BEYOND

THE BEACH

HOVER TO

NAVIGATE

was preparing for the next day’s service, cleaning the altar and polishing the wooden cross that hangs over the small chapel in the back of his home.

The Assemblies of God Church of Hikkaduwa was expecting around 100 worshippers from the usually quiet beach town on Sri Lanka’s southern coast. The pastor wanted his church to sparkle on Christmas.

Just before midnight, he heard a loud crack from the front gate. And then another, and another. Pop. Pop. Pop.

“We came out to check what has happened outside, and we saw two persons came and threw some heavy firecrackers to the front of my house,” the soft-spoken 42-year-old pastor recounted in an interview with Al Jazeera.

CHRISTMAS EVE 2013, AND PASTOR CHINTHAKA PRASANTHA

Another series of explosions, this time from the back of the house near the chapel, echoed through the alley, where the attackers fled on foot.

The firecrackers had damaged the walls and kicked up debris. Pastor Chinthaka picked up a broom.

“We had to clean again the church entirely,” he said, remembering that first assault on his church. There would be more.

a series of attacks against Muslims and Christians, part of what many have called a hate campaign led by a few hard-line Buddhist nationalists.

Groups such as Bodu Bala Sena, Sinhala Ravaya and Hela Bodu Powura see themselves as the protectors of Sinhala Buddhism, which they believe is being threatened by Sri Lanka’s ethnic and religious minorities and external forces.

Offering little evidence, they spin tales of Buddha statues being bulldozed, evangelical Christians forcibly converting the sick in their hospital beds, and Muslim women smuggling drugs under their abayas (traditional Muslim covering).

THE PAST TWO YEARS, SRI LANKA HAS SEEN

Egged on by radical monks’ fiery rhetoric, mobs of hundreds or thousands have run riot over mosques, churches and Muslim-owned businesses around the country.

More than 280 incidents of violent attacks and hate speech were documented by the Sri Lankan group Secretariat for Muslims in 2013 alone. Some attacks have been caught on news cameras, shocking viewers in Sri Lanka and abroad with incongruous images of behaviour unbecoming of Buddhist clergy.

on Assemblies of God Church in Hikkaduwa, two policemen visited Pastor Chinthaka to tell him Hela Bodu Pawura was planning a protest against his church the next day.

Undeterred, the pastor asked for police protection, warned his congregation and decided to go ahead with the Sunday service.

The next morning, Sunday, January 12, 2014, as police stood guard and local media flitted around, a group of hundreds marched towards the church. Children dressed in white led the way carrying traditional Buddhist striped flags, followed by around 30 orange-robed monks announcing their complaints through a loudspeaker. Residents joined along the sandy road, some as curious onlookers, others, sharing the outrage.

AFTER THE CHRISTMAS 2013 ATTACK

When they arrived, protesters swarmed the front gate of Pastor Chinthaka’s house and demanded the police shut down the church. One monk climbed onto the gate and rattled the bars, waving a fistfull of papers he said proved the church to be illegal.

“We will give our lives for the sake of our religion,” another monk shrieked, his maroon robe trembling as he gesticulated wildly. “Come, let’s go!”

The agitated mob ran around the back side of the house to the chapel, where the Sunday service had abruptly halted.

Pastor Chinthaka ushered his frightened congregation into the living room of his adjacent home – and as he bolted the door, they huddled and prayed.

Skull-sized stones crashed through the windows and hammered the corrugated-metal roof. Protesters overran police officers and breached the back gate. Climbing in through shattered windows, they tore signs off the walls and smashed them on the floor of the now empty church.

“There is no prayer - starting today,” a monk pointed threateningly to parishioners through a window.

Buddhika Wanniarachchi, a leader of Hela Bodu Pawura, said that protesters were provoked into violence. “Once we gathered around the AOG church they began to pray louder. Meanwhile a certain idiot at the church threw a stone at the protest march,” Wanniarachchi wrote in an op-ed in a local paper. “With that, a few [at] the protest march responded as we were treated.”

After about an hour, protesters left Assemblies of God and marched to the Cavalry Free Church across town for their second attack that Sunday.

When he was able to leave his house, Pastor Chinthaka confronted the police outside. “They said finally, ‘Pastor, we are so sorry,’” he remembered.

Despite the presence of police witnesses, incidents like these have rarely been prosecuted in Sri Lankan courts. Asked about the poor record of convictions Minister of Justice Hakeem shifts the blame onto the police.

