Parts of Antarctica are warming faster than anywhere else on the planet. Scientists want to know how this will affect the region, its abundant wildlife and the rest of the world.

The newly-formed Swiss Polar Institute invited an international team of climate scientists to spend three months - from December 2016 to March 2017 - circumnavigating the continent.

Al Jazeera's Science Editor Tarek Bazley joined them.

The Voyage

During the expedition the scientists will collect more than 10,000 samples and millions of megabytes of data.

A voyage like this has never been done before in one season and will visit many places that are too remote for other scientists to reach, including some sub-Antarctic islands that have never been studied.

Photo: Noé Sardet / Parafilms / EPFL

Leaving Port January 22, 2017

There's a flurry of last-minute loading before the Russian research ship, Academic Treshnikov, leaves the Australian port of Hobart. Fifty-five scientists from 22 countries are on board.

The three-month Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition, organised by the Swiss Polar Institute, will undertake 22 different experiments ranging from biology to climatology to oceanography.

Southern Storm January 24, 2017

The expedition encounters a fierce storm south of Hobart. Winds exceed 100km/h and waves are over 10 metres high.

The Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica is the only ocean that encircles the entire globe. It has some of the largest waves and strongest winds on the planet.

Changing Sea Ice January 27, 2017

As the temperature drops below 0°C, the ship slices a route through the sea ice. In the cracks between the ice crystals, there lives an ecosystem of algae and plankton.

These tiny creatures form the basis of an entire food web. As the Earth warms, the distribution of this sea ice around Antarctica is changing and scientists are concerned.

Minke Whales

For a time, the ship is escorted by a pod of Antarctic minke whales. These are the smallest and most abundant baleen whales in the world, with an estimated population of 500,000.

Over the 2016/17 southern summer, Japanese whaling ships killed 333 of these whales, part of a plan to kill 4,000 over 12 years.

Icebergs Ahoy

Near the coast of Antarctica we navigate around icebergs. Some are the size of a football pitch; others are tens of kilometres long. These icebergs have broken off glaciers or the ice shelf.

Most are now floating; towering more than 100 metres above the ocean surface while beneath the waves the ice drops down up to 500 metres.

Windiest Place on Earth January 28, 2017

This part of Antarctica is the windiest place on the planet at sea level. Pulling alongside the towering ice cliffs, the ship is whipped and buffeted by ferocious winds that sweep down from the high East Antarctic Plateau, bringing freezing dry air to the coast and driving snow and ice into the sea.

Touching the Glacier January 29, 2017

The Mertz Glacier runs from the East Antarctic Plateau down to the sea. When it reaches the ocean, a 32km-wide tongue of ice stretches 40km out over the water. Each year the glacier advances about 1km out into the ocean.

It delivers 10 billion tonnes of ice - the equivalent of 10,000 billion litres of fresh water - into the ocean each year.

Ice World

Antarctica contains 90 percent of all ice and 70 percent of all freshwater on the planet. The continent's ice sheet is more than 4km thick in places and if it were to melt, the world's oceans would rise by nearly 60m.

It remains unclear how this ice sheet is responding to global warming and how much it is contributing to sea-level rise.

Glacial Nudge

In 2010, an enormous chunk - around 75km by 35km - of Mertz Glacier broke off, after it was nudged by a large iceberg.

The researchers are eager to know what effect this had on marine life and whether such a dramatic event can be linked to climate change.

Credit: ESA

Hi-Tech Dive

The scientists launch a $5m hi-tech robotic submersible to explore the side of the glacier. They expect the ice cliff will descend hundreds of metres below the sea as a vertical wall of ice.

Equipped with HD cameras and water sampling technology, the submarine produces remarkable images.

Underwater Ice Cave

Instead of a vertical ice cliff, the team discover a huge underwater cavern. They drive the submarine into this vast ice cave and find that the seawater is warmer than expected and there is evidence of melt.

