Dumsor [doom-sō], noun.

1. A period of time in which darkness is more prevalent than light.

Dumsor:

The electricity outages leaving Ghana in the dark

By Caterina Clerici, Marisa Schwartz Taylor and Kevin Taylor

The line outside Papaye is long, as on any other muggy night in Accra, the capital of Ghana, but the place looks closed. Anyone who hasn’t been to the first chain restaurant in the country before would have a hard time understanding what people are queuing for.

All the lights are out in the Abeka neighbourhood, including the neon yellow sign advertising ‘Ghana’s Total Food Care Company,’ a shining symbol of Ghana’s middle class - when there is electricity.

As the management struggles to turn on the generator, a flash of light reveals two huge rooms packed with customers eating fried rice and chicken. Then, after a few seconds, all that’s left are silhouettes in the dark.

Accra, Ghana: The lights are out at Papaye Restaurant in the Alajo neighbourhood of Accra. The restaurant is packed and customers eat fried rice and chicken in the dark as management struggles to turn on their generator.

While the small West African nation is praised as one of the most stable African democracies, the state of its economy has not been as impressive amid a sharp currency depreciation, a deteriorating macroeconomic imbalance, rising inflation, and a deepening energy crisis.

The 159 days of blackout that the country experienced last year is the most striking sign of this crisis. Entire neighbourhoods switch off in an instant. Without a public load-shedding schedule, the patchwork electrical grid often leaves one side of the street in darkness while those on the opposite side have light.

The entirety of Sub-Saharan Africa produces less energy than South Korea - despite having more than 18 times its population. Compared to the rest of the continent, Ghana has one of the highest rates of access to electricity.

However, in many instances the demand is often too high to be met. The breakdown of machinery used to generate electricity - often faulty from the continuous interruptions of energy, - lack of fuel to power them, or issues in distribution, are only some of the reasons for the shortages.

1

Energy generation

Akosombo, Ghana: A view of the Akosombo Dam from the Volta Hotel Akosombo. The Akosombo Dam has been Ghana's main source of energy since the 1960s, however, due to recent droughts, it has been operating at minimum capacity.

January 22, 1966, marked the start of a new era for Ghana. Modernisation was supposed to come in the shape of the 1,030 megawatt-generating Akosombo hydroelectric dam inaugurated that day.

The giant Volta River Project, built in collaboration with the United States and with the support of the World Bank, would be able to produce vast quantities of cheap power, boosting the creation of a modern, industrial state - at least in the development dreams of the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah. More than 3,000 people were employed - and over 80,000 people displaced - to make room for the hydroelectric project, which formed the largest man-made reservoir in the world, Lake Volta. For Ghana, the dam came to embody the idea of nationhood itself.

"The abundant supply of electrical power will bring light to thousands of homes in the countryside where darkness now prevails," said Nkrumah during a speech presenting the Volta River Project to the National Assembly, on March 25, 1963.

According to Nkrumah, the Volta Project was supposed to become one of "the new ‘places of Pilgrimage’ in this modern Age of Science and Technology," an inspiration for the rest of the continent and the world alike.

"It will make available power practically at the door-steps of businessmen and entrepreneurs in urban areas and offer them a powerful stimulus for the modernisation of existing industries and the development of new ones."

But today, the dam’s six turbines are struggling to produce 67 percent of the country’s power — as they used to in 2012, according to the World Bank’s most recent data.

Because of a drought - very likely attributable to climate change - the water from the lake and its emissaries is at the lowest possible operating level. At the same time, over the past 50 years since Akosombo was built, electricity demand in Ghana has witnessed a skyrocketing growth of over 300 percent, reaching a peak of 1126.82 GWh in 2015.

Akosombo, Ghana: The Akosombo Dam. The dam was operating at its lowest capacity - 240 feet - on this day.

Dumsor affects everybody. Families and businesses, hospitals and universities, factories and shopping malls. The private and the public.

