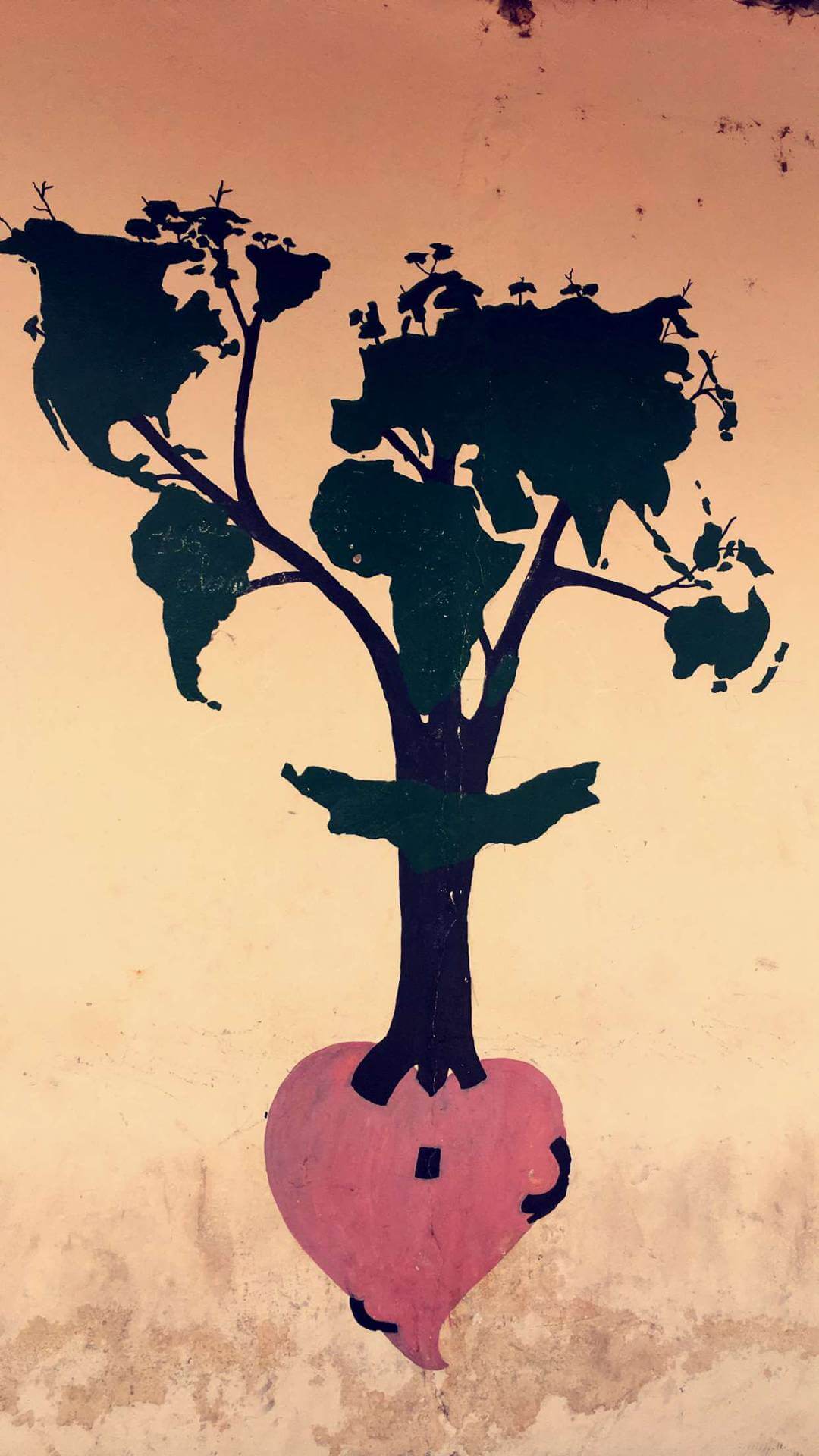

At least 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), or 'cutting'.

It is most prevalent in countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. But it also happens in Europe, the United States and Latin America.

It is a practice carried out by members of different religions and cultures.

But people are fighting back against it.

In Senegal, rappers, activists and members of the communities where it happens are uniting to stop the cutting.

