Stepping out into Times Square in New York City, Otis Johnson is struck by the overwhelming number of people. Everyone seems to be walking quickly with blank faces and wires in their ears.

He’s confused. Being completely removed from society since 1975, Johnson thinks he’s entered a dystopia where everyone has become a secret agent wearing wires. The Steve Jobs era has completely passed him by.

In August 2014, Johnson was released from prison after serving a 44-year sentence for the attempted murder of a police officer. He went to jail when he was 25 years old. By the time he came out, he was 69.

Johnson’s release date was originally scheduled for earlier, but he ended up serving an additional eight months at the age of 69 for a juvenile shoplifting charge he received when he was 17.

Johnson represents a very small set of people in the United States. In 2013, approximately 3,900 inmates were released from US prisons after serving at least 20 years, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. That is less than 0.7% of all state prisoners released that year.

Meanwhile, about 6,000 federal prisoners are to be released in November 2015. The United States Sentencing Commission has implemented early releases for some drug offenders.

Prison reform has become a major focus point for the White House during US President Barack Obama’s final year in office. In a recent speech at Rutgers University, he highlighted the need for prisoner re-entry programmes focused on education, job training and housing, and recounted success stories of formerly incarcerated citizens who had escaped the cycle of recidivism that plagues many inmates.

“It’s not too late,” Obama said. “There are people who have gone through tough times, they’ve made mistakes, but with a little bit of help, they can get on the right path.”

But while initiatives to reduce the sentences for drug offenders and nonviolent crimes are under way, the elderly prison demographic is beginning to emerge as another group in need of legislation reform.

In 2014, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the overall US prison population fell to its lowest level since 2005.

However, the data also shows that from 1999 to 2014, the number of state and federal prisoners aged 55 and older grew by 250 percent, while those younger than 55 grew by only 8 percent. Elderly prisoners were only 3 percent of the total prison population in 1999. But by 2014, that number had grown to 10 percent.

The justice department sees the nearly quarter-million elderly prisoners as a top issue year after year, not least because housing and feeding an aging population is expensive. But the number of senior citizens released from prisons remains small.

Bipartisan agreement on anything is rare these days. But there’s consensus on mass incarceration. New sentencing guidelines could result in 46,000 of the nation’s approximately 100,000 federal drug offenders qualifying for early release. Elderly inmates could be the next wave of ex-convicts to be reintroduced into society.

But former prisoners like Johnson, who was released after decades of isolation, encounter obstacles that transcend those the current, younger, wave of ex-convicts face. Their needs are drastically different. Mental health issues, coping strategies and other side effects of long-term imprisonment come into play.

Marieke Liem, a researcher at Harvard Kennedy School interviewed prisoners who have served decades behind bars. She said there is a large lack of resources for those coming out after serving long sentences.

From being introduced to modern technology, to navigating public transportation, to opening a bank account, to making simple life choices like what to buy at the grocery store, Liem says many of these kind of ex-prisoners struggle due their lack of agency.

“Prison decides when lights go on and when they go off,” Liem said. “Every moment of the day is scheduled. When you have been in the prison system the majority of your life, how can you be expected to function as a member of society? And make a plan?”

Upon release from prison, Johnson was handed an ID, documents outlining his criminal case history, $40 and two bus tickets. Having lost all family connections while serving his sentence, Johnson now relies on Fortune Society, a nonprofit that provides housing and services to ex-prisoners in Harlem.

Each day, he navigates the world as best as he can. He involves himself with a local mosque. He practices tai chi and meditates. He attempts to pursue his dream of opening up a shelter for women, though with his lack of credit history securing the funds for such a project has proven close to impossible. He walks the streets of New York, observing people around him. He returns to Fortune Society by 9pm each night, heeding his curfew.

With the current focus on reform, Johnson hopes that re-entry for ex-prisoners, including those having served for decades, will be streamlined to effectively address their needs. Whether freedom can prove liberating, rather than overwhelming, for those convicts who have grayed behind bars, remains to be seen.

For more stories like this, visit www.aljazeera.com/shorts.