"It reduces productivity: the fan is off and you may have to go out of the office when you don't have a generator. Or you have to go and buy a generator, and buy diesel or gasoline for the generator," said Ishmael Ackah, head of policy at the Africa Centre for Energy Policy and a lecturer in Economics of Energy at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi. "So it increases the cost of operation."

Compared to the rest of the continent, Ghana has one of the highest rates of access to electricity. In 2012, it ranked second only to South Africa, as shown by the latest available World Bank data. But the blackouts still persist.

"Any time there is a shortage of power - either peak load or off peak load - people see that it is coming from our system, because we are the interface between the generators and transmitters and the customers," explained Erasmus Baidoo, the Ashanti regional public relations officer for the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG).

"But most of the outages were not caused by ECG at all. It was purely generation issues. Anytime there was a shortage in generation it affected the distribution."

In Ghana, the energy sector is made up of three main groups - generation, transmission and distribution, Baidoo explained. The generators consist of the Volta River Authority, which operates Akosombo Dam as well as several thermal plants, and a few private contributors.

The Ghana Grid Company then takes this power and transmits it to the ECG - Electricity Company of Ghana (and NEDCO in the North) - which distributes electricity at a consumable wattage to businesses and residential customers. Sometimes, when power is limited, the hardest part is choosing who gets it, and who doesn’t.

"We have specialised or sensitive customers among the customer list," continued Baidoo.

Among ECG’s customers in the Ashanti region, the country’s most populous, are hospitals, the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, which has over 50,000 workers including students and lecturers, Ghana Water Company’s booster station, not to mention the police, the military, and prisons.

"[After] you give to all these areas or sectors you have none left."

2

Personal stories

Every morning, Kumasi wakes up early to the sounds of bustling marketplaces, like Asafo market. The streets of the surrounding area are packed with people – butchering cow legs, lifting bags of charcoal, selling fried doughnuts, or running to catch the tro-tro that will take them to the other side of the city, after spending a few hours stuck in traffic and heat.

"Sometimes we come and the light is out. The only thing you hear is that it will be fixed. You have no option… you have to throw [the meat] away so that you don’t have a problem with the Food and Drug Authority."

Grace Ogrey, the owner of Metwe ma Jesus cold store at Asafo market, sells frozen chicken. In a nation where not every restaurant and business – let alone every household – has a freezer, cold stores are a pillar of daily life. But the line outside the Metwe ma Jesus cold store is nowhere to be seen.

"Before God and man, I can tell you that the dumsor has greatly affected our business.

Initially, the electricity company had a schedule for us. But it got to a point that there was no schedule and the light just went off unexpected and unannounced," Ogrey said. "This was one of the best jobs to do in this country, because the meat was frozen perfectly and we were making decent money."

Ogrey said that sometimes the store’s freezers break so often they don’t make any money, and the little they’ve made goes into repairing the machines.

Auntie Grace Ogrey, who has a cold store and sells frozen chicken in Asafo Market.

A couple of streets down from the market and right opposite the ‘British Pub,’ a chop bar where two women were pounding plantains and cassava into a white dough for fufu with light soup, ‘Emmanuel Printz’ printing press was buzzing with customers. They were printing anything from newspapers to funeral programmes and posters, and the floors of the small shop were covered in paper cut outs.

"To be honest with you, due to the dumsor we nearly closed down," said Kingsley Adjei Jeffrey, reactivating the printing machine and speaking loudly above its humming.

"Not all of the companies you see around here have standby generators or power plants for production. We lost out on so many jobs and contracts," he added. "A few printing presses that had generators took over the jobs, and this brought so much pressure on us."

Jeffrey explained how the load-shedding era had brought along a very different routine, together with constant worries and exasperation. Once the lights came back, the employees of the printing press would have to take care of the backlog, which meant working at whatever time the lights returned – day or night.

"Or sometimes, the customers might not even bring anything because there is no light so you just have to hang around doing nothing."

At Kaneshie Market in Accra - one of the capital's busiest commercial and transportation hubs - evening commuters navigate a maze of buses, jollof rice vendors, DVD salesmen, pastors and anyone else you could imagine amid an orchestra of honking taxis and whirring generators.