This is consistent with other findings in this part of Antarctica; warm ocean currents are now flowing further south, resulting in increased glacial melt.

Ice Plateau January 29, 2017

Every time it snows in Antarctica, a thin layer of ice forms. These layers trap tiny bubbles of air which become compressed and preserved in the ice.

By drilling ice cores scientists can reconstruct details of our past climate, including CO2 levels and temperature, reaching back over 800,000 years.

Photo: Noé Sardet / Parafilms / EPFL

Salt Bubbles

Seven metres beneath the surface the drilling team find bubbles they believe contain salty water. The discovery will give them valuable information about how warming ocean currents are affecting the ice.

There's little specific information about how the climate is changing, but the team hopes their ice cores will help fill in these gaps in our knowledge.

Helicopter Access

The expedition uses of two Bo105 helicopters to drop researchers and equipment onto some of the most inaccessible islands in the world.

The former police helicopters operate in extreme conditions, often landing on ice or on the deck of the ship in rough seas and violent winds.

During the expedition they fly for 107 hours and make nearly 500 landings.

Photo: Noé Sardet / Parafilms / EPFL

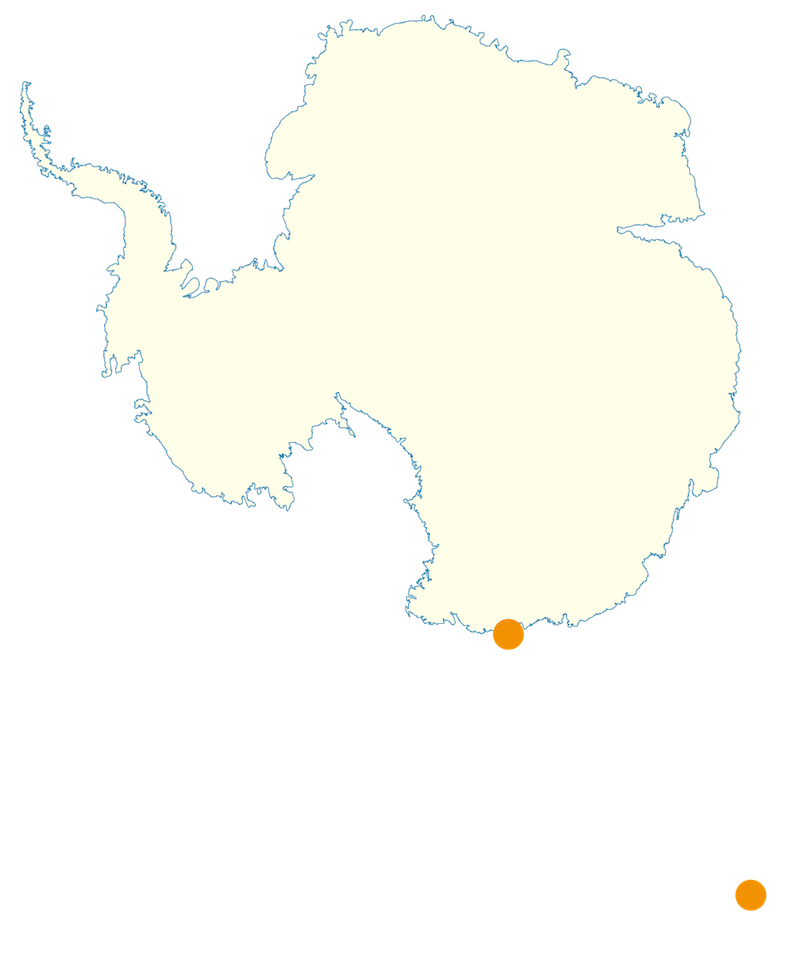

Balleny Islands February 3, 2017

The expedition travels east along the coast of Antarctica, arriving next at the Balleny Islands, a chain of three islands 2,000km south of New Zealand.

People have landed on these heavily glaciated volcanic islands fewer than 30 times since they were discovered in 1839.

