BEYOND

THE BEACH

HOVER TO

NAVIGATE

of Yala National Park in Sri Lanka’s southeast corner, safari jeeps full of bleary-eyed Europeans, Russians and Arabs are bumping along potholed dirt roads in search of the park’s most elusive prize: the Sri Lankan leopard.

Eager eyes scan grasslands shrouded in morning mist, passing over Yala’s less exotic residents: peacocks, deer, crocodiles, boars, elephants.

A call comes in on the guide’s mobile phone. A leopard has been spotted in a nearby forested area, one guide tells another. The driver shifts into second gear to speed to the site before the leopard disappears into the trees. Passing jeeps make U-turns and follow the caravan, recognising the urgency of the lead driver.

He stops suddenly and points. There, sprawled in the canopy of a leafy tree, a leopard sleeps. Its face is tucked between two branches, hind legs dangling, spotted stomach heaving with the regular rhythm of cat slumber.

BEFORE THE SUN RISES OVER THE SEMI-ARID FORESTS

A cacophony of shutter snaps emanates from the jeeps. Satisfied nature lovers congratulate each other on their photographs of the exquisite animal. This, after all, is why they came.

Portraits of leopards and Sri Lankan elephants are splashed on travel brochures and websites beckoning foreign tourists to Sri Lanka’s many treasures. The Sri Lankan Tourism Development Authority has waged an all-out marketing blitz over the past few years, branding Sri Lanka “The Wonder of Asia” and hoping to cash in on one of Sri Lanka’s most commoditised resources: natural beauty.

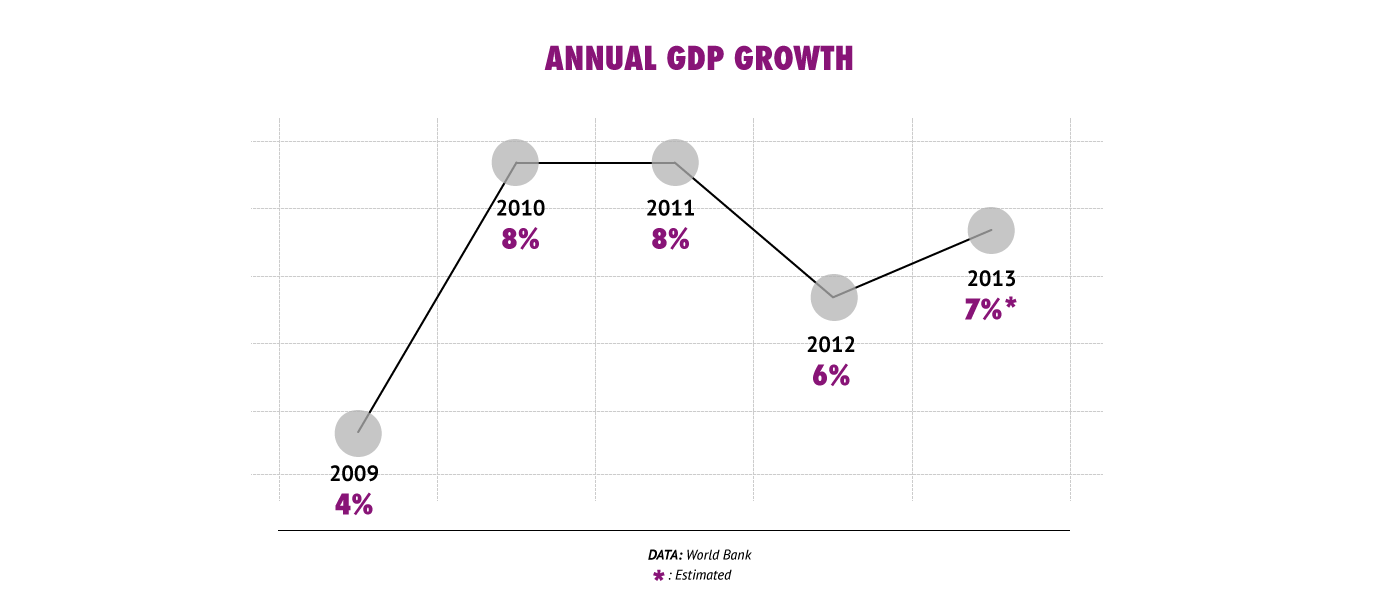

It seems to have worked. Tourism has returned to Sri Lanka - even to parts off-limits during the war to all but the most intrepid travellers. In 2013, 1.2 million tourists arrived in Colombo’s international airport; almost triple the number in 2009, according to government statistics. They are expecting 2 million in 2015.

Tourism has played a leading role in the growth of the economy, says Rumy Jauffer, the managing director of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau. In 2012, tourism brought over $1bn into the economy and employed 68,000 people. Another 95,000 people benefited indirectly as the dollars trickled down to craftsmen, taxi drivers, farmers and fishermen.

The return of tourism has also been a key indicator of stability for potential foreign investors who stayed away during the war, Jauffer added. He is proud that international hotel chains - Shangri-La, Movenpick, Hyatt, Sheraton, Marriott - are coming to or expanding their businesses in Sri Lanka. In an interview with Al Jazeera, Jauffer made a direct plea to other companies considering investment in an emerging market.

“If you’re looking at a destination with less rules, regulations, red tape and bureaucracy [for] investing your money, Sri Lanka is open for business,” Jauffer said.

the seaside of Sri Lanka’s capital city, a 42-floor skyscraper rises between the US and Indian embassies. Cloaked in green netting, the skeleton reveals nothing of the glamour arriving later this year in the form of Sri Lanka’s first Hyatt Regency Hotel. Construction crews toil in the tropical heat to build 475 guest rooms, 85 apartments, five restaurants, a spa, fitness centre and swimming pool for the millions of business and leisure travellers expected in the coming years.