"From morning until 4pm, we don’t care because you can see with the sunlight. But after 5pm, it becomes difficult for us to see when we are selling to customers," said Faustina Sapeh, a food vendor at Kaneshie market.

She was selling dried fish and kenkey, sitting at a stall in the middle of a taxi rank turned open-air church for a few dozens impromptu night worshippers. A flashlight was attached to her stand: the streetlights are rarely on along the highway that runs from Kaneshie Market all the way to Kwame Nkrumah Circle, despite it being one of the main arteries in Accra, a city of over four million.

"Sometimes, people buy food with counterfeit money. Because it’s dark, we are not able to see it until we get home. So the light has really affected our business"

- Faustina Sapeh, Kenkey vendor, Kaneshie Market

Faustina Sapeh sells kenkey and dried fish at Kaneshie Market at night. She rents a flashlight daily since the streetlights in the area don't work.

3

Dumsor on Social Media

Kumasi, Ghana: Young women take photos at Rattray Park, Kumasi's newest luxury attraction. The park has a massive water fountain with a lightshow that consumes more energy and water than some neighbourhoods.

The lights were out in Ayeldu, a small village in central Ghana, but the faces inside the chief’s house were lit up - by smartphones. The majority of Ghanaians have mobile phones, which means access to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the world at large.

When the lights go off at the hair salon right before the curling iron is turned on, Ghanaians turn to social media to vent their frustration. A black square appeared on Instagram recently with the caption "this was supposed to be a selfie. #dumsor"

Explore the world of dumsor through Ghanaian social media below.

#Dumsor on Social Media in Real Time

4

Alternative Solutions

Tema, Ghana: An exterior view of the Karadeniz Powership Aysegul Sultan in Tema Harbor. The powership was brought in from Turkey and can produce 250MW of power, directly connected to Ghana's grid. It is, quite literally, a floating power plant. This was seen as an emergency solution to Ghana's power crisis and was quite controversial in Ghanaian politics.

In February 2015, President John Dramani Mahama, then entering his third year of elected office, delivered his State of the Nation address, promising to ‘fix this energy challenge.’ Ghana, he remarked, had already witnessed a similar dumsor situation in 1983, 1998 and 2006/7.

By the end of the year, the government had established an energy sector levy and an energy debt recovery levy, commissioned Kpone Thermal Power Plant and paved the way for the most bizarre emergency solution to energy inefficiency to have yet docked – literally – to Ghanaian soil.

The Karadeniz Powership Aysegul Sultan power barge is a floating power plant with a surface bigger than a football field and six turbines generating an average of 210 MW, around 11 percent of Ghana’s total energy supply.

The power barge moored in Tema harbour on November 27, 2015. Once its on-board high voltage substations were connected to the national grid, it immediately started delivering power -10 days after arrival.

It would have taken much longer to build a plant and put it on the ground, argued the Turkish and Ghanaian personnel of the barge during a tour of the facility. Plus, it’s cheaper than thermal plants: it runs on heavy fuel oil, which costs less than light crude oil, and has the option to run on natural gas in the future, depending on supply and fluctuation in international market prices.

Ayeldu, Ghana: an old man looks out at the village at dusk, when the lights finally returned after being out all day.

The first of its kind in Africa – Karadeniz, the Turkish company behind the project, also has powerships in Iraq, Lebanon, Indonesia, and recently in Zambia. The "Power of Friendship for Ghana" project was met by a mix of scepticism by Ghanaians. Before its arrival, a radio station said the barge didn’t exist and called it a phantom ship. After it started operating, people argued that the government would spend too much money on a temporary fix instead of building more long-lasting and sustainable energy sources.

According to the company though, it could save Ghana $120m a year, and another power barge is expected to call the country home next September: Karadeniz and the Electricity Company of Ghana have already a signed a 10-year contract, expecting the two powerships to produce 450MW of electricity.

"A day after Independence Day, still celebrating and having a good time?" Lexis Bill asks into the microphone, surrounded by a fortress of screens and tangled cables in the recording studio at Joy 99.7 FM in Accra.