Ice and Rock

The Balleny Islands consist of three main islands: Young, Buckle, and Sturge. They are all roughly 30km long and 5-13km wide.

The islands are locked in ice at least 10 months each year. Most of their coastline is a continuous wall of ice and rock reaching hundreds of metres up from the sea.

Flyby Survey

There are no detailed maps of the Balleny Islands, so it is decided to survey them from the air.

A high-definition stabilised video camera is mounted on the side of the helicopter and over the next two hours we fly at a height of 1,000 metres; the first ever flyby survey of these remote islands.

Fan-like Glacier

The Balleny islands' glaciers appear to tumble into the sea from the top of the islands, forming unusual fan-like shapes.

The photographs and videos will later be used as part of a project to construct a 3-dimensional map of the islands.

Photo: Noé Sardet / Parafilms / EPFL

Sabrina Island Penguin Survey

During the aerial survey the team fly over a small scrap of land called Sabrina Island. Here algae tint the snow green and there are signs of penguin tracks.

The island is an important breeding spot for Adélie and Chinstrap penguins. Flying low over the nesting sites we take super-high resolution images that will later used to calculate the number of birds in the colony and assess its health.

Photo: Peter Ryan

Brittle stars

Brittle stars or ophiuroids are closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their five long, whip-like arms which can grow up to 60 cm in length. There are more than 2,000 species of brittlestars.

Sea mouse

Sea mouse, or Aphrodita, is a type of marine worm. It lives on the ocean floor and is covered in a dense mat of hair-like spines. These are normally dark red but can flush green and blue as a warning to potential predators. Sea mice can grow to 30 centimetres in length.

Photo: Noé Sardet / Parafilms / EPFL

The Ross Sea

The ship travels further east toward the Ross Sea. In this area two violent and opposing weather systems and currents meet, resulting in volatile and stormy seas and strong and unpredictable winds.

The Ross Sea's nutrient-laden water helps support abundant plankton blooms. This makes the area rich in marine fauna, and home to at least ten mammal species, six bird species and 95 fish species.

Scott Island February 6, 2017

Five hundred kilometres off the Antarctic continent, Scott Island is one of the smallest islands the expedition will visit. It is the size of five football pitches and just 54 metres high.

The volcanic island was discovered in 1902 and named after the British Antarctic explorer Robert F Scott.

Photo: François Bernard

Sampling on Land

Scott Island is too windswept for seabirds to nest, but lichen and moss grow in the cracked volcanic rocks.

The scientists take samples to find out if they harbour life. This will give them an idea of how these animals have coped with climate change in the past.

Weather Station

Scott Island is so low-lying that storm waves wash over its barren rock and ice-covered top. It is also locked in sea ice for most of the year.

An automatic weather station was maintained on the island between 1987 and 1999. It recorded an average summer temperature of below 0C. In winter, it was down to -40C.

