORUM

I moved to South Africa from Cote d’Ivoire, in 1997 and in my experience, South Africa can

be very good, and very bad.

READ THE REST OF MARC'S STORY

When you meet people who are not selfish, who know how to liaise with

other communities, who know how to regard other communities as an

asset, then South Africa becomes interesting.

But South Africa becomes very bad when you have your own brothers and sisters beating you, chasing you away from the community, telling you that you are not part of them. This South Africa is very, very bad.

In 2008, I personally sent 700 people back home because they didn’t

feel safe to remain in South Africa.They called on us for help. And with the aid of a local newspaper, we were able to voluntarily repatriate these people.

We strongly believe that the motives behind the attacks against foreign nationals are purely political. It is important that we point out that each time an election is approaching then migrants are being targeted.

We say this cannot continue. Our community members are not

scapegoats for the problems of South African communities.

South Africa is very good when you meet with nice people, open minded

people who want to change the world, and who want to change the world for everyone, not just for themselves.

I think that we can live together, making use of each other, instead

of isolating yourself and being scared of everyone.

Amir Sheikh

CHAIRPERSON OF SOMALI COMMUNITY BOARD IN SOUTH AFRICA.

South Africa is still ahead of many African countries in terms of its economy, its democracy and also the application of the law

READ THE REST OF AMIR'S STORY

Somalia is in turmoil, and that is well known, and when we see some of our other brothers and sisters here, like Ethiopians: they are not even free in their own countries. They can’t talk freely out of fear of being

killed. So in comparison, South Africa has one of the best-written

constitutions but implementation is always a problem.

For the Somalis in South Africa who have suffered back home, for the

youngsters whose education was disrupted, and who now face persecution in South Africa, it is like being caught between two hells.

But we believe in life after death. But the truth is Somalis in South

Africa have a lot of opportunities that we don’t have back at home,

despite the problems, the killing, the looting, the maiming, that we

face every, single day here.

So between Somalia and South Africa, Somalis have progressed here, some have furthered their education, while others have succeeded in business. We are not in the same state that the first Somali migrants were in 20-years-ago.

Although South Africa has ratified many treaties internationally and

in Africa, and also has its own law about the way migrants should be

accepted here, we also have to respect the locals, even when they are wrong. We are weak. So even when the Zulu King says all foreigners should leave, we know we can lodge a complaint with the South African Human Rights Commission, or we can criticize it in the media, but we cannot go that route because he has many followers and we fear reprisals and victimisation.

So we choose the route of dialogue, sitting with people, explaining to

them that we are not a threat to them, and at least we can say we have been successful, because our members are back in Soweto and trading.

But we have also learned through sitting at the table with South

African business representatives and government, that even if we are

naturalised South African citizens, we will still be treated differently; we will always be a foreigner. We have been called names that can lead to ethnic profiling, we have been accused of being terrorists.

We have found that yes, according to the Bill of Rights, the Constitution, the law, we are equal to South Africans and but on the ground we are not equal.

What needs to be clarified through better education that it a legal

requirement that foreigners have socio-economic rights here.

Analysis

Jean Pierre Misago

Researcher at the African Centre for

Migration and Society at the University of Witwatersrand

Al Jazeera:

What are foreigners supposed to do if justice fails them?

READ MISAGO'S RESPONSE

Some foreigners are now turning to illegal firearms for protection. We

have seen in January what happens when they use them. That action then legitimizes the violence we see.

So people say, “They are killing us,

it’s now self-defence, and we have to protect ourselves. We can’t allow people coming from outside the country to come and kill us in our country.”

This cannot be sustainable. Today it can be foreign nationals, but

tomorrow it can be somebody else. So our leaders must be very very

careful, they might not care because foreigners are not their constituency… [but] next time it’s going to be somebody else.

When violence makes political and economic sense, it’s dangerous.

Everybody can be an outsider somewhere. We are all outsiders, and we have seen signs when people march to say people coming from another area cannot get jobs here anymore, we should be getting jobs in this company because this is our area.

That’s my view, everyone should get

jobs where they born. It’s dangerous, it’s very very serious, I’m very worried because I don’t see leaders taking the issue seriously. They think it's foreigners, but its more than that.

It’s some section of the population deciding who has the right to live

where, and to live in our cities and enjoy the benefits they offer.

And that’s dangerous as I said because everyone is a foreigner

somewhere. We are all foreigners.

Michael Neocosmos

Professor and Director UHURU

Unit for the Humanities at Rhodes University

Al Jazeera:

Is there a solution to xenophobia in

South Africa?

READ NEOCOSMOS' RESPONSE

There are solutions but people have to understand there’s a different

way of thinking. The only way is people have to sit down and talk and

they not talking, there is no culture of talking there is a culture of violence.

So in those situations in where people have organised politically as defending themselves and attacking others, but to bring various people in the community together and talk. Its important to stress that in some places violence has not occurred around foreigners. And there are important reasons why this has often taken place its because where violence hasn’t taken place people are organised enough to unify the community around certain issues and bring people together to make the point that violence against

foreigners is no solution to anyone.

So this is possible, this idea of

talking and organising communally can take place at different levels

of our political society and that is what’s required. Unfortunately in

this country we don’t do enough talking.

No place like home

By Khadija Patel and Azad Essa

Photography by Ihsaan Haffejee

BY AL JAZEERA ENGLISH