The radio presenter expects no answers. Every day, his show ‘Drive Time’ keeps Ghanaians company from 3 to 8pm.

"Well here’s something interesting: yesterday I was driving through town and I realised some parts didn’t have lights and some other parts did!" Bill continues. "We are excited that dumsor is getting better, now we are getting more power even though we are paying higher. So my question for you now is – would you rather have more light and pay more, or less light and pay like you were paying one year or two ago?"

The arrival of the power barge coincided with the ‘end’ of the dumsor era, officially called in late December 2015 - in time for the Christmas holiday. Power cuts have since occurred less and Ghanaians have been paying for slightly more stable electricity — sometimes.

"People try to cheat the system," said Baidoo, ECG’s Ashanti regional public relations officer. "They rather bypass the meter or they find a way to tamper with the meter so that instead of recording very accurately, the meter will not record at all. Or it will be giving wrong figures."

According to Baidoo, only around 40 percent of ECG’s customers pay their bills voluntarily, without any prompting. Hence the company – which counts millions of dollars in debts, owed by the government - has had to come up with a way to chase customers to pay bills for a service that has been intermittent, at best, for years: prepaid metres. For now though, the solution is bringing more questions than answers.

"What about the 60 percent [of customers that don’t pay]?" Baidoo asked. "Are you going to arrest everybody? Will you deny them power because they have not paid their bills?"

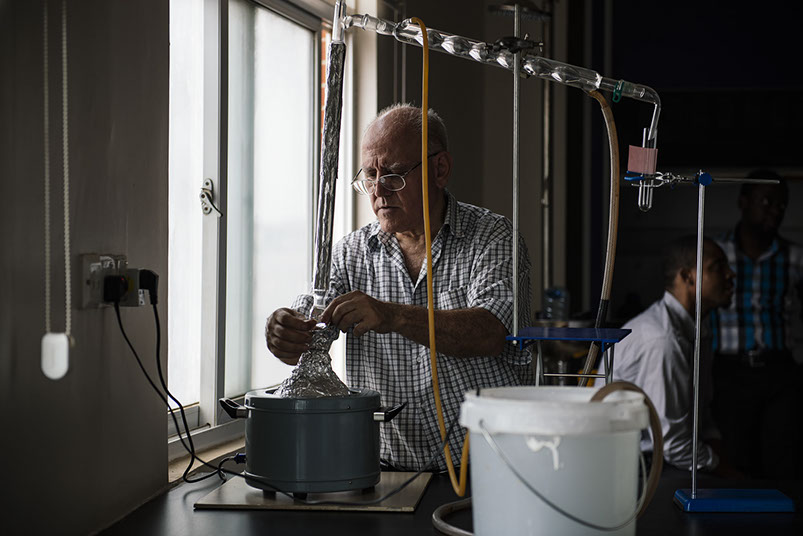

A similar question — how to get cheap energy for everyone, even those who cannot afford to pay those bills— is on the mind of Raymond Ayayee and Daniel Nashief, as they watch a golden liquid boil over in a separatory funnel, smoke twirling out of it.

"Tyres can become diesel. I can get carbon black, which can be used in ink and paint. I can get heating gas… and I can get the oil, which can be used as substitute to diesel. Which is ok," rambled Nashief, a biochemist.

Workers collect discarded plastic waste, mostly water sachets, to melt into fuel

Daniel NaShief's assistants begin the process by melting the plastic waste

Daniel Nashief checks the temperature on his plastic to fuel system, during the beginning stages

Nashief and his assistant, Evans Sackitey

The byproducts of Nashief's process - including naphtha, gasoline, kerosene, diesel and wax

Ekue Aholou Akodo examines the finished diesel product

Nashief works in the lab at The Africa Institute of Waste Management

One of Nashief's assistants monitors the temperature during the final stage of production

4 - 8

<

>

The warehouse where the two set up their DIY open-air lab is underneath the African Institute of Waste Management in East Legon. It’s on the opposite side of Accra — and a world away - from the burning tyres of ‘Sodom and Gomorrah,’ the digital dump that has made the Agbogbloshie slum world famous. Nashief and Ayayee are also burning tyres, and all sorts of plastic waste, but with a goal: to produce fuel from plastics.