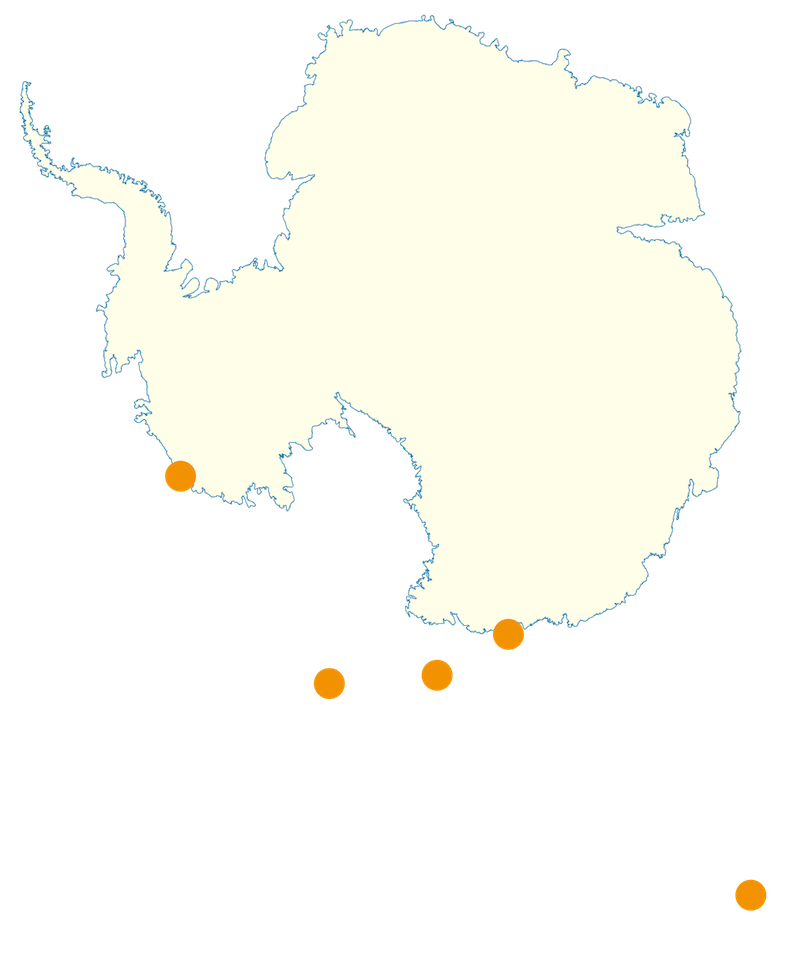

Mount Siple February 11, 2017

Mount Siple is one of Antarctica's tallest and most isolated volcanoes, rising more than 3,110 metres above sea level.

It is believed to have last erupted about 12,000 years ago. No one is known to have climbed to its summit, making it one of the most prominent unclimbed mountains in the world.

Penguin Landing

Mount Siple is normally locked in sea ice, but clear conditions and open water give the expedition a rare opportunity to access the area.

We find large number of Adélie penguins on the beach and from their numbers, it's clear there is a breeding colony nearby.

Penguin Rookerie

The scientists are flown to a rocky outcrop on the side of Mount Siple. Here, Adélie penguins are nesting.

Less than one percent of Antarctica is ice-free, making a place like this prime real estate for nesting birds. Surveying populations of penguins gives scientists an indication of the health of the Southern Ocean.

Colony on the Move

East of Mount Siple, the Antarctic Peninsula is warming faster than any other place on the planet.

Scientists have noticed that Adélie penguins here have abandoned their nesting sites and are moving south, perhaps in search of colder places to nest. Other more resilient penguin species have taken over these rookeries.

Plant Life

Antarctica is almost entirely covered with ice and snow. This means that only a few plants can survive.

There are no trees or shrubs and only two species of flowering plants. There are around 100 species of mosses, 25 species of liverworts, 300 species of lichens and about 20 species of microscopic fungi.

Photo: Noé Sardet / Parafilms / EPFL

New Mite Species

Only a few tiny invertebrates are able to live on Antarctica all year around.

The largest is a wingless midge, which grows up to a length of 12mm. Tardigrades, or water bears, are the most resilient. They can survive extreme cold and up to 30 years without food or water.

Mites are the most common invertebrates found on Antarctica; inside a sample of lichen the scientists discover a specimen they believe is a previously undiscovered species.

Light Night

At this time of year, at such at such high latitudes (74 degrees S), it doesn't get dark at night. Instead, there's a long and spectacular sunset.

The sun only brushes the horizon and as it does, it paints the ice and ocean in spectacular colours.

Peter I Island February 16, 2017

The expedition's last stop in Antarctica is at Peter I Island, to the west of the Antarctic Peninsula. Poor weather and thick sea ice prevent any attempt to go ashore.

The ice-covered island is 11km by 19km, with its highest peak at 1,640 metres above sea level. There is little life on the island apart from seabirds and seals.