Visible from many parts of Colombo, the Hyatt Regency construction site is emblematic of the post-war building boom that has mushroomed around the country. As Sri Lanka settles into the World Bank’s lower-middle-income bracket, financial planners are implementing an aggressive strategy to upgrade infrastructure, diversify industry and attract foreign investment.

COLOMBO’S GALLE ROAD, THE MAIN DRAG THAT RUNS ALONG

Lured by a welcoming government, a thriving economy and plenty of post-war potential, some international businesses are arriving: HSBC runs a call centre here; the London Stock Exchange outsources information technology operations to the Colombo-based company, MillenniumIT; Gap, Victoria’s Secret, Nike and Tommy Hilfiger all source from garment factories in Sri Lanka.

“We are able to project a certain atmosphere and environment to the rest of the world, so that others can come and do business in Sri Lanka in a fairly easy manner,” said Ajith Nivard Cabraal, the governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

China has spent nearly $4bn on infrastructure mega-projects, banking on a share of the peace dividend for Chinese business. A free trade agreement between China and Sri Lanka is expected to be finalised by the end of 2014.

Last year, China Merchants Holdings International opened a new $500m container terminal in the Colombo Port. Chinese banks have loaned Sri Lanka another $500m for a highway connecting Colombo’s airport to the city centre and for another airport in Hambantota, President Rajapaksa’s hometown on the southern coast.

And there’s more cash to come. “Now we see a pipeline of projects which will have a regular inflow of foreign investment coming in,” Cabraal said.

But some economists see this as a dangerous development.

“After the end of the war, we are heavily dependent on private borrowings from international capital markets at a very high interest rate,” said Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, principal researcher at the Jaffna-based Point Pedro Institute for Development. “These are costly for the public, not only for this generation, but also the future generation.”

that runs from the central tea-growing region of Kandy to the northern Jaffna peninsula. It has all the perks of a modern roadway: two lanes, a smooth surface, tri-lingual signs and rest stops. In good weather with light traffic, the trip only takes about four hours.

But for decades the road was impassable, bombed out and blocked by the Sri Lankan army and LTTE checkpoints as they fought for control of the Vanni region. When it reopened in December 2009, seven months after the end of the war, people could travel by road for the first time throughout their long-divided country.

The restoration of the A9 is perhaps the most important development project in post-war Sri Lanka. It connects, both literally and figuratively, the Sinhalese south with the Tamil north -- a connection vital for the reconciliation of two regions, two peoples torn apart by civil war.

IT’S EASY TO TAKE FOR GRANTED THE A9 HIGHWAY

Even before the road was reopened, the Sri Lankan government, aided by grants from overseas, set about rebuilding the war zone - pouring money and manpower into the country’s poorest areas.

New housing developments sprung up for the 300,000 who had been displaced. Electric grids lit up long-dark districts. Crops were planted where landmines once hid. Vocational training programmes were launched. Wells were dug; schools were built; railroad tracks were laid.

Today, the northern city of Jaffna is once again a bustling regional capital with modern amenities that mark the progress of peacetime, including its first stop light and a shiny new shopping mall. The transformation is widely acknowledged, even by the government’s toughest critics.

But despite the booming growth, job opportunities remain scarce in many smaller communities.

One major flaw of the north’s development is that it is centralised and controlled by the national government, according to Thurairasa Raviharan, a member of the Northern Provincial Council. The Tamil National Alliance, of which Raviharan is a member, won the majority of seats on the provincial council in a landslide victory in the September 2013 election.

Raviharan says local government should be given more power and resources to initiate development projects. He recently proposed the building of a broom factory in a village with 114 women-headed households near Mullaitivu, where the final battle was fought. The small factory would provide income for war widows with young children living in poverty.

The project is yet to be approved, Raviharan said, held up indefinitely by the governor, a retired Major General appointed by President Rajapaksa.

“This is a big hurdle for us,” Raviharan said of the central government’s bureaucracy. “We are not asking to bring down a company from abroad for our people. What we are asking for is the opportunity to use our own resources.”

Large, well-appointed cabanas open onto an impossibly-green manicured lawn rimming the white-sand beach of Sri Lanka’s northern coast.

Mesmerised by the turquoise water, a warm breeze and fresh mango juice, it is easy to forget the camouflaged, rifle-toting recruits patrolling the barbed-wire fence directly behind the hotel’s reception centre.

Ostensibly open to the public, this mid-range beachside hotel is located within an army base and is run by the Sri Lankan security forces. The reception staff, the cleaners and the assistant manager of food and beverages are all active-duty soldiers, albeit in civilian clothes.

Who holidays in an army base? Most of the guests are military families, who frequent a dozen resorts around the country run by the army, navy and air force.

HOLIDAY RESORT IS ONE OF JAFFNA’S POST-WAR BEAUTIES.

As well as resort hotels, the Sri Lankan security forces operate dozens of other businesses - from barber shops to vegetable farms and dog training. With free labour and cheap raw materials, these military stores undercut local entrepreneurs.

Though the economic impact is small, the psychological impact is considerable: unemployed, destitute war survivors see soldiers selling vegetables as a direct assault on their livelihoods.

With a bloated military that has not downsized since the end of the war, says Sarvananthan of Point Pedro Institute, the Sri Lankan government allows its idle soldiers to moonlight in the private sector.

“Ideally, we have to seriously think of downsizing or right-sizing the armed forces according to the needs of a post-war country,” Sarvananthan said. “We have one of the highest military to civilian ratios in the world, so that’s not conducive for the long run - for the country and democracy especially.”