Since the duo met two years ago, they have successfully converted plastics — mainly water sachets, which can be found discarded on every street of the country — into naphtha, gasoline, kerosene, diesel and wax with the help of a distillation process, a secret ingredient (the catalyst) and a lab mouse that gets quite jumpy when it smells chemicals that shouldn’t be there.

The petrol produced from plastics can be used in generators or in cars, while kerosene lights up lanterns and gas cookers in the villages when the electricity is out.

"The way I produce doesn’t cost much," continued Nashief, "One litre of kerosene today is around 2GHS and I’m able to produce one litre of kerosene for 1.70 GHS. That is something for the village people. They will appreciate [it]."

A little over an hour outside of Accra, and protected by a gate and a handful of armed guards, is a dark blue field, stretching as far as the eye can see. It’s made of 89,760 solar panels.

The BXC Solar Plant in Ghana’s Central Region is the largest functioning solar farm in West Africa. Owned by a Chinese company, it started operating in February 2016, after two years of construction. It produces 20 megawatts of power, largely contributing to Ghana’s ambitious plan to reach a 10 percent renewables milestone by 2020.

"We have a lot of sunlight, so this will be good for us," said Michael Annang, an electrical engineer and one of the eight permanent staff on site. "The maintenance is the only problem: you have to constantly clean [the panels] from dust and make sure the weeds don’t grow there."

"The solar project is cleaner power. This project, we can keep 25 years," says Luan Ye, BXC’s Chinese engineering manager. "The panels will help the country change to cleaner power. After the water finishes and the oil finishes, how will you get the power?"

The country’s transition to solar has started slowly, making the objective of a 10 percent slice of energy resources coming from renewables by 2020 nothing more than wishful thinking. On a smaller scale though, the idea has taken root in many places where dumsor switched off everything but an entrepreneurial spirit.

"We went to YouTube and we saw how things were built," explains Idrissu Musah, a tutor and the head of the social studies department at King’s College complex in Kumasi. "Then we went to town and asked the price of these panels, the gadgets."

Standing on a small terrace on the rooftop of one of the school buildings, he points at a dusty solar panel dominating the view, and connected to an inverter by a bundle of cables. Musah was among a handful of teachers and school administrators who argued that one of the possible ways to take on the ongoing energy crisis could be using solar power.

During dumsor, the school’s over 2,000 students weren’t able to go to "prep" (preparation for the next day) and do their homework at night, because there were no lights. When the power was off, the hours in the computer labs were wasted. The school was paralysed and the administration knew they had to find a solution, but installing solar panels seemed too expensive —until Internet tutorials made it possible.

"We realised that if we built it ourselves we could beat down the cost."

The school currently derives almost 20 percent of its electricity from solar power and is planning to reach 90 percent within the next three years. By using a photocell, the inverter takes over as soon as the electricity goes off, and no one even notices. The electricity bill has been reduced, and no one has an excuse to avoid doing their homework anymore.

"If you are able to implement it in those schools in the long run it will be very cost effective. Now the schools are using big generators or plants that run on fuel, and sometimes students are made to pay the fuel costs," continued Musah.

"A time may come, even when there are light offs [that] the schools don’t suffer."

Back to top

This web documentary was developed with the support of the Innovation in Development Reporting Grant

program of the European Journalism Centre (EJC), funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Producer: Kevin Taylor

Photography: Marisa Schwartz Taylor

Text: Caterina Clerici

Design: AJLabs

Videography: Caterina Clerici and Marisa Schwartz Taylor

Video editing: Caterina Clerici

Graphics: Marisa Schwartz Taylor

Drone Pilot: Kevin Taylor

Translation: Kevin Taylor

Additional Reporting: Fentuo Tahiru

Fixers: Kudjo Lartey and Djamani Dankwah