Crabeater Seals

On the ice around Peter I Island, we see hundreds of crabeater seal, the most abundant seal species in the Southern Ocean, with an estimated population of 15 million.

Their success as a species comes down to their specially adapted teeth that allow them to strain seawater to catch krill. They are also able to dive down to 250 metres and can grow up to 400kg in weight.

Underwater World

Despite being cold - between 3C and -1.5C - the Southern Ocean is one of the most productive on the planet.

This is in part because it contains vast populations of tiny phytoplankton. Globally, these microorganisms produce half of the planet's oxygen. They also form the basis of the entire marine food web.

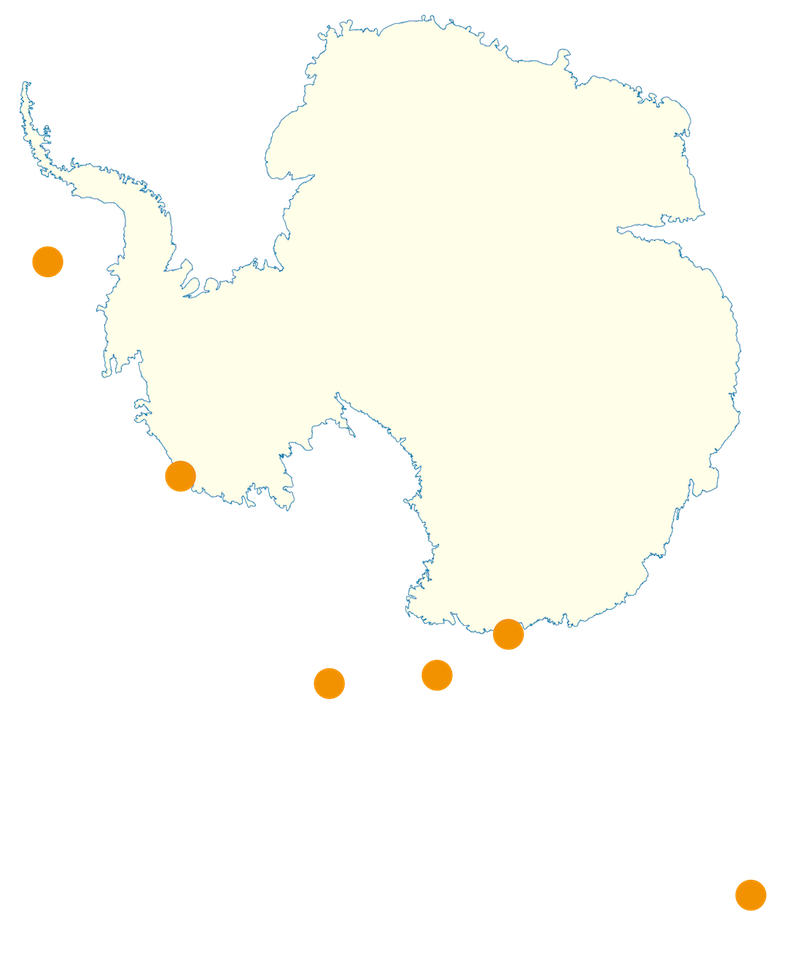

Diego Ramírez February 20, 2017

One hundred kilometres west of Cape Horn, Diego Ramírez is home to more than a million birds and a few Chilean naval officers.

The islands are an important nesting site for a number of seabirds, including the black-browed albatross, shy albatross, grey-headed albatross, rockhopper penguin, and southern giant petrel.

Peat Samples

In much the same way the rings of a tree trunk can be used to tell the story of its growth, samples from peat bogs on Diego Ramírez will help scientists build a detailed picture of the climate in the past and how it has changed.

During the month-long leg of the voyage scientists have taken more than 10,000 samples and recorded millions of bytes of data - all in pursuit of a better understanding of climate change.

Patagonia February 21, 2017

On the final day of this leg of the voyage the expedition sails through the fjords of Patagonia.