“To a certain extent [there is] apathy by the law enforcement authorities,” Hakeem told Al Jazeera. “Particularly the police, which has to maintain law and order and to enforce the law, have been quite often seen to be standing by docile, without making useful interventions to prevent certain violent incidents taking place.”

In some cases, Hakeem said, police conduct half-hearted investigations - and rarely file reports strong enough to bring about a successful prosecution.

Perhaps because of that, President Rajapaksa recently announced the creation of a special police unit to handle such incidents. The 15-person unit, housed in the Ministry of Buddha Sasana and Religious Affairs, is tasked with investigating allegations of religious intolerance.

THE PRESENCE OF POLICE WITNESSES,

The head of Bodu Bala Sena, the most prominent and outspoken of the Buddhist nationalists, immediately applauded the president. General Secretary Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thero said in a press conference he had wanted a special unit to be established a year ago, according to the Sri Lankan news site Daily Mirror.

But others doubt the president’s motives. A group of Sri Lankan lawyers criticised the move as an evasion of justice and warned the unit could be co-opted by hard-line Buddhist groups who see threats around every corner.

“Establishing another police unit, in our view, will strengthen the hands of the extremists to use such a unit to intimidate minority religions and their devotees further,” JC Weliamuna wrote in a statement on behalf of the Lawyers Collective. “This unit will also be perceived as a license for ordinary police officers to shirk their legitimate responsibilities.”