Filmmakers Elena Boffetta & Jenna Belhumeur

Article Jenna Belhumeur

Executive Producer Yasir Khan

DSLR Photos Jenna Belhumeur

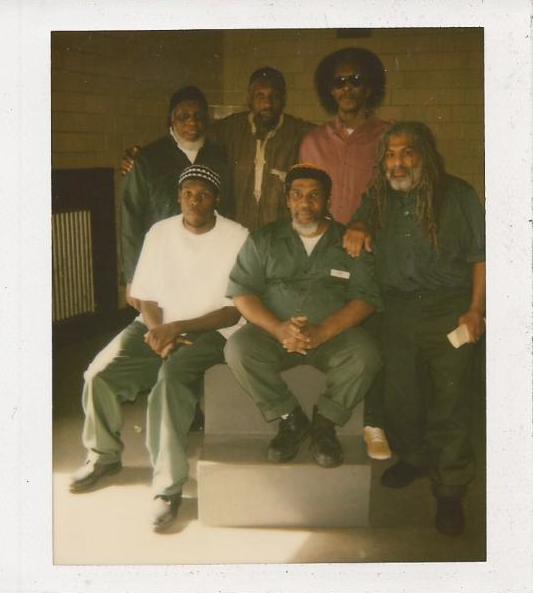

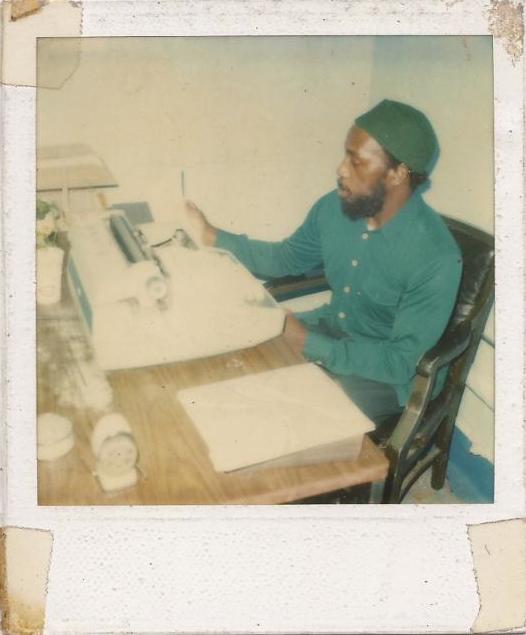

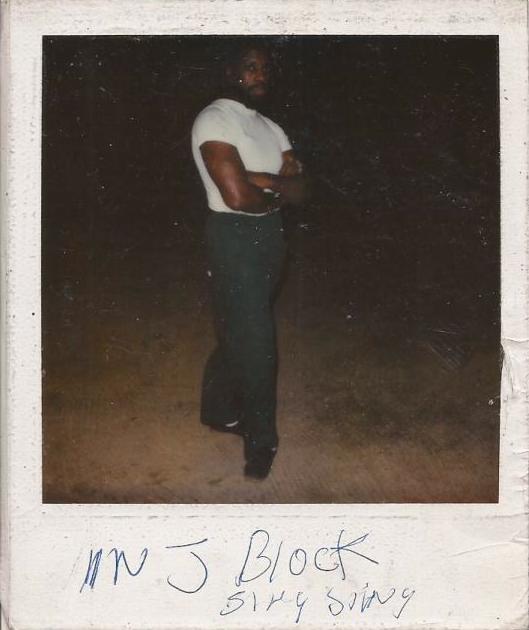

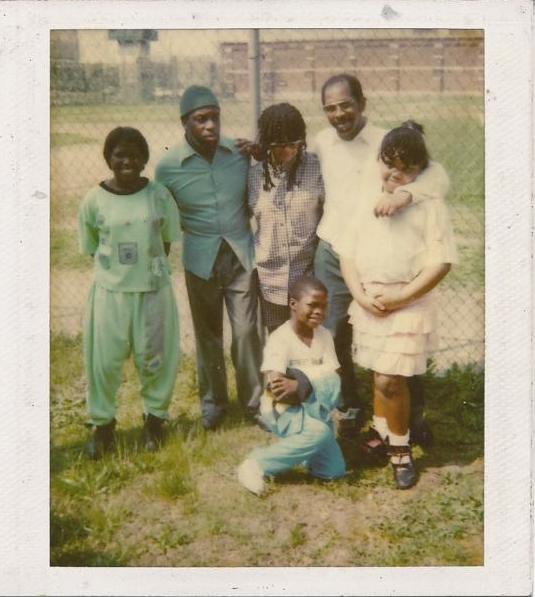

Polaroid Photos Otis Johnson

MY LIFE AFTER

44 YEARS IN PRISON