Filmmaker: Fatma Naib

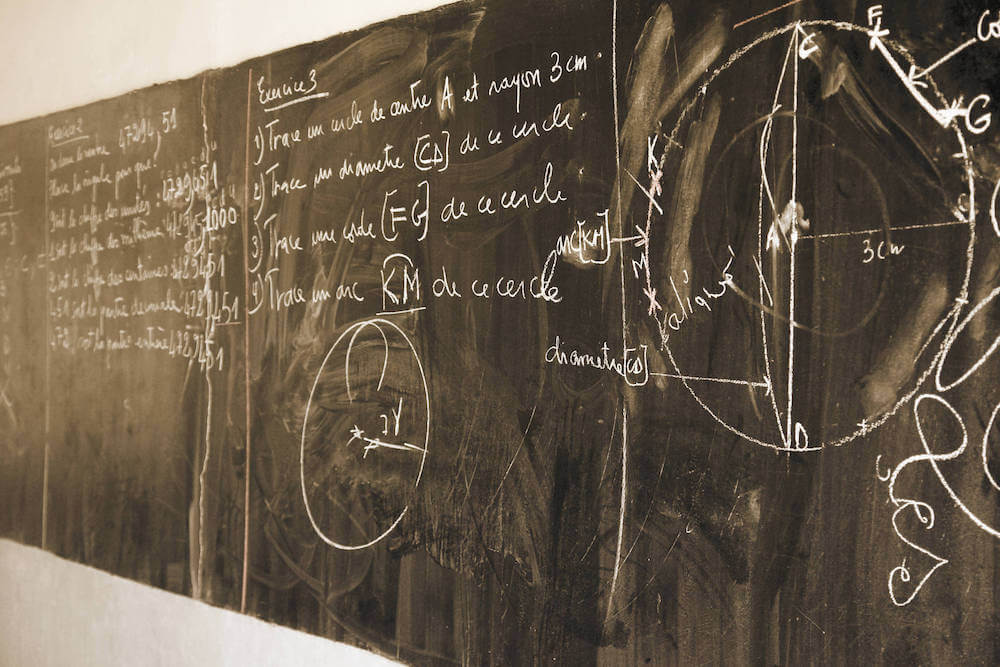

Chapter 1 FGM in Senegal

What is FGM?

FGM, or cutting, as it is also known, is the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia.

The procedure has no health benefits, but can cause great harm and serious health complications for those who undergo the procedure.

Besides causing severe pain, the practice has immediate and long-term consequences for the health of women and girls, including complications during childbirth, which could endanger the lives of both mother and child.

Chapter 2 The ban in Senegal

Chapter 3 The consequences of FGM

Chapter 4 What is being done to end it?

Chapter 5 What does the future hold?

Also read

Waging a lyrical war against FGM

Rapper Sister Fa has helped end the practise in her home village, but her sights are set on the whole of Senegal.

Sudan's midwives take on Female Genital Mutilation

How a school for midwives in eastern Sudan is empowering and educating women and girls about FGM

Magazine: A witness to FGM

Juliana was held down, her mouth covered to smother her screams, as a legally blind woman cut at her genitals.

Fighting female genital mutilation among India's Bohra

FGM: girl-children of Dawoodi Bohra sect are the only Muslim women in India systematically and forcefully mutilated.

Senegal's anti-FGM campaigner: 'My child won't be cut'

Activists in the W African country raise awareness among children and adults about risks of centuries-old tradition.

Memories of FGM: 'I was screaming in pain and fear'

Assita Kanko, a politician in Brussels, recalls when she underwent female genital mutilation as a child in Burkina Faso.

Also Watch

Female genital mutilation continues in Senegal

The UN says 3 million girls had their genitals mutilated last year in Africa alone.

The Race To End Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Ethiopian women are fighting to end female genital mutilation (FGM). Shot by Jay Court in Ethiopia.

Fighting the cut - The Stream

How can the ban on female genital cutting be enforced in the UK and US?

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Survivor Tells Her Story

Breaking the culture of silence around female genital cutting: A survivor's story by Maryum Saifee on International Women's Day

Kenyan girls affected by FGM despite government ban

In Kenya, female genital mutilation, also known as FGM, is illegal practice.

Everywoman- Female Genital Mutilation

This the fifth year marking International Day against Female Genital Mutilation and the UN has launched a multi-million dollar program to reduce the practice by 40% over the next seven years.