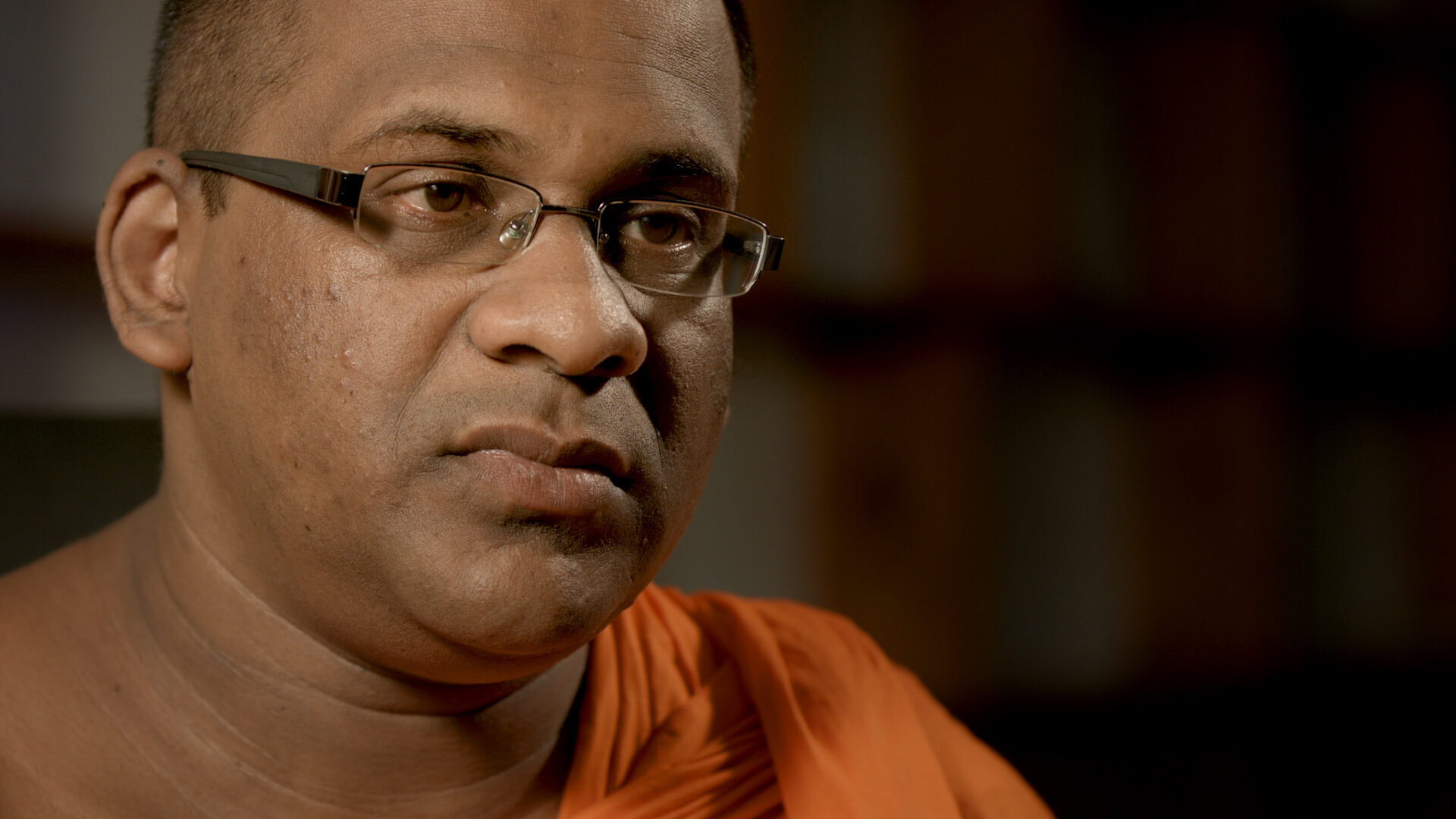

two of Bodu Bala Sena’s founders welcomed Al Jazeera into a modest classroom space they rent above an immaculate Buddhist temple on Colombo’s bustling High Level Road. The group’s lay leader, Chief Executive Officer Dilanthe Withanage served Sri Lanka’s famous tea and King Coconut Water. Bodu Bala Sena’s spiritual leader and General Secretary, Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thero, would come later, Withanage said, smiling.

Withanage explained with ease the reason he and five monks founded Bodu Bala Sena two years ago: Sri Lanka’s Sinhala Buddhists are under threat, he claimed, by “unethical” conversions, the lingering legacy of colonisation and rising Muslim extremism, both in Sri Lanka and globally.

He asserts that Sinhala Buddhists - who make up 70 percent of Sri Lanka’s population and control the presidency, the military and the state economic institutions - are actually, in terms of real power, a minority.

“With huge amount of dollars coming from Saudi Arabia to these Muslim leaders, these Muslim organisations [within Sri Lanka are] now more majority,” Withanage said. “Majority means not numbers, but power they exercise. That power comes from money. That power comes from external forces.”

THURSDAY MORNING IN APRIL,

Withanage scoffed at the suggestion that Sri Lanka is a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious society, as proclaimed by President Rajapaksa himself. He insists that Sri Lanka must identify as a Sinhala Buddhist country, despite the presence of four major religions and at least half a dozen ethnicities.

“Japanese say this is a Japanese country. Arabs say this is an Arabic country. British say this is a British country. Why 70 percent of Sinhalese cannot say this is a Sinhala Buddhist country? What is wrong with that?” Withanage asked.

As General Secretary Gnanasara, a tall, bespectacled, orange-robed monk, joined the interview, the topic turned to Sri Lanka’s Christians. Gnanasara grew animated when asked about the church attacks in Hikkaduwa.

“If you just put a cross there, you can’t call that a church,” he said, referring to Pastor Chinthaka’s Assemblies of God Church. “We requested the government to have a bill so that these unauthorised constructions and unauthorised practises of religious groups to be stopped by law.”

When the authorities didn’t comply, people understandably got angry, he said, defending the actions of Hela Bodu Pawura. Asked why these so-called illegal churches should be shuttered, Gnanasara compared their parishioners to rabid dogs.

It’s this vigilante attitude that prompted Dayan Jayatilleka, a former Sri Lankan ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, to term Bodu Bala Sena’s ideology “theocratic fascism.”

“What the BBS seems to demand is the right to behave as if Sri Lanka is a theocratic state in which the BBS are the ayatollahs and cultural police,” Jayatilleka wrote in a column on Groundviews, a Sri Lankan citizen journalism site.

Many of Sri Lanka’s secular intellectuals see the Bodu Bala Sena as part of a wider movement of religious extremism wielding increasing political power in Asia.

Gnanasara recently visited Myanmar to meet with Ashin Wirathu, the head of the right-wing Buddhist group 969, which is accused of inciting riots that have killed hundreds of minority Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar since 2012.

Some fear that Sri Lanka, still recovering from a bloody ethnic conflict, could face similar - if milder - strife.

In today’s anti-Muslim rhetoric, many Sri Lankans hear an eerie echo of the ethnic tensions that launched an anti-Tamil pogrom in Colombo three decades ago. For seven days in July 1983, rioting mobs went house-to-house hunting Tamils, dragging them into the street where they were burned alive and beaten to death by their neighbours. This horrific chapter in Sri Lankan history is widely seen as the spark that ignited the civil war and gave life to the violent insurgency of the LTTE and their growing separatist movement.