Banished:Why menstruation can mean exile

Believed to be impure, some menstruating women in Nepal are forced from their homes - with sometimes deadly consequences.

Untouchable

A small village in far west Nepal. Sabrita Bogati prepares her bed for the next few nights. It’s going to be cold—the 30-year-old has been banished from her house for five days.

Why?

Why do women in the 21st century still follow these strict rules? Do they do it of their own free will? Are they forced? Pema Lhaki (r) from NFCC International seeks answers to these questions. She has been fighting the taboos around menstruation in her country for more than 10 years.

Religious origins

Chhaupadi does have religious origins. It is connected to the Hindu principle of ritual purity. Women are said to lose this purity during menstruation, possibly because religious leaders had no other way to explain the monthly flow of blood. They considered it a threat and as something supernatural, so declared menstruating women impure and ordered them to keep their distance from society.

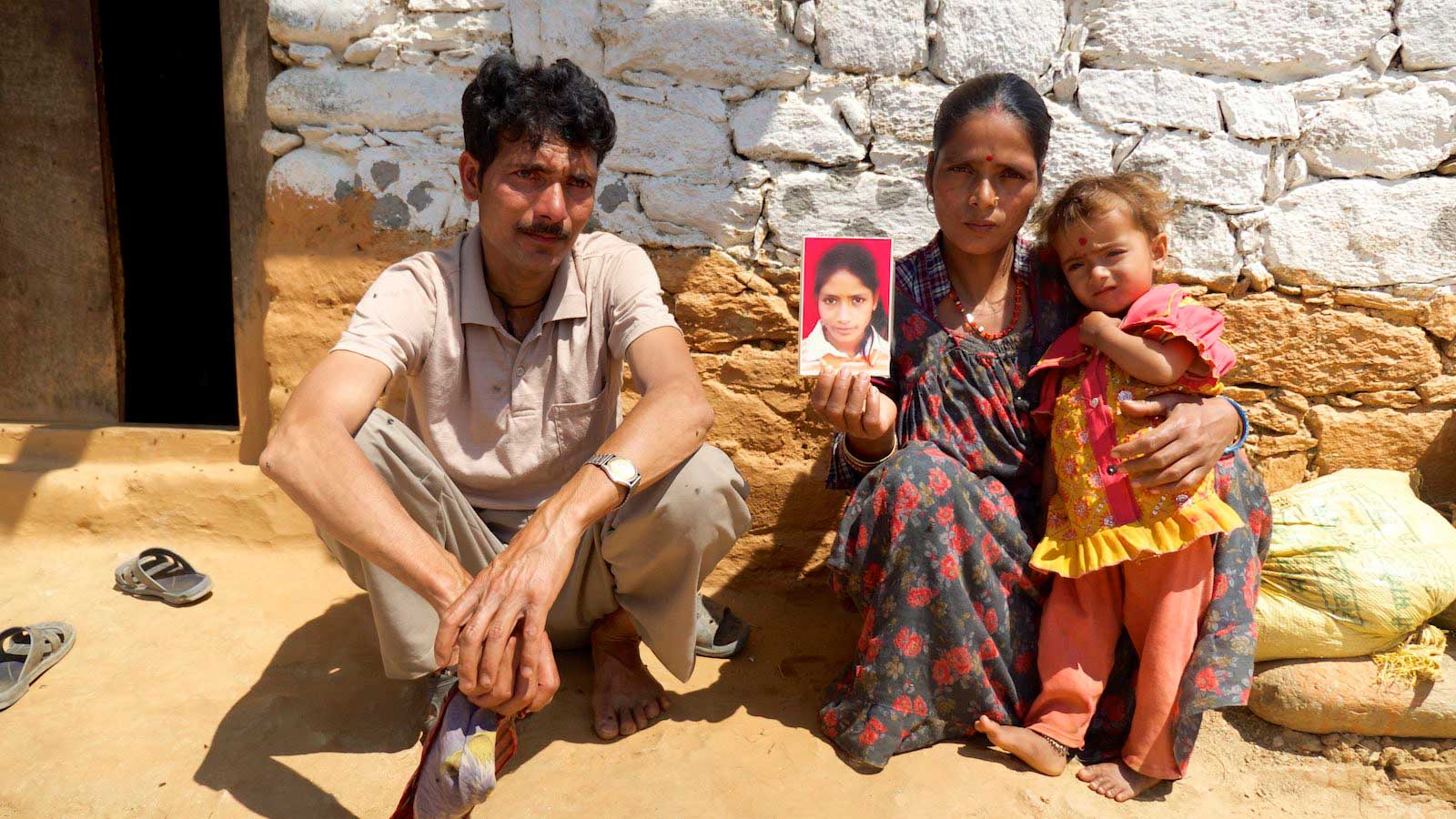

Death in the hut

This fear cost Samila Bhul her life. Her parents still grieve for their eldest daughter, who died two years ago.

Is there any way out?

Sarmila Bhul’s case isn’t just an unfortunate exception. Local newspapers regularly report on incidents related to Chhaupadi. Women who freeze to death, get bitten by snakes or are raped in their huts - another reason why the tradition was banned in 2006. The government has been trying to improve the plight of such women since then.

Purification

Until then, Sabrita has to obey the traditions. It’s day four of her period. Tomorrow morning she will go through the monthly ritual to regain purity.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)