It's a landscape shaped during a very different, ice-bound, period in Earth's history and a reminder that climate change has taken place before; but never at such a rapid pace, nor as a result of human activity.

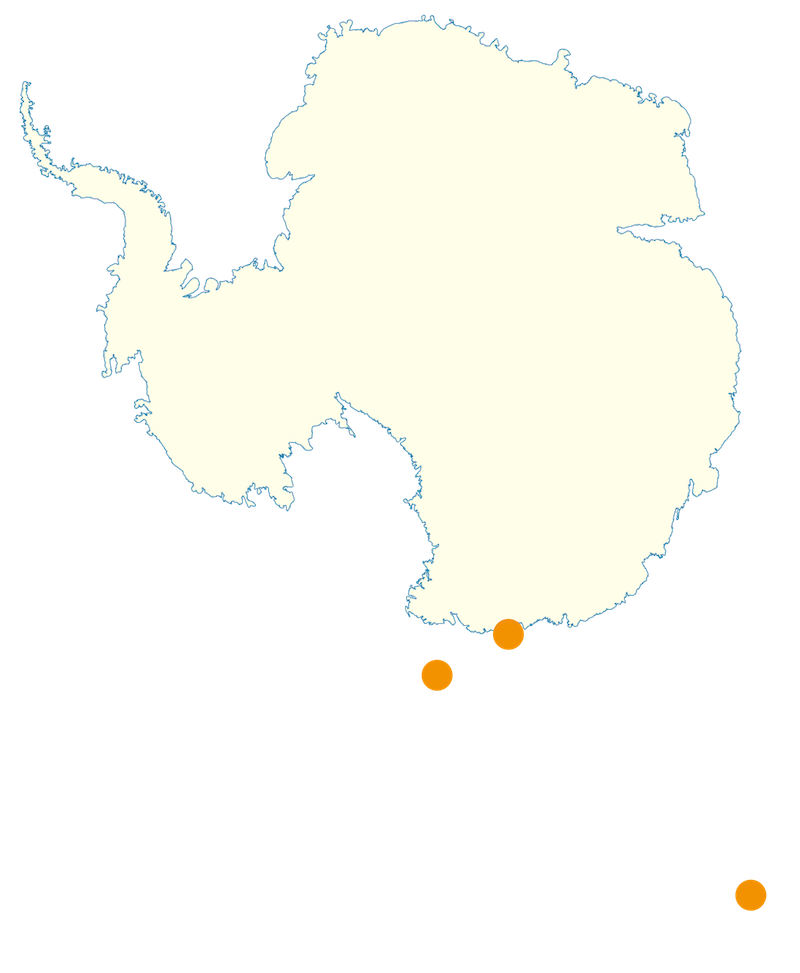

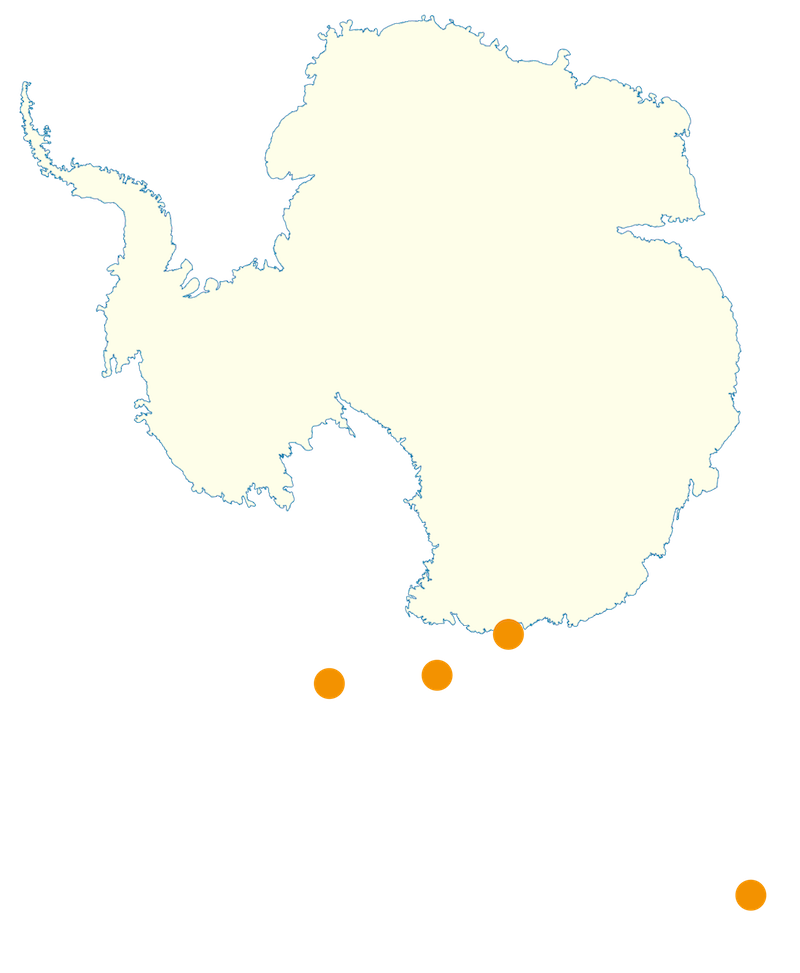

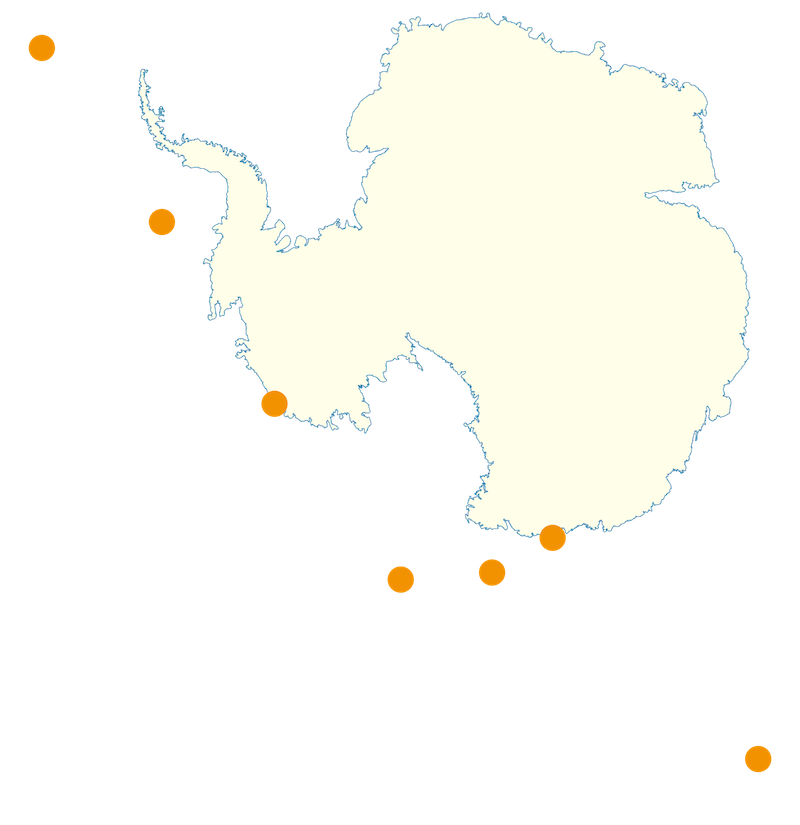

Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition

The scientists taking part in the 2016-17 Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition travelled to some extraordinary and remote locations.

They now hope the samples they have taken will help fill in gaps in our knowledge and this will give us a better understanding of the impact of climate change on the continent and its diverse wildlife, and ultimately how this will affect the